GDPR and Facial Recognition Technology

Explore the world of GDPR and how it regulates facial recognition technology. Learn the impact on privacy, security, and rights of data subjects. Stay informed on this evolving landscape!

Staff

This report provides an in-depth analysis of the complex interplay between the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Facial Recognition Technology (FRT). It establishes that FRT unequivocally processes "special category biometric data" under GDPR, subjecting its deployment to the most stringent legal requirements, with explicit consent emerging as the primary, albeit challenging, legal basis. The inherent privacy risks associated with FRT, including pervasive surveillance and algorithmic bias, necessitate robust compliance frameworks such as mandatory Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) and the proactive adoption of Privacy by Design principles.

The analysis highlights critical challenges in FRT deployment, particularly the difficulty of obtaining valid consent in public or imbalanced power dynamics, the risk of "function creep" in data usage, and the irreversible consequences of biometric data breaches. Significant enforcement actions across Europe underscore the increasing regulatory scrutiny and the severe penalties for non-compliance. The evolving regulatory landscape, notably the EU AI Act, signals a more prescriptive future for FRT, introducing outright prohibitions on certain high-risk uses. Organizations deploying FRT must prioritize proactive compliance, ethical considerations, and continuous adaptation to these dynamic legal and ethical demands to mitigate substantial legal and reputational risks.

1. Introduction: Understanding Facial Recognition Technology and GDPR

1.1 What is Facial Recognition Technology (FRT)?

Facial Recognition Technology is a sophisticated form of biometric identification that leverages advanced computational techniques to analyze and measure unique facial features. Its primary function is to verify or ascertain an individual's identity from digital images or video streams. The operational process of FRT typically involves a series of interconnected steps:

Face Detection: The initial step requires the system to accurately locate and isolate human faces within a given image or video frame. This process is frequently enhanced by computer vision and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, which enable faster and more precise detection than human observation alone.

Analysis and Feature Extraction: Once a face is detected, the technology proceeds to digitally map its distinguishing characteristics. This involves measuring specific facial landmarks or "nodal points," such as the precise distance between the eyes, the contours of the cheekbones, the shape of the nose, and the jawline. This geometric data is then transformed into a unique digital representation, commonly referred to as a "faceprint" or "biometric template". Modern FRT systems are capable of assessing over 80 such nodal points to create a highly detailed and distinctive facial signature.

Recognition/Matching: The final stage involves comparing the newly generated faceprint or biometric template against an existing database of known faces. Sophisticated matching algorithms calculate a similarity score between the input template and those stored in the database. If this score surpasses a predefined threshold, the system confirms or identifies the individual's identity.

FRT systems fundamentally rely on a convergence of advanced technologies, including Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, and deep neural networks, which are central to their learning and pattern recognition capabilities. Computer vision techniques are integral for high-level image processing, enabling the systems to interpret visual data effectively. These systems can operate in real-time, known as "live facial recognition," or retrospectively, analyzing pre-recorded footage. Furthermore, their application can be fully automated or serve as a tool to assist human decision-making processes.

The applications of FRT are increasingly diverse and pervasive across various sectors. These include enhancing security protocols at international airports, providing convenient unlocking features for smartphones (such as Apple's Face ID), assisting law enforcement agencies in criminal identification, suspect tracking, and broader public safety initiatives. Beyond these, FRT is utilized for access control in facilities, streamlining banking transactions, and even monitoring student attendance in educational institutions.

The inherent nature of facial recognition technology presents a unique challenge when juxtaposed with data protection principles. FRT's primary function involves identifying individuals based on their physical characteristics, which are frequently captured in public environments. This means that, unlike other forms of identification that require active user input, FRT data collection can occur without an individual's explicit knowledge or active consent. Furthermore, the GDPR's definition of "processing" is expansive, encompassing even "transient processing," where data is briefly created or stored for a fraction of a second. This implies that the mere act of an individual being within the field of view of an FRT system can constitute personal data processing, even if the data is not permanently retained or immediately deleted. This inherent "public" nature of facial features, when converted into the "private" and highly sensitive biometric data under GDPR, creates a fundamental tension. Traditional consent models, which rely on active and informed engagement, become particularly challenging to apply effectively in pervasive public surveillance scenarios. This places a significant burden on organizations to either establish robust alternative legal bases for processing or to implement highly visible and unambiguous transparency measures, acknowledging the inherent difficulty of obtaining true consent in such environments.

