Automated decision-making and profiling under GDPR

Explore the comprehensive framework of GDPR regulations governing automated decision-making and profiling, including practical compliance strategies, real-world examples, and future challenges for businesses in the AI era.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Automated Decision-Making (ADM) and profiling within the framework of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). It aims to clarify the intricate legal definitions, delineate the rights and obligations of data subjects and controllers, and highlight the inherent risks associated with these advanced data processing techniques. While ADM and profiling offer significant benefits in terms of efficiency and consistency across various sectors, their deployment necessitates stringent adherence to GDPR principles to mitigate substantial legal, financial, and reputational exposures. The report underscores the critical importance of transparency, meaningful human intervention, robust data protection impact assessments, and continuous algorithmic auditing as cornerstones of a proactive and compliant data governance strategy.

II. Introduction to Automated Decision-Making and Profiling under GDPR

The increasing reliance on data-driven technologies has brought automated decision-making and profiling to the forefront of data protection discussions. Under the GDPR, these concepts are specifically defined and regulated to safeguard individual rights and freedoms. Understanding their precise definitions, distinctions, and interrelations is fundamental to navigating the complex compliance landscape.

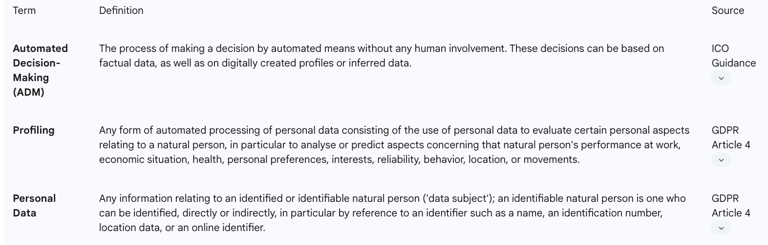

Defining Automated Decision-Making (ADM)

Automated decision-making is precisely defined as the process of making a decision by automated means without any human involvement. These decisions can be based on factual data provided directly by individuals, as well as on digitally created profiles or inferred data derived from other information. Essentially, it signifies a decision reached exclusively by software or a machine, where no human reviews or influences the outcome before it is delivered.

Common examples illustrating ADM include the automated processing of online loan applications that yield immediate approval or denial decisions. Similarly, recruitment processes often employ ADM through aptitude tests that utilize pre-programmed algorithms and criteria to filter or make decisions about candidates. Another straightforward instance is an automated system marking multiple-choice examination answer sheets based on pre-programmed correct answers and grading criteria.

A critical aspect of ADM under GDPR is the interpretation of "solely automated." While the core definition emphasizes the absence of human involvement, a deeper examination reveals a crucial nuance. Article 22 of the GDPR, which governs such decisions, applies only when a decision is "based solely on automated processing". This is not a blanket prohibition on all automated systems. Controllers are explicitly prevented from circumventing these provisions by merely fabricating human involvement. For human oversight to be considered genuine and effective, it must be "meaningful," implying that the individual providing the oversight possesses the "authority and competence to change the decision" and actively "consider[s] all the available input and output data". If a human genuinely "weighs up and interprets the result of an automated decision before applying it to the individual," the process is not deemed solely automated. This distinction is paramount for compliance, as it demands substantive human intervention, not just a perfunctory sign-off. The potential for "automation bias," where human reviewers may unduly favor suggestions from automated systems even when contradictory information exists , further complicates this. Therefore, effective human oversight requires not only the requisite authority and competence but also specific training designed to counteract such biases and encourage critical evaluation of algorithmic outputs.

Defining Profiling

Profiling is broadly defined as "any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person". Its particular purpose is to analyze or predict aspects concerning that natural person's performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behavior, location, or movements. This process involves gathering information about an individual or a group to evaluate their characteristics or behavior patterns, often with the aim of categorization or prediction.

Organizations engage in profiling to discover individuals' preferences, predict their behavior, and/or make decisions about them. This is typically achieved by collecting and analyzing personal data on a large scale, employing algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI), or machine learning to identify associations, build links between different behaviors and attributes, and subsequently create profiles. The data sources for profiling are extensive, encompassing internet searches, buying habits, lifestyle, and behavioral data gleaned from mobile phones, social networks, video surveillance systems, and the Internet of Things (IoT).

A significant, yet often underappreciated, aspect of profiling is that it does not merely process existing data; it actively generates new personal data. The resulting profile, often based on inferences, constitutes "new personal data about that individual". This derived information is fully subject to all GDPR principles, including those pertaining to accuracy, data minimization, and data subject rights. Consequently, organizations must manage the entire lifecycle of this newly generated data with the same rigorous adherence to privacy principles as they would for directly collected information, particularly considering its potential for inherent bias and inaccuracy. Furthermore, a core risk of profiling is its frequent invisibility to individuals, coupled with a lack of understanding regarding how the process works or how it might affect them. This inherent opacity, particularly with complex AI and machine learning algorithms, directly challenges the GDPR's transparency principle and the data subject's right to explanation. Compliance efforts must therefore extend beyond mere disclosure, requiring proactive measures to render profiling understandable and its effects predictable for data subjects, potentially through user-friendly interfaces or simplified explanations.

Distinction and Interrelation between ADM and Profiling

While often discussed together, automated decision-making and profiling are distinct concepts with a significant interrelation. Profiling is a specific form of automated processing and frequently serves as a component of an automated decision-making process. However, it is crucial to recognize that not all profiling activities necessarily lead to an automated decision, and conversely, not all automated decisions involve profiling. For instance, an automated system solely responsible for marking exam sheets constitutes ADM but does not involve profiling. Conversely, categorizing customers by age and gender for purely statistical purposes is profiling, but it may not result in an automated decision with legal or similarly significant effects.

Despite Article 22 specifically targeting solely automated decisions that produce legal or similarly significant effects, it is imperative to understand that profiling activities, even if they do not meet this strict threshold, remain subject to broader GDPR obligations. For example, a data protection authority (DPA) imposed a €1 million fine on EDP Comercializadora for insufficient transparency regarding its profiling activities for marketing purposes, even though these activities were determined not to fall under the strictures of Article 22. The DPA's decision in that case referenced Article 13 (transparency) and Recital 60, underscoring that general data protection principles apply broadly to all profiling activities, regardless of their immediate impact or whether they culminate in an automated decision. Organizations cannot assume exemption from GDPR scrutiny simply because their profiling does not trigger Article 22.

Benefits of ADM and Profiling

Profiling and automated decision-making offer substantial benefits to organizations across various sectors. They can lead to "quicker and more consistent decisions," which is particularly advantageous when analyzing and acting upon very large volumes of data rapidly. Beyond efficiency, these technologies can contribute to "fairer and more accurate decisions" by potentially reducing human biases, as AI systems are capable of avoiding the "typical fallacies of human psychology" and can be subjected to rigorous controls.

These techniques prove useful in diverse fields, including healthcare, education, financial services, and marketing. In the financial sector, for instance, profiling can be instrumental in consumer protection and ensuring compliance with stringent regulatory requirements, such as Anti-Money Laundering (AML) directives.

However, the perceived benefits of efficiency and fairness are inherently conditional and must be approached with caution. While these techniques are touted for their utility, the same sources that highlight their advantages also caution against "potential risks," such as profiling being "often invisible to individuals" and leading to "significant adverse effects". There is also the risk that profiling can "perpetuate existing stereotypes and social segregation". This inherent tension reveals that the very tools designed for efficiency and perceived impartiality can, without appropriate safeguards, inadvertently introduce new, systemic forms of discrimination and harm. Consequently, organizations must approach the deployment of ADM and profiling with a clear understanding that their benefits are contingent upon robust ethical and legal frameworks. The "balancing exercise" between utility and risk is not a one-time assessment but an ongoing commitment to responsible innovation and human-centric design.

Table: Key Definitions (ADM, Profiling, Personal Data)

III. The Core Legal Framework: GDPR Article 22

Article 22 of the GDPR is the cornerstone provision governing automated individual decision-making, including profiling. It establishes a fundamental right for data subjects and sets clear boundaries for organizations utilizing these technologies.

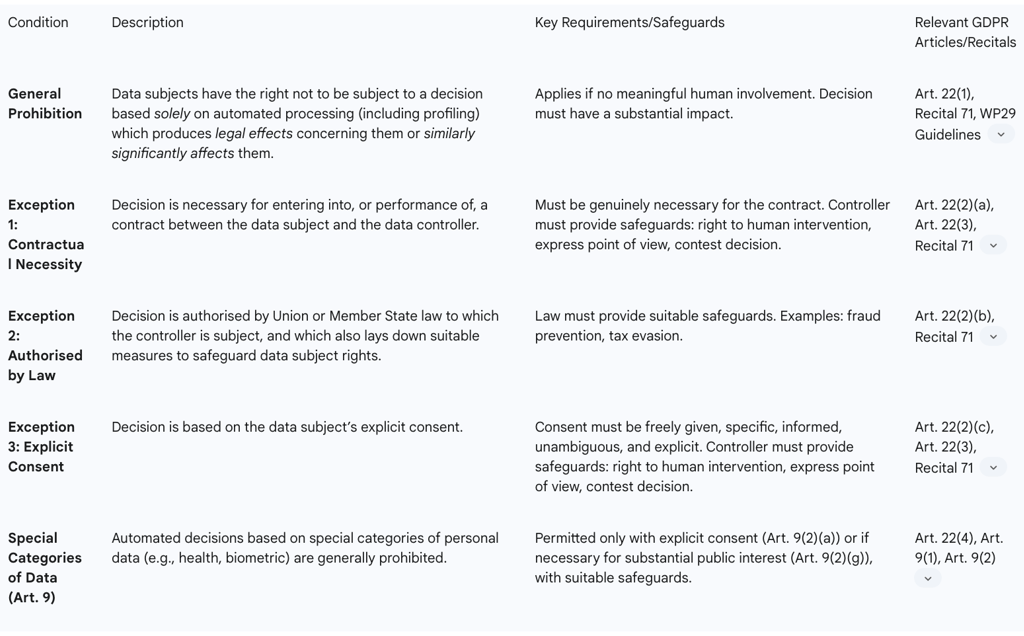

General Prohibition: The Right Not to Be Subject to Solely Automated Decisions

The core principle enshrined in Article 22(1) is that a data subject has the right "not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her". This provision serves as a critical safeguard, ensuring that decisions with substantial impact on individuals are not made without due human consideration and oversight. It is important to note that this is a "qualified right," meaning it is not an absolute prohibition on all automated decisions. Instead, it specifically targets those decisions that are solely automated AND have "legal or similarly significant effects". This qualification is crucial for understanding the precise scope of Article 22, as many automated processes might not fall under this strict definition. Organizations must therefore conduct a careful assessment to determine if their automated processes meet both criteria ("solely automated" and "legal or similarly significant effect") before concluding that Article 22 applies, a process that requires nuanced legal interpretation.

Understanding "Solely Automated"

For a decision to be considered "solely automated" under Article 22, it must be made exclusively by technological means, entirely without meaningful human involvement. The GDPR and accompanying guidance emphasize that controllers cannot circumvent these provisions by merely creating the appearance of human involvement; any oversight must be genuinely "meaningful," not a "token gesture". This means the human reviewer must possess the "authority and competence to change the decision" and actively "consider all the available input and output data". For example, if an HR manager reviews data flagged by an automated clocking-in system before issuing a warning, the decision is not considered solely automated. Similarly, if a recruitment platform filters CVs by software but a human manager then reads the shortlist and makes the interview decisions, it is not solely automated.

The interpretation of "solely automated" has been further clarified by significant case law. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) judgment in case C-634/21, known as "SCHUFA," established that an automated decision can still be considered "solely automated" even if an AI system generates only a "probability value" that is then transmitted by the controller to a third party. This implies that if the human recipient of the automated output merely rubber-stamps it, or if their decision is heavily influenced by the automated recommendation to the extent that their intervention lacks genuine discretion, the decision may still be deemed "solely automated." This ruling significantly broadens the interpretation of "solely automated," placing a higher burden on organizations to demonstrate genuine human oversight, especially when automated systems provide strong recommendations or scores that are subsequently acted upon, challenging the simplistic notion that merely having a human in the loop is sufficient.

Defining "Legal or Similarly Significant Effects"

The applicability of Article 22 hinges on whether the automated decision produces "legal effects" or "similarly significantly affects" the data subject.

A legal effect is one that directly impacts an individual's legal rights or legal status. Examples include decisions affecting fundamental rights like freedom of association, the right to vote, or the ability to take legal action. It also encompasses changes to a person's legal status or their rights under a contract, such as the termination of an agreement, the denial of statutory social benefits (e.g., housing or child benefit), or the refusal of entry into a country or citizenship.

A similarly significant effect is more broadly defined as an impact that is equivalent in its importance to a legal effect, profoundly affecting an individual's circumstances, behavior, or choices. The effects of such processing must be "great or important enough" to warrant the protections of Article 22. Common examples include the automatic refusal of an online credit application or e-recruiting practices that filter out candidates without any human intervention. Decisions that significantly affect an individual's financial circumstances (such as eligibility for credit), access to health services, employment opportunities (e.g., denial of a job or placing someone at a serious disadvantage), or access to education (e.g., university admissions) also fall under this category. Furthermore, automated decision-making that results in differential pricing based on personal data or characteristics could have a significant effect if, for example, prohibitively high prices effectively bar someone from certain goods or services. The inclusion of "similarly significant effects" is crucial because it extends GDPR protection beyond formal legal changes, capturing real-world impacts that, while not altering legal status, can profoundly affect an individual's life, such as financial stability or access to essential services. This significantly broadens the scope of Article 22, requiring organizations to conduct thorough risk assessments, such as Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs), to identify all potential "similarly significant effects" of their automated systems, not just those with explicit legal consequences. This demands a deep understanding of the individual's context and potential vulnerabilities.