1.2 GDPR's Foundational Concepts for FRT

Understanding the General Data Protection Regulation's (GDPR) foundational concepts is crucial for comprehending its application to Facial Recognition Technology.

The GDPR defines 'personal data' broadly as "any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject')". This encompasses a wide array of identifiers, including names, identification numbers, location data, and online identifiers. A natural person is considered identifiable if they can be identified, either directly or indirectly. The explicit inclusion of "indirect identification" in the definition of 'personal data' is critically important for FRT. Even if a "face template"—the mathematical representation of facial features—does not directly contain a person's name, if it can be linked to other unique identifying information available to the data controller or any other party "reasonably likely to use to identify that person," it unequivocally becomes personal data. This means that even seemingly anonymized or pseudonymized facial data, if it retains the potential for re-identification through other available datasets or means, remains firmly within GDPR's scope. This broad interpretation significantly expands the regulatory reach of GDPR beyond just direct identification. It demands a highly cautious approach to any FRT deployment, as organizations must consider not only the immediate data collected but also its potential for re-identification when combined with other information. This places a higher burden on data controllers to ensure true anonymization, or to comply fully with GDPR even for data that might initially appear non-identifiable.

'Biometric data' is a specific and distinct type of personal information, explicitly defined in Article 4(14) of the GDPR. It refers to "personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person, such as facial images or dactyloscopic [fingerprint] data". For information to be classified as biometric data under GDPR, it must satisfy three key criteria: it must relate to the physical, physiological, or behavioral characteristics of a natural person ; it must have been processed using specific technologies, such as an algorithm filtering a human face from an image or software analyzing an audio recording to detect unique vocal qualities ; and crucially, it must enable or confirm the unique identification (recognition) of the person it relates to.

'Special category data' is a designation under Article 9 of the GDPR for certain types of personal information deemed more sensitive, thus requiring an elevated level of protection. Biometric data falls into this category specifically when it is used for the purpose of uniquely identifying someone. This is a crucial distinction, often referred to as "special category biometric data". It is important to note that not all biometric data automatically constitutes special category data; its classification is contingent upon the

purpose of processing. However, even if not used for unique identification, biometric data could still be considered another type of special category information if it can be used to infer other sensitive attributes, such as racial or ethnic origin, or health data.

'Processing' is defined broadly as any operation or set of operations performed on personal data, whether or not by automated means. This encompasses a wide range of activities, including collection, recording, organization, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination, or otherwise making available. Crucially, even transient processing—where information is briefly created, collected, or stored for a fraction of a second—is considered processing and subject to GDPR requirements.

2. Legal Framework: Lawful Processing of FRT Data under GDPR

2.1 The General Prohibition and Article 9 Conditions

Article 9(1) of the GDPR establishes a fundamental general prohibition on the processing of special categories of personal data. This explicitly includes biometric data when it is used for unique identification. This prohibition underscores the high sensitivity and inherent risks associated with such data, reflecting a strong presumption against its widespread use due to its potential for profound impact on individuals' fundamental rights and freedoms.

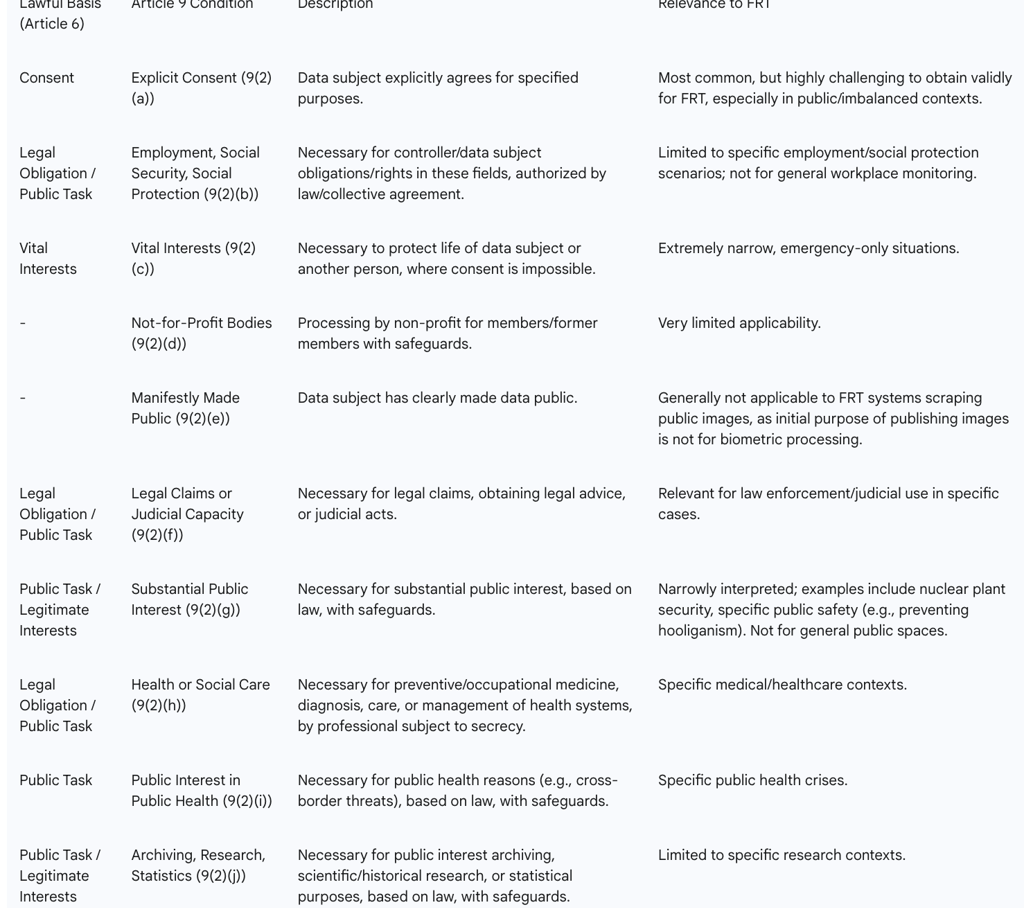

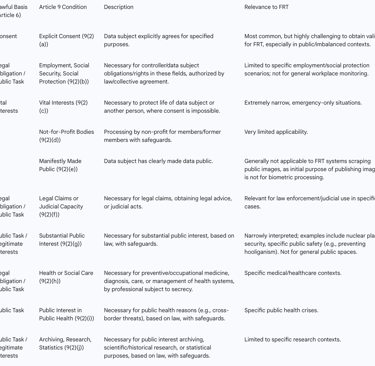

Despite this general prohibition, Article 9(2) outlines a limited set of specific conditions under which processing special category data is permissible. For the lawful processing of biometric data, organizations must identify both a lawful basis under Article 6 of the GDPR and a separate, corresponding condition for processing special category data under Article 9. These two legal bases do not necessarily have to be directly linked, but both must be satisfied simultaneously for processing to be compliant.

2.1.1 The Paramountcy of Explicit Consent: Requirements and Limitations

Explicit consent, as defined in Article 9(2)(a), is frequently cited as the primary and often most appropriate legal basis for processing special category biometric data. For consent to be valid under GDPR, it must meet stringent criteria:

Freely Given: Consent must be provided voluntarily, without any form of coercion, pressure, or undue influence. This requirement is particularly challenging where there is an inherent imbalance of power, such as in employer-employee relationships, interactions between public authorities and citizens, or educational settings. In such contexts, individuals may feel compelled to agree, making it difficult for public authorities and employers to genuinely rely on consent as a freely given basis.