Exceptions to the Prohibition

Article 22(1)'s general prohibition on solely automated decisions with legal or similarly significant effects is not absolute. Paragraph 2 outlines three specific exceptions under which such processing is permitted, provided suitable safeguards are in place.

Contractual Necessity: The decision is "necessary for entering into, or performance of, a contract between the data subject and a data controller". This exception is particularly relevant for high-volume, routine transactions, such as instant online loan approvals or automated credit card payment processing, where manual human intervention would be impractical. However, the processing must be genuinely

necessary for the contract's performance, not merely mentioned in the contract as a condition. Organizations should always consider whether a less privacy-intrusive method could achieve the same contractual objective.

Authorised by Union or Member State Law: The decision is "authorised by Union or Member State law to which the controller is subject and which also lays down suitable measures to safeguard the data subject’s rights, freedoms and legitimate interests". This exception often applies to automated processes required by law for purposes such as fraud prevention, tax evasion monitoring, or ensuring the security and reliability of services.

Explicit Consent: The decision is "based on the individual's explicit consent". Explicit consent provides a higher level of individual control over personal data, deemed appropriate given the serious privacy risks associated with such automated processing. For consent to be valid under GDPR, it must be "freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous". Organizations must provide clear and detailed information about the decision-making process, its consequences, and the logic involved. Consent must be "sufficiently clear and comprehensive," "granular" for different processing purposes, and new consent must be sought if the processing purpose changes. However, organizations must be wary of "consent fatigue," where individuals become overwhelmed by requests and may not fully understand the implications of their consent.

Crucially, even when one of these exceptions applies, organizations are still obligated to implement "suitable measures to safeguard the data subject’s rights, freedoms and legitimate interests". These safeguards must, at a minimum, include the data subject's right to obtain human intervention, to express their point of view, and to contest the decision. This underscores that the exceptions do not negate the fundamental need for robust data subject rights and oversight. Compliance, therefore, is not merely about fitting into an exception but about implementing a comprehensive framework of rights and safeguards around that exception.

Special Categories of Personal Data (Sensitive Data)

The GDPR imposes heightened restrictions on the processing of "special categories of personal data," often referred to as sensitive data. These include data revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, genetic data, biometric data processed for unique identification, data concerning health, and data concerning a person's sex life or sexual orientation.

Automated processing of these special categories of personal data is generally prohibited unless specific conditions from Article 9(2) apply. For such processing to be lawful, it typically requires either the data subject's explicit consent for one or more specified purposes, or that the processing is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, based on Union or Member State law that provides suitable and specific safeguards.

A particularly complex aspect arises when profiling activities infer sensitive data from seemingly non-sensitive information. For example, analysis of location data or call logs could potentially infer an individual's socioeconomic status or even health conditions. If such inferred data falls under special categories, the stricter rules of Article 9(2) apply. The Digital Services Act (DSA), for instance, specifically restricts advertising based on profiling that uses special categories of personal data. This means organizations must not only identify direct collection of special category data but also diligently assess whether their profiling activities, through inference, generate or utilize such data. If they do, the higher bar of explicit consent or substantial public interest applies, along with enhanced safeguards. This presents a significant compliance challenge for AI systems capable of deriving sensitive insights from seemingly innocuous data.

IV. Safeguards and Compliance Requirements

Effective compliance with GDPR regarding automated decision-making and profiling extends beyond merely identifying applicable legal bases and exceptions. It necessitates the implementation of robust safeguards and adherence to fundamental data protection principles throughout the entire data processing lifecycle.

Transparency and Information Obligations

A cornerstone of GDPR compliance is transparency. Organizations are mandated to provide individuals with "meaningful information about the logic involved" in automated decisions, as well as the "significance and envisaged consequences" of such processing for them. This obligation extends to informing individuals about any personal data derived from inferences and correlations with other data. Privacy policies and information clauses must be "clear and understandable" to the data subject , moving beyond mere legal jargon. The aim is not just to inform about the decision itself, but to explain the logic underpinning it. For instance, in the context of credit scoring, individuals should be entitled to know the categories of data crucial to the internal scoring model and any circumstances that would invariably lead to a refusal.

A significant ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) reinforces these transparency obligations. In a case concerning automated credit assessment, the CJEU affirmed that data subjects are entitled to receive not just the elements of their personal data used, but also the "procedures and principles actually applied" in the automated decision-making process. The ruling clarified that organizations cannot simply invoke trade secrets to deny this information. While organizations are not required to disclose the proprietary algorithm itself, they must provide a concise, transparent, intelligible, and easily accessible explanation that allows the data subject to understand which of their personal data was used and how it was utilized. This presents a substantial practical challenge, particularly for complex AI and machine learning models, often referred to as "black box" systems, where the internal workings are inherently opaque. Organizations must develop robust governance frameworks to document and explain their ADM logic, potentially through interpretability tools or simplified explanations, moving beyond generic privacy notices to ensure genuine understanding.

Right to Human Intervention, Express Point of View, and Contest the Decision

As a fundamental safeguard, individuals subjected to solely automated decisions with legal or similarly significant effects must be afforded specific rights: the right to "obtain human intervention," to "express their point of view," and to "contest the decision". This means that even when automated decisions are permitted under an exception, a human review mechanism must be in place.

The human intervention must be "meaningful" and not merely a "rubber stamp". The individual conducting the review must have the genuine authority and competence to override or change the automated outcome and must actively consider all available information, not just blindly accept the algorithm's suggestion. They should also document their reasons for agreeing or disagreeing with the algorithm. Operationalizing meaningful human intervention at scale presents a significant challenge, especially for high-volume processes like online loan applications or automated recruitment screenings. Organizations need to design their systems with "human-in-the-loop" mechanisms that are genuinely effective and scalable, which may involve tiered review processes, clear escalation paths, and sufficient staffing with appropriately trained personnel.

Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs)

The GDPR mandates that a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) be conducted whenever a data processing activity is "likely to result in a high risk to individuals' rights and freedoms". Automated decision-making and profiling, particularly when they involve large-scale processing, sensitive data, or have significant effects on individuals, almost invariably fall into this high-risk category. The DPIA serves as a proactive risk management tool, enabling organizations to identify, assess, and mitigate potential non-compliance risks before deploying new systems or processes. Its requirement aligns with the principles of privacy by design and privacy by default , compelling organizations to integrate data protection considerations from the earliest stages of system development. Organizations should integrate DPIAs early in the development and deployment of any ADM or profiling system to proactively identify and mitigate risks, rather than treating it as a post-hoc compliance exercise.