Specific: Consent must be given for one or more clearly defined and specified purposes. This prohibits reliance on broad, generic, or catch-all consent statements.

Informed: The individual must be fully and clearly informed about how their data will be used. This includes understanding the nature of the data being collected, the precise purposes of processing, the identity of the data controller, and any third parties with whom the data might be shared.

Unambiguous: Consent must be signified by a clear affirmative action or statement, leaving no doubt about the data subject's wishes. Silence, pre-ticked boxes, or inactivity are explicitly deemed invalid forms of consent.

Explicit Consent Specifics: Beyond the general requirements for "unambiguous" consent, "explicit" consent implies even stricter conditions. It typically requires a clear statement of agreement, whether oral or written, that specifically identifies the nature of the special category data being processed. Furthermore, it should be distinct and separate from any other consents being sought.

Withdrawal: Data subjects must be explicitly informed of their right to withdraw their consent at any time, and organizations must provide simple and effective mechanisms for such withdrawal.

Despite its paramountcy, relying on explicit consent for FRT deployment faces significant limitations and challenges. The Swedish school case serves as a stark example where consent from students for FRT attendance monitoring was deemed invalid precisely because of the inherent power imbalance between students and the school. This principle has broad implications for employment contexts and public sector deployments, where individuals may not feel they have a genuine choice, making it difficult to establish truly freely given consent. Furthermore, obtaining truly informed and freely given explicit consent for systematic monitoring of individuals in publicly accessible spaces is considered highly unlikely to be appropriate or feasible under GDPR. The mere act of entering a monitored area cannot be assumed to constitute valid consent.

The GDPR sets an exceptionally high standard for consent, particularly the explicit consent required for special categories of data like biometrics. However, FRT, especially when deployed in public or institutional settings, often involves passive data collection or operates within contexts characterized by significant power imbalances. This creates a fundamental conflict: the legal requirement for freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous explicit consent clashes directly with the practical realities of deploying pervasive surveillance technologies where individuals frequently lack real choice, awareness, or the ability to opt-out without detriment. The Swedish school case and the general unsuitability of consent for systematic public monitoring serve as clear illustrations of this dilemma. This means that for many common FRT applications, particularly those in public safety, retail environments, or general access control beyond highly secure, controlled environments, explicit consent is often not a viable or legally sound basis. Consequently, organizations are compelled to seek alternative, much more stringent, Article 9 conditions, or risk significant non-compliance penalties. This legal landscape effectively pushes private FRT use towards niche, high-security applications or those where active user participation and undeniable, genuine consent are integral (e.g., device unlocking, voluntarily consented access control systems). Furthermore, it highlights a broader societal debate about the acceptable limits of surveillance and the erosion of individual autonomy in increasingly monitored environments.

2.1.2 Alternative Conditions for Processing

When explicit consent is not viable or appropriate, organizations must explore alternative conditions under Article 9(2) for processing special category biometric data. For any of these alternative conditions to apply, the processing of biometric data must be demonstrably "necessary" for the stated purpose. "Necessary" implies that the processing is essential and proportionate, meaning it is a targeted and reasonable way to achieve the objective, not merely useful, convenient, or desirable. This often requires a strong justification for why less intrusive or alternative methods are not feasible or would not achieve the same objective.

Key alternative conditions include:

Substantial Public Interest (Article 9(2)(g)): This condition permits processing if it is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, provided it is based on Union or Member State law and includes suitable and specific measures to safeguard data subjects' fundamental rights and interests. Examples where this might apply include the security of a nuclear power plant, where the public interest is of great importance and only a select, vetted group is allowed access. Similarly, ensuring audience security at sports events, as demonstrated by the Brøndby IF football stadium case, has been approved under this basis. However, the concept of "substantial public interest" is interpreted very narrowly by data protection authorities. It must represent a real and substantive public good, not a vague or generic argument. For instance, the Dutch DPA has explicitly stated that the importance of security for recreational areas, repair shops, or supermarkets is generally not significant enough to justify the use of biometric data for access control.