Data Minimization and Purpose Limitation

Fundamental to all data processing under GDPR are the principles of data minimization and purpose limitation. Data minimization dictates that organizations should collect only the minimum amount of personal data that is necessary and proportionate for the specific purpose of processing. Purpose limitation requires that data collected for one specified, explicit, and legitimate purpose should not be repurposed for unrelated automated decision-making without obtaining further consent from the individual or establishing another compatible legal basis.

These principles can create an inherent tension with the operational demands of AI and machine learning models, which often perform better with larger and more diverse datasets. The temptation to collect and retain more data than strictly necessary for a stated purpose is a significant compliance risk, as it increases the potential for "reidentification attacks" if data minimization is not rigorously applied. Organizations deploying AI for ADM must carefully balance the technical desire for extensive data with legal requirements, potentially necessitating the use of advanced privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) like pseudonymization or differential privacy, alongside rigorous data governance to ensure data is used only for compatible purposes.

Accuracy and Bias Prevention

The accuracy of personal data is paramount in profiling and automated decision-making, as any inaccuracy in the dataset will inevitably lead to flawed results and potentially unfair or discriminatory decisions. Organizations are therefore obligated to implement robust measures to verify and ensure the accuracy of their datasets on an ongoing basis.

Beyond mere factual accuracy, there is a critical need for bias prevention. Algorithms, if not carefully designed and trained, can perpetuate or even amplify existing stereotypes and social segregation present in the training data. This can lead to discriminatory practices and significant adverse effects for individuals. Organizations must take proactive steps to prevent errors, bias, and discrimination in their ADM and profiling systems. This includes rigorous review of algorithms and the underlying datasets for hidden biases. The need to prevent hidden bias and ensure appropriate statistical techniques strongly implies the necessity of algorithmic auditing. Best practices recommended by authorities include regular quality assurance checks, algorithmic auditing, providing information for independent auditing, and contractual assurances for third-party algorithms. Organizations should implement regular, independent algorithmic audits to proactively identify and mitigate biases and inaccuracies in their ADM and profiling systems, extending beyond traditional data security audits to encompass specialized expertise in algorithmic fairness.

Security Measures

Given the often large-scale processing of personal data and the potential for significant impacts, robust security measures are essential for ADM and profiling systems. Organizations must implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure a level of security commensurate with the risk, including encryption, two-factor authentication, and regular vulnerability assessments. This is crucial for protecting personal data against unauthorized access, data breaches, and cyber threats. The risk of data breaches is amplified when large datasets are involved in ADM and profiling. Therefore, organizations must ensure their security measures are particularly stringent and continuously updated to match the heightened risks posed by these activities, potentially requiring advanced cybersecurity frameworks.

Accountability

The GDPR's principle of accountability requires organizations not only to comply with the regulation but also to be able to demonstrate that compliance. For ADM and profiling, this means being able to show that necessary safeguards have been implemented and that steps have been taken to protect individuals' rights. This necessitates comprehensive documentation of procedures, decisions, and the safeguards in place throughout the entire ADM lifecycle. This includes record-keeping of the characteristics of datasets used, reasons for their selection, and documentation of training techniques for AI systems. Proving compliance is particularly challenging for complex ADM systems where the underlying logic might be opaque. Therefore, comprehensive documentation, from data collection and model training to decision-making processes and human oversight, is crucial for demonstrating accountability to regulatory authorities.

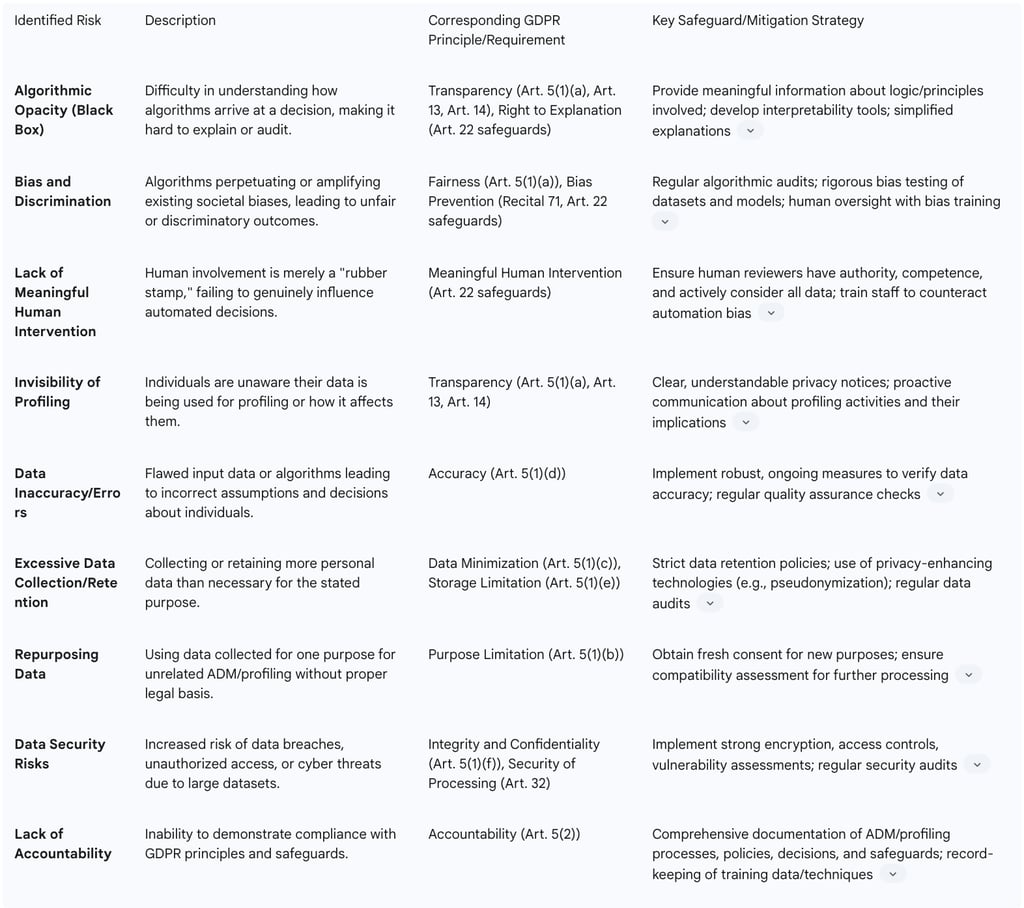

Table: Risks and Safeguards in ADM/Profiling

V. Real-World Applications and Case Studies

Automated decision-making and profiling are increasingly pervasive across diverse sectors, each presenting unique opportunities and compliance challenges under the GDPR. Examining real-world applications and notable case studies provides practical insights into the implications of these technologies.