Vital Interests (Article 9(2)(c)): Processing is permissible if it is necessary to protect the vital interests of the data subject or another natural person, particularly when the data subject is physically or legally incapable of giving consent. This condition is intended to cover only interests that are essential for someone's life, such as in medical emergencies where the individual is incapable of giving consent.

Employment, Social Security, and Social Protection Law (Article 9(2)(b)): This condition allows processing necessary for carrying out obligations and exercising specific rights of the controller or data subject in the field of employment and social security and social protection law. This must be authorized by Union or Member State law or a collective agreement, providing appropriate safeguards. It does not, however, cover processing to meet purely contractual employment rights or obligations.

Legal Claims or Judicial Acts (Article 9(2)(f)): Processing is permitted if it is necessary for the establishment, exercise, or defense of legal claims, or whenever courts are acting in their judicial capacity. This is particularly relevant for law enforcement and judicial uses in specific, legally defined contexts.

Public Health (Article 9(2)(i)): This condition allows processing for reasons of public interest in the area of public health, such as protecting against serious cross-border threats to health or ensuring high standards of quality and safety of health care and medicinal products or medical devices. This must be based on Union or Member State law that provides suitable and specific safeguards.

Archiving, Research, or Statistical Purposes (Article 9(2)(j)): Processing is permissible if necessary for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes, or statistical purposes in accordance with Article 89(1). This must be based on Union or Member State law that is proportionate to the aim pursued and includes suitable safeguards.

While Article 9 enumerates several exceptions to the prohibition on processing special category data, a close examination reveals that many of these conditions are heavily qualified by requirements for specific "Union or Member State law" or are inherently tied to specific public sector functions, such as public health, law enforcement, or social security. For private organizations, the "substantial public interest" ground is interpreted very narrowly and is generally difficult to justify outside of highly critical infrastructure. This analysis significantly restricts the practical legal avenues for private companies wishing to deploy FRT. It implies that, outside of very specific, legally mandated, or high-security contexts, explicit consent remains the only broadly applicable and practical Article 9 condition for private sector FRT deployment. This legal landscape effectively forces private companies to either secure genuinely free and informed explicit consent (which, as discussed, is challenging for FRT) or to abandon the use of FRT if no other narrow, specific exception applies to their particular use case. This reinforces the regulatory intent to limit the pervasive use of sensitive biometric data by private actors.

The following table provides a comprehensive summary of the dual legal grounds required for processing biometric data under GDPR:

Table 2: Lawful Bases and Article 9 Conditions for Processing Biometric Data

2.2 Adherence to Core GDPR Principles

Beyond establishing a lawful basis, organizations deploying FRT must rigorously adhere to the core principles of GDPR, which govern all personal data processing.

Data Minimization and Purpose Limitation

The GDPR mandates that personal data, including FRT data, should only be collected for "specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes" – this is the principle of purpose limitation. Complementing this, the principle of data minimization dictates that only the "minimum necessary" data should be collected and processed for that defined purpose. This means organizations must clearly define why they are collecting FRT data before any collection begins. The collected data should not be used for purposes other than those initially stated without a new, legitimate legal basis and explicit consent where required. For example, if FRT is deployed solely for access control, the data should be deleted once access is granted and no longer necessary for that specific purpose. Collecting excessive or irrelevant biometric information is strictly prohibited.