Examples across various sectors:

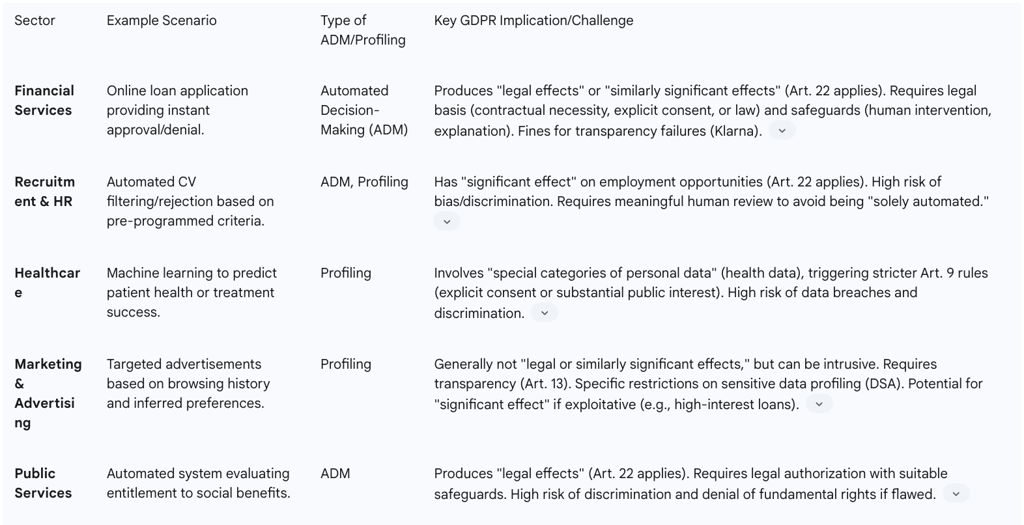

Financial Services (Loans, Credit Scoring, Fraud Detection)

Examples: Financial institutions frequently employ ADM for online loan applications, credit scoring, and fraud detection. This can also extend to differential pricing, where automated systems adjust prices based on an individual's profile.

Implications: These applications carry a high risk due to their potential for "legal effects" or "similarly significant effects" on individuals' financial circumstances, such as denying a loan or imposing prohibitively high prices. Compliance requires strict adherence to Article 22, demanding transparency about the logic involved and ensuring the right to human intervention. The Swedish DPA fined Klarna Bank AB for failing to provide meaningful information about the rationale and foreseeable consequences of its automated credit decisions, underscoring the importance of transparency even when Article 22 is not directly invoked for the decision's outcome.

Recruitment and HR (Aptitude Tests, CV Filtering)

Examples: Many organizations utilize ADM in recruitment, such as automated aptitude tests or systems that filter and reject CVs based purely on keywords or pre-programmed criteria.

Implications: Decisions in recruitment can have a "significant effect" on an individual's employment opportunities. These systems carry a notable risk of discrimination and bias if algorithms are not carefully designed and monitored. To avoid being classified as "solely automated" under Article 22, and thus subject to its strict conditions, these processes require meaningful human review where a human has the authority and competence to override the automated outcome.

Healthcare (Medical Treatments, Patient Health Prediction)

Examples: Profiling is increasingly used in medical treatments, where machine learning is applied to predict patients' health outcomes or the likelihood of a treatment's success based on group characteristics.

Implications: Processing in healthcare invariably involves "special categories of personal data," specifically health data. This triggers stricter GDPR rules, requiring either explicit consent from the individual or a demonstration that processing is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, along with suitable safeguards. The deployment of ADM and profiling in healthcare presents a complex challenge: while it offers immense benefits in efficiency and personalized care, it also poses the highest risks due to the sensitivity of health data. The GDPR's stringent requirements for special categories of data mean that the legal basis and safeguards must be exceptionally robust. Historical incidents, such as the WannaCry ransomware attack on the UK's NHS , highlight the severe real-world consequences of technological vulnerabilities and inadequate IT systems in this sector. Therefore, organizations in healthcare must prioritize privacy-by-design, robust security measures, and clear ethical frameworks when deploying ADM and profiling, ensuring that the pursuit of innovation does not compromise fundamental rights.

Marketing and Advertising (Targeted Ads, Personalised Content)

Examples: Profiling is widely used in marketing and advertising for targeted advertisements based on browsing history, personal preferences, and demographics. This also includes recommender systems that suggest content like music or videos based on user behavior.

Implications: While targeted advertising generally does not produce "legal or similarly significant effects" that would trigger Article 22 , it can still be highly intrusive and requires clear transparency. The Spanish DPA fined EDP Comercializadora €1 million for insufficient information about its profiling practices for marketing purposes, even though the profiling did not meet the Article 22 threshold. This demonstrates that general GDPR principles, particularly transparency (Article 13), apply broadly to all profiling activities. Furthermore, the Digital Services Act (DSA) imposes specific restrictions on presenting advertisements based on profiling using special categories of personal data. Organizations in marketing should not assume blanket exemption from Article 22. They must carefully assess the potential impact of their profiling, especially on vulnerable individuals, or if the targeting leads to exploitative outcomes (e.g., targeting high-interest loans to those in financial difficulty, which could lead to further indebtedness ), as such scenarios could elevate the profiling to a "similarly significant effect."

Public Services (Social Benefits, Law Enforcement)

Examples: Public sector bodies may use ADM to evaluate an individual's entitlement to social benefits (e.g., child or housing benefit) or for fraud detection in social benefit claims. Profiling is also utilized in law enforcement contexts.

Implications: Decisions in public services often produce "legal effects" and are inherently high-risk, particularly concerning fundamental rights. These applications carry a significant risk of discrimination if not implemented with extreme care. A notable case involved the Dutch DPA finding that an algorithmic system used by the government to automatically detect fraud in social benefits requests breached the principle of fairness due to its discriminatory nature. Such processing typically requires specific legal authorization that also lays down suitable safeguards for data subjects. The use of ADM in public services, while potentially justified by "substantial public interest," carries a high risk of systemic discrimination and denial of fundamental rights. This highlights a critical tension between state efficiency and security and individual freedoms. Public sector bodies deploying ADM must implement exceptionally robust safeguards, including independent oversight, rigorous bias testing, and clear mechanisms for redress, to ensure that public interest justifications do not erode individual rights.

Challenges in Implementation

Implementing GDPR-compliant automated decision-making and profiling systems presents several interconnected challenges for organizations:

Opacity of Algorithms (Black Box Problem): Many advanced AI and machine learning algorithms are inherently complex and opaque, making it difficult to understand how they arrive at specific decisions. This "black box" nature complicates the ability to provide meaningful explanations to data subjects and conduct thorough audits.

Risk of Hidden Bias and Perpetuating Stereotypes: Algorithms are trained on data, and if this data contains historical or societal biases, the algorithms can learn and perpetuate these biases, leading to discriminatory outcomes. Identifying and mitigating these "hidden biases" is a significant technical and ethical challenge.

Difficulty in Defining "Meaningful Human Intervention": While the GDPR mandates meaningful human intervention for certain ADM, precisely defining what constitutes "meaningful" in practice, especially in complex scenarios, remains a challenge. It requires careful consideration of authority, competence, and genuine engagement with the automated output.

Invisibility of Profiling to Individuals: Profiling often occurs without individuals' explicit awareness or understanding of how their personal information is being used to create profiles and influence decisions about them. This lack of visibility undermines transparency and individual control.

Ensuring Data Accuracy and Preventing Errors: The effectiveness and fairness of ADM and profiling heavily rely on the accuracy of the underlying data. Inaccuracies can lead to flawed results and negative consequences for individuals. Maintaining ongoing data accuracy, especially with large, dynamic datasets, is a continuous challenge.

Balancing Data Minimization with AI/ML Data Needs: AI and machine learning models often benefit from vast amounts of data for optimal performance. This creates a tension with the GDPR's principle of data minimization, which requires limiting data collection to what is necessary and proportionate.

Technological Vulnerabilities and Infrastructure Weaknesses: The increasing integration of digital tools and AI systems amplifies the risk of data breaches and unauthorized access, particularly if underlying IT infrastructures are outdated or lack sufficient cybersecurity protocols.

Many of these challenges are interconnected. For example, algorithmic opacity makes it harder to identify hidden bias, which in turn complicates providing meaningful explanations and ensuring effective human intervention. These factors collectively contribute to the "invisibility" of profiling. Addressing these challenges therefore requires a holistic approach, combining legal, technical, and organizational measures, rather than attempting to tackle them in isolation.

Table: Real-World Examples of ADM/Profiling and GDPR Implications

VI. Enforcement and Consequences of Non-Compliance

The GDPR is enforced by independent supervisory authorities in each EU Member State, such as the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) in the UK and the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) at the EU level. These authorities are empowered to handle complaints, investigate compliance, and issue a range of penalties for established violations. The EDPB, which succeeded the Article 29 Working Party (WP29), plays a crucial role in issuing guidelines that interpret GDPR provisions, including those on ADM and profiling.

Regulatory Bodies and Guidelines

The primary regulatory bodies overseeing GDPR compliance are the national Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) in each EU Member State and the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) in the UK. At the European level, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) provides overarching guidance and ensures consistent application of the GDPR across the Union. The EDPB has endorsed key guidelines, including those on Automated Individual Decision-Making and Profiling, originally developed by the Article 29 Working Party (WP29).

The regulatory landscape is continuously evolving. The EU AI Act, which entered into force in August 2024 with obligations taking effect from February 2025, introduces a risk-based framework for AI systems, some of which directly relate to ADM and profiling. Similarly, the Digital Services Act (DSA), in force since February 2024, imposes specific restrictions on certain uses of profiling, particularly concerning online advertising. In the UK, GDPR guidance is currently under review due to the Data (Use and Access) Act, which came into law in June 2025. This dynamic and evolving regulatory environment, encompassing not only the core GDPR but also sector-specific and AI-specific legislation, means that organizations operating in the EU/UK must stay abreast of these additional layers of compliance requirements for their automated systems.

Financial Penalties and Fines

Non-compliance with GDPR provisions can result in severe financial penalties. The GDPR specifies two tiers of administrative fines:

Tier 1: Up to €10 million or 2% of the organization's total worldwide annual turnover from the preceding financial year, whichever is higher, typically for less severe infractions or first-time violations.

Tier 2: Up to €20 million or 4% of the organization's total worldwide annual turnover from the preceding financial year, whichever is higher, generally reserved for more severe or repeat violations.

Several high-profile fines have been levied, demonstrating the significant financial repercussions of non-compliance. Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, has faced multiple substantial fines, including a record €1.2 billion, €405 million, €390 million, and €265 million, often related to issues of consent, transparency, and children's data. Other notable fines include Amazon (€746 million), TikTok (€345 million), LinkedIn (€310 million), and Uber (€290 million).

Specific enforcement actions related to ADM and profiling further illustrate the risks. Klarna Bank AB was fined approximately €750,000 by the Swedish DPA for transparency infringements related to its automated credit application decisions. The Spanish DPA fined EDP Comercializadora €1 million for insufficient information provided to data subjects about its profiling activities for marketing purposes, even though these activities did not fall under the strict Article 22 definition of ADM. A telecommunications company was also fined by the ICO for using profiling to make unwanted marketing calls without consent. These cases demonstrate that fines are imposed not only for discriminatoryoutcomes of ADM but also for failures in process, specifically a lack of transparency and insufficient information about profiling. Compliance efforts must therefore focus equally on procedural aspects—such as transparency, establishing a clear legal basis, and implementing robust safeguards—as on preventing adverse outcomes, as regulators are actively enforcing both.

Reputational Damage and Loss of Trust

Beyond direct financial penalties, GDPR non-compliance can inflict severe and lasting damage to an organization's reputation. Public awareness of privacy rights is at an unprecedented high, making customers, clients, and employees increasingly vigilant about how their personal data is handled. A single data breach or non-compliance incident can trigger extensive negative media coverage, significant social media backlash, and a profound loss of trust, which can have long-term adverse effects on customer loyalty and brand image. High-profile incidents, such as those involving British Airways, serve as stark reminders of how data breaches and GDPR non-compliance can lead to widespread public scrutiny and severe reputational harm. While financial penalties are immediate and quantifiable, the erosion of trust and reputational damage can have more profound and enduring negative impacts on a business, often outweighing the direct financial costs. Organizations should therefore perceive GDPR compliance not merely as a legal obligation to avoid fines but as a strategic imperative for maintaining customer relationships and brand integrity.

Operational Disruptions and Legal Costs

Non-compliance with GDPR can trigger extensive audits and investigations by data protection authorities, which are inherently time-consuming and can significantly disrupt an organization's regular business operations. If non-compliance is established, authorities may impose additional corrective measures, such as temporary or permanent restrictions on data processing, or even order the erasure of personal data, further impeding operational capabilities.

Furthermore, GDPR non-compliance exposes businesses to potential legal challenges, including class-action lawsuits from affected data subjects who can seek compensation for both material and non-material damages resulting from an infringement. Organizations may also incur substantial legal costs associated with defending against regulatory actions or civil suits. These legal battles can be protracted and costly, diverting valuable resources that could otherwise be used for business development. The significant operational overheads (audits, processing bans) and resource drain (legal costs) resulting from non-compliance underscore that robust compliance is a critical component of operational resilience, contributing to business continuity and stability. Investing in proactive GDPR compliance for ADM and profiling can therefore be viewed as a strategic investment in long-term business stability.

Notable Enforcement Actions and Case Law

Recent enforcement actions and court rulings provide crucial insights into regulatory expectations regarding ADM and profiling:

CJEU on Credit Assessment :

A landmark ruling by the CJEU in February 2025, stemming from a case involving automated credit assessment, compelled a data controller to disclose the "procedures and principles actually applied" in its automated decision-making process. The court emphasized the data subject's right to meaningful information about the logic involved, even when faced with claims of trade secrets, reinforcing the transparency obligations under Article 15 and 22 of the GDPR.