The inherent versatility and technical capabilities of FRT make it particularly susceptible to "function creep," a phenomenon where data initially collected for one specific purpose (e.g., security) is later expanded or repurposed for entirely different uses (e.g., marketing, behavioral analysis, employee monitoring). The GDPR's principles of data minimization and purpose limitation directly counteract this by requiring strict adherence to defined purposes and minimal data retention. However, the technical ease of retaining and re-purposing data often creates a strong temptation for organizations to exploit its potential beyond the initial stated purpose. Organizations must implement robust technical and organizational measures to rigorously enforce purpose limitation and data minimization. This includes establishing automated deletion policies, implementing strict role-based access controls, and regularly auditing data usage to prevent unauthorized repurposing. Failure to do so not only constitutes a clear violation of GDPR but also significantly erodes public trust and increases the risk of data misuse, as re-identification and profiling become easier with larger, more diverse datasets. This also necessitates the establishment of clear and justifiable data retention periods, ensuring that data is not kept for longer than is strictly necessary for the original, specified purpose.

Transparency and Accountability

Organizations must process personal data lawfully, fairly, and in a transparent manner. This fundamental principle requires providing clear, accessible, and easy-to-understand information to data subjects about how their data is collected, the purposes of processing, and with whom their data will be shared. Transparency is particularly challenging for FRT, especially when deployed in public spaces where individuals may be unaware that their data is being collected. Organizations must utilize mechanisms such as comprehensive privacy notices, clear and prominent signage, and other communication methods to inform individuals. Accountability, a related principle, requires organizations to maintain detailed records of processing activities and to be able to demonstrate compliance with all GDPR obligations.

Transparency is a cornerstone of GDPR compliance. However, certain FRT applications, particularly in law enforcement or national security contexts, may operate covertly. The research highlights that covert processing significantly impacts whether the processing is "perceived as fair, transparent and proportionate" by the public. The public's widespread belief, even if legally inaccurate in some specific contexts, that consent is always required for FRT, creates a perception gap that transparency aims to bridge. While overt FRT deployment supports the principles of transparency and fairness, it may, in certain circumstances, reduce the technology's effectiveness for specific objectives (e.g., covert crime detection). Conversely, covert use, even if legally permissible under highly specific law enforcement exceptions, risks severely undermining public trust, increasing public disquiet, and leading to greater legal challenges and complaints. This creates a profound dilemma for policymakers and deployers: prioritizing operational effectiveness might compromise public perception of fairness and fundamental human rights, while prioritizing transparency might limit the technology's utility in sensitive operations. This tension necessitates careful ethical and legal balancing acts.

Data Security and Integrity

Personal data must be processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security, including protection against unauthorized or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction, or damage, using appropriate technical or organizational measures. Given the highly sensitive and unique nature of biometric data, which is intrinsically linked to an individual's identity and cannot be easily changed , robust data security measures are paramount. This includes implementing strong encryption, strict access controls (e.g., role-based access control (RBAC) limiting access to authorized personnel on a need-to-know basis), and pseudonymization techniques. The inherent difficulty in altering or replacing compromised biometric traits makes data security for FRT even more critical, as a breach could lead to irreversible identity theft, fraud, or long-term profiling risks.

Unlike conventional personal data such as passwords or credit card numbers, which can be changed or canceled if compromised, biometric data (like a unique faceprint) cannot be easily altered, revoked, or "reset" if it falls into the wrong hands. A breach of biometric data therefore carries potentially far more severe, permanent, and irreversible consequences for the individual, leading to lifelong risks of identity theft, unauthorized access, or pervasive profiling. This inherent irreversibility of compromised biometric data fundamentally elevates the stakes for data security measures in FRT systems. Organizations must not only implement standard, robust security protocols but also consider advanced, specialized techniques such as homomorphic encryption, secure multi-party computation for biometric templates, or on-device verification where the biometric data never leaves the user's control. Furthermore, comprehensive and tailored incident response plans are crucial, acknowledging the unique challenges of mitigating harm from biometric data breaches. The potential for severe, long-term harm to data subjects means that regulatory bodies will likely impose and enforce exceptionally high expectations for security in this domain.

3. Compliance Obligations and Best Practices for Organizations

3.1 Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs): Mandatory for High-Risk Processing

Organizations are unequivocally mandated to conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) before implementing Facial Recognition Technology. This requirement stems from the inherent nature of processing biometric data, particularly for unique identification, which is considered "likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons".

The DPIA serves as a crucial proactive measure designed to achieve several objectives:

It evaluates the potential impact of the technology on individuals' privacy and other fundamental rights.

It determines whether the proposed use of FRT is both "necessary and proportionate" to the intended purpose, ensuring that the benefits genuinely outweigh the risks.

It systematically identifies and mitigates privacy and security risks associated with processing biometric data.

For public deployments, it assesses risks to broader fundamental rights beyond privacy, such as freedom of movement, free speech, and the right to non-discrimination.

It defines and necessitates the implementation of "safeguards, security measures and mechanisms" to effectively mitigate the identified risks.

The DPIA, particularly for technologies as impactful as FRT, is not merely a one-time compliance checkbox or a bureaucratic formality. Instead, it serves as a dynamic and continuous tool for ongoing risk management, ethical consideration, and accountability throughout the technology's lifecycle. Its explicit requirement to assess "necessity and proportionality" compels organizations to critically examine whether FRT is genuinely the least intrusive and most effective means to achieve their objective, and whether the societal benefits truly outweigh the inherent risks and potential intrusion into individual rights. This implies a continuous ethical reflection that extends beyond mere legal adherence. Organizations should therefore view DPIAs as "living documents" that are regularly reviewed, updated, and re-evaluated, especially as FRT capabilities evolve, new use cases emerge, or the context of deployment changes. This iterative process fosters a robust culture of privacy by design and ensures that complex ethical considerations, such as potential algorithmic biases and unforeseen consequences , are addressed proactively and systematically throughout the technology's development, deployment, and operational phases.

3.2 Upholding Data Subject Rights: Access, Rectification, Erasure, and Objection

The GDPR grants data subjects several fundamental rights regarding their personal data. For FRT, these rights are particularly salient given the sensitive nature of the data and the potential for significant impact on individuals:

Right of Access (Article 15): Individuals have the right to obtain confirmation as to whether or not personal data concerning them is being processed. Where processing occurs, they have the right to access that personal data and supplementary information, often through a Subject Access Request (SAR).

Right to Rectification (Article 16): Individuals have the right to obtain the rectification of inaccurate personal data concerning them without undue delay. This right is critically important for FRT due to the documented risks of algorithmic biases and potential misidentifications, which can lead to severe real-world consequences.

Right to Erasure ('Right to be Forgotten') (Article 17): Data subjects have the right to obtain the erasure of personal data concerning them without undue delay under specific circumstances.

Right to Restriction of Processing (Article 18): Individuals have the right to obtain restriction of processing in certain situations, for example, if the accuracy of the data is contested.

Right to Object (Article 21): Data subjects have the right to object to the processing of their personal data, especially when the processing is based on legitimate interests or public interest.

Upholding these rights in the context of FRT presents technical challenges. For example, removing an individual's data from a trained AI model, particularly deep neural networks, may require costly and complex retraining of the entire system. Organizations need to design systems that can effectively respond to these requests, thereby respecting privacy by design.

The "Right to be Forgotten" (Article 17) faces a unique challenge when applied to biometric data due to its immutable nature. Unlike conventional personal data that can be easily deleted or altered, biometric data, such as a unique faceprint, is derived from inherent physical characteristics that cannot be changed or "reset" if compromised. This creates a fundamental conflict between the data subject's right to erasure and the technical and practical difficulties of effectively deleting or anonymizing biometric templates from large, distributed databases, especially those used for AI training. The challenge is compounded when biometric data is integrated into complex AI models, where removing specific data points may necessitate extensive and costly retraining, potentially impacting the model's overall integrity and performance. This places a heightened responsibility on data controllers to implement robust mechanisms that genuinely facilitate the right to erasure, even if it means exploring advanced techniques like differential privacy or secure multi-party computation to minimize the retention of identifiable biometric information. The practical limitations in fully achieving the "right to be forgotten" for biometric data underscore the critical importance of preventing its unauthorized collection and ensuring its utmost security from the outset.