Dutch DPA on Social Benefits Fraud :

The Dutch Data Protection Authority found that an algorithmic system used by the government to automatically detect fraud in social benefits requests breached the principle of fairness, deeming the processing "discriminatory." This case highlights the significant risks and potential for systemic discrimination when ADM is deployed in public sector contexts, particularly where it affects fundamental rights like access to social welfare.

Klarna Bank AB :

The Swedish DPA imposed a fine of approximately €750,000 on Klarna for transparency infringements related to its automated credit decisions. Klarna's data protection notice failed to provide meaningful information about the rationale, meaning, and foreseeable consequences of its ADM for credit applications, demonstrating that even if the decision itself is permissible, a lack of transparency in the process can lead to substantial penalties.

EDP Comercializadora :

The Spanish DPA fined this energy company €1 million for not sufficiently informing data subjects about the profiling it engaged in for marketing purposes. This case is significant because the DPA ruled that transparency obligations under Article 13 apply to profiling activities even when they do not meet the strict criteria for Article 22 ADM.

Clubhouse :

The Italian DPA fined the social audio chat app Clubhouse €2 million for multiple GDPR infractions, including a lack of transparency regarding the use of users' personal data and failing to identify an accurate legal basis prior to profiling users and sharing their account information.

The range of these cases, spanning from major tech companies to financial institutions and public sector bodies, and focusing on both the outcomes (e.g., discrimination in social benefits) and the processes (e.g., transparency failures in credit and marketing), indicates that GDPR enforcement is broad, sophisticated, and increasingly focused on the nuances of ADM and profiling. The CJEU ruling further strengthens data subjects' rights in ADM contexts. Organizations, regardless of their size or the perceived criticality of their automated systems, cannot rely on escaping scrutiny. Regulators are actively pursuing violations across various sectors and for diverse aspects of non-compliance.

VII. Conclusion and Recommendations for Compliance

Automated decision-making and profiling technologies offer compelling advantages in efficiency, consistency, and potentially enhanced fairness. However, their deployment under the GDPR is subject to a rigorous legal framework designed to protect individual rights and freedoms. The insights derived from current definitions, legal interpretations, and enforcement actions underscore that compliance is not merely a legal checkbox but a strategic imperative for responsible innovation.

Key Takeaways:

Nuanced Definitions: ADM involves decisions made solely by automated means, requiring meaningful human intervention to avoid the strictures of Article 22. Profiling, while often a component of ADM, is a distinct automated processing activity that generates new personal data and triggers broader GDPR obligations even if it doesn't lead to an Article 22 decision.

Qualified Prohibition: Article 22 prohibits solely automated decisions only if they produce "legal effects" or "similarly significantly affect" individuals. This broad scope extends beyond formal legal changes to encompass real-world impacts on financial circumstances, employment, health, and education.

Conditional Exceptions: While exceptions exist for contractual necessity, legal authorization, or explicit consent, these do not negate the fundamental requirement for robust safeguards, including the data subject's right to human intervention, to express their point of view, and to contest the decision.

Heightened Scrutiny for Sensitive Data: The processing of special categories of personal data, whether directly collected or inferred through profiling, faces stricter conditions, typically requiring explicit consent or substantial public interest.

Significant Risks and Enforcement: Non-compliance carries substantial financial penalties, severe reputational damage, and operational disruptions. Recent enforcement actions demonstrate regulators' focus on transparency, accountability, and the prevention of bias, even for procedural failures.

Actionable Steps for Ensuring GDPR Compliance in ADM and Profiling:

To navigate this complex landscape effectively, organizations should adopt a proactive, multi-faceted approach:

Map and Review Processes: Conduct a thorough audit to identify all existing and planned automated decision-making and profiling activities. Critically assess whether these processes are "solely automated" and if they produce "legal or similarly significant effects" on individuals. This foundational step is crucial for determining the applicability of Article 22.

Conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs): For any ADM or profiling activity deemed likely to result in a high risk to individuals' rights and freedoms, a comprehensive DPIA is mandatory. Integrate DPIAs early in the design and development phases to proactively identify and mitigate risks, rather than as a reactive measure.

Ensure Transparency: Provide clear, concise, and meaningful information to data subjects about the existence of ADM and profiling, the logic involved, the significance, and the envisaged consequences of the processing. This includes explaining how inferred data is used. Organizations must be prepared to explain the "procedures and principles actually applied" in their automated systems, even if it means developing simplified explanations for complex algorithms.

Implement Robust Safeguards: Design systems and processes that genuinely guarantee data subjects' rights to obtain human intervention, express their point of view, and contest automated decisions. Ensure that human reviewers possess the necessary authority and competence to override automated outcomes and are trained to critically evaluate algorithmic suggestions, mitigating automation bias. Document these review procedures meticulously.

Establish a Valid Legal Basis: For all ADM and profiling activities, identify and document a clear and appropriate legal basis under GDPR (e.g., explicit consent, contractual necessity, or legal authorization). When relying on consent, ensure it is freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous.

Prioritize Data Quality: Implement measures to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and currency of personal data used in profiling and ADM systems. Adhere strictly to data minimization principles, collecting only the data necessary and proportionate for the stated purpose. Enforce purpose limitation, ensuring data collected for one purpose is not repurposed for unrelated ADM without a new legal basis.

Mitigate Bias and Discrimination: Proactively implement strategies to prevent errors, bias, and discrimination in algorithmic design and deployment. This includes regular algorithmic audits, rigorous testing of training datasets for inherent biases, and continuous monitoring of system outputs for discriminatory effects.

Strengthen Security: Apply robust technical and organizational security measures commensurate with the risks posed by ADM and profiling activities. This includes encryption, access controls, and regular vulnerability assessments to protect personal data against unauthorized access and breaches.

Maintain Accountability: Document all compliance efforts, policies, procedures, and decisions related to ADM and profiling. This comprehensive record-keeping is essential for demonstrating accountability to supervisory authorities.

Stay Informed: Continuously monitor evolving regulatory guidance from the EDPB, ICO, and other relevant authorities, as well as new legislation such as the EU AI Act and the Digital Services Act, to ensure ongoing compliance in a dynamic legal landscape.

By diligently implementing these recommendations, organizations can harness the benefits of automated decision-making and profiling while upholding the fundamental data protection rights enshrined in the GDPR, thereby building trust and ensuring long-term operational resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Automated Decision-Making (ADM) under GDPR?

Automated Decision-Making (ADM) under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) refers to the process of reaching a decision solely by automated means, meaning without any human involvement. These decisions can be based on factual data provided by individuals or on digitally created profiles and inferred data. For a decision to be considered "solely automated" under Article 22, it must be exclusively made by technology. Crucially, any human oversight must be "meaningful," implying that the individual reviewer has the authority and competence to change the decision and actively considers all available input and output data. Simple "rubber-stamping" of an automated outcome does not constitute meaningful human involvement. Examples include automated processing of online loan applications, aptitude tests in recruitment, or automated marking of multiple-choice exams.

What is 'profiling' in the context of GDPR, and how does it relate to ADM?

Profiling under GDPR is defined as "any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person." Its purpose is to analyse or predict aspects concerning an individual's performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behaviour, location, or movements. Organisations engage in profiling to discover preferences, predict behaviour, and make decisions about individuals, often by analysing large datasets using algorithms or AI.

While often discussed together, ADM and profiling are distinct but interrelated. Profiling is a specific form of automated processing that often serves as a component of an ADM process. However, not all profiling leads to an automated decision with legal or similarly significant effects, and not all automated decisions involve profiling. For instance, an automated exam marking system is ADM but not profiling. Conversely, categorising customers by age for statistical purposes is profiling but may not result in an automated decision. All profiling activities, regardless of whether they lead to an ADM decision under Article 22, are subject to broader GDPR obligations, particularly transparency.

When does GDPR Article 22 apply to automated decisions?

Article 22 of the GDPR applies when a decision is based solely on automated processing, including profiling, and produces legal effects concerning the data subject or similarly significantly affects him or her.

A "legal effect" directly impacts an individual's legal rights or status, such as denying a contract, refusing statutory social benefits, or denying entry into a country. A "similarly significant effect" is an impact equivalent in importance to a legal effect, profoundly affecting an individual's circumstances, behaviour, or choices. Examples include the automatic refusal of an online credit application, e-recruiting practices that filter out candidates without human intervention, or differential pricing that effectively bars someone from goods or services. This provision serves as a critical safeguard against impactful decisions made without human consideration.

Are there any exceptions to the general prohibition under GDPR Article 22?

Yes, the general prohibition on solely automated decisions with legal or similarly significant effects is not absolute. Article 22(2) outlines three exceptions:

Contractual Necessity: The decision is necessary for entering into or performing a contract between the data subject and the data controller (e.g., instant online loan approvals).

Authorised by Union or Member State Law: The decision is authorised by law to which the controller is subject, and which also lays down suitable measures to safeguard the data subject's rights, freedoms, and legitimate interests (e.g., fraud prevention, tax evasion monitoring).

Explicit Consent: The decision is based on the individual's explicit consent. For consent to be valid under GDPR, it must be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous.

Crucially, even when one of these exceptions applies, organisations are still obligated to implement "suitable measures to safeguard the data subject’s rights, freedoms and legitimate interests." These safeguards must, at a minimum, include the data subject's right to obtain human intervention, to express their point of view, and to contest the decision.

How does GDPR address the use of sensitive personal data in ADM and profiling?

The GDPR imposes heightened restrictions on the processing of "special categories of personal data," often referred to as sensitive data (e.g., health data, racial origin, political opinions). Automated processing of these special categories is generally prohibited unless specific conditions from Article 9(2) apply. This typically requires either the data subject's explicit consent for one or more specified purposes, or that the processing is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, based on Union or Member State law that provides suitable and specific safeguards. A complex aspect arises when profiling activities infer sensitive data from seemingly non-sensitive information; if such inferred data falls under special categories, the stricter rules of Article 9(2) apply, along with enhanced safeguards.

What are the key compliance requirements and safeguards for organisations using ADM and profiling?

Organisations must implement robust safeguards and adhere to fundamental data protection principles:

Transparency and Information Obligations: Provide clear, meaningful information about the logic involved in automated decisions, their significance, and envisaged consequences. This includes explaining procedures and principles, not just the data used.

Right to Human Intervention, Express Point of View, and Contest Decision: Individuals must have the right to obtain meaningful human intervention, express their view, and contest automated decisions. Human review must be genuine, with the reviewer having the authority and competence to override the automated outcome.

Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs): Mandatory for ADM and profiling activities likely to result in a high risk to individuals' rights and freedoms, helping to proactively identify and mitigate risks.

Data Minimisation and Purpose Limitation: Collect only the minimum necessary personal data for a specific purpose and do not repurpose data for unrelated ADM without a new legal basis.

Accuracy and Bias Prevention: Ensure the accuracy of data and proactively prevent errors, bias, and discrimination in algorithms and datasets through rigorous review and regular algorithmic audits.

Security Measures: Implement robust technical and organisational security measures commensurate with the risks.

Accountability: Document all compliance efforts, policies, and decisions related to ADM and profiling to demonstrate adherence to GDPR principles.

What are the potential risks and challenges for organisations implementing ADM and profiling?

Organisations face several interconnected challenges and risks:

Algorithmic Opacity (Black Box Problem): Many advanced AI/ML algorithms are complex and opaque, making it difficult to understand how they reach decisions, thus hindering transparency and auditability.

Risk of Hidden Bias and Perpetuating Stereotypes: Algorithms trained on biased data can perpetuate or amplify existing societal biases, leading to discriminatory outcomes. Identifying and mitigating these biases is a significant challenge.

Difficulty in Defining "Meaningful Human Intervention": Translating the requirement for "meaningful human intervention" into practical, scalable mechanisms is complex, especially in high-volume processes.

Invisibility of Profiling to Individuals: Individuals are often unaware that their data is being used for profiling, undermining transparency and individual control.

Ensuring Data Accuracy and Preventing Errors: The effectiveness and fairness of ADM and profiling depend on data accuracy, which is a continuous challenge with large, dynamic datasets.

Balancing Data Minimisation with AI/ML Data Needs: AI models often perform better with vast amounts of data, creating tension with the GDPR's data minimisation principle.

Technological Vulnerabilities: Increased integration of digital tools amplifies the risk of data breaches and cyber threats.

Addressing these challenges requires a holistic approach, combining legal, technical, and organisational measures.

What are the consequences of non-compliance with GDPR regarding ADM and profiling?

Non-compliance with GDPR provisions, particularly concerning ADM and profiling, can lead to severe consequences:

Financial Penalties and Fines: Organisations can face fines up to €20 million or 4% of their total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher. High-profile fines have been levied for transparency infringements, consent issues, and insufficient information about profiling.

Reputational Damage and Loss of Trust: Non-compliance can cause significant negative media coverage, social media backlash, and a profound loss of trust among customers, clients, and employees, which can have long-term adverse effects on customer loyalty and brand image.

Operational Disruptions and Legal Costs: Non-compliance can trigger extensive audits and investigations by Data Protection Authorities (DPAs), leading to operational disruptions, temporary or permanent restrictions on data processing, or orders to erase data. Organisations may also incur substantial legal costs defending against regulatory actions or class-action lawsuits seeking compensation for damages.

These consequences underscore that GDPR compliance is not just a legal obligation but a strategic imperative for maintaining operational resilience, customer relationships, and brand integrity.