3.3 Privacy by Design and Default

The principle of Privacy by Design and Default (PbD) under GDPR (Article 25) requires organizations to proactively integrate data protection safeguards into the design of their processing systems and to ensure that, by default, only necessary personal data is processed. For FRT, this means embedding privacy measures from the earliest stages of system conception and development, rather than as an afterthought. This includes implementing data minimization techniques, ensuring pseudonymization or anonymization where possible, employing robust encryption, and establishing strict access controls.

The proactive integration of privacy measures from the outset, as mandated by Privacy by Design, is crucial for technologies as intrusive as FRT. It moves beyond reactive compliance to foster a culture of ethical and responsible innovation. By designing systems with privacy as a core requirement, organizations can build greater trust with data subjects and mitigate potential risks before they materialize. This approach ensures that data protection is not merely an add-on but an intrinsic component of the FRT system's architecture and operational processes. It compels organizations to consider the privacy implications at every stage, from data collection methods to storage, processing, and eventual deletion, thereby reducing the likelihood of non-compliance and enhancing the overall security and ethical standing of the technology.

3.4 Ethical Considerations and Algorithmic Bias

Beyond legal compliance, the deployment of FRT raises significant ethical considerations, touching upon fundamental human rights and societal values. Primary concerns include the potential for pervasive surveillance, which can infringe upon individual privacy and autonomy, and the broader implications for human dignity. The ability of FRT to track individuals in public spaces without their awareness or consent transforms these areas into zones of potential constant monitoring, raising profound questions about freedom of movement and expression.

A critical ethical issue is the documented problem of algorithmic bias within FRT systems. Research has consistently shown that many current systems exhibit lower accuracy rates for certain demographic groups, particularly women and people of color, as well as older individuals and children. This bias can lead to misidentifications, false positives, or false negatives, resulting in potential discrimination, unfair treatment, or even severe real-world harm for those wrongly singled out or overlooked. For instance, misidentification by law enforcement could lead to wrongful arrests or disproportionate scrutiny of certain communities.

Mitigation strategies for algorithmic bias are essential. These include ensuring that training data sets are diverse and representative of the populations on whom the technology will be used. Regular external auditing of algorithms can help identify and address hidden biases. Furthermore, employing de-biasing techniques during algorithm development and ensuring human oversight in decision-making processes where FRT is used are crucial steps to prevent discriminatory outcomes.

The imperative of ethical AI and human oversight extends beyond mere legal compliance. It embodies a commitment to developing and deploying FRT responsibly, ensuring that its benefits do not come at the cost of fundamental rights. This requires organizations to establish robust ethical frameworks that guide the entire lifecycle of FRT systems, from conception to deployment and ongoing operation. Human intervention in automated decisions, particularly those with legal or similarly significant effects on individuals (Article 22 GDPR), is vital to prevent errors and mitigate the impact of algorithmic biases. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of FRT systems are necessary to detect and rectify any unintended consequences or discriminatory impacts, ensuring fairness and upholding human rights in practice. This proactive ethical stance builds trust and ensures that the technology serves society equitably.

4. Enforcement Actions and Regulatory Landscape

4.1 Key Enforcement Cases

The application of GDPR to Facial Recognition Technology has led to several significant enforcement actions across Europe, highlighting key compliance challenges and regulatory interpretations.

Swedish School Case

In 2019, a Swedish school faced a penalty under GDPR for utilizing facial recognition technology to monitor student attendance. The school argued that the technology was efficient and that students had provided their consent. However, the Swedish Data Protection Authority (DPA) determined that the consent was not legally valid. This was primarily due to the inherent dependent relationship between the students and the school, which meant the consent could not be considered "freely given". Additionally, the DPA found that less intrusive methods for tracking attendance were available, rendering the use of FRT disproportionate to the stated purpose. The school was consequently fined for non-compliance with GDPR.

Clearview AI Cases

The cases involving Clearview AI represent some of the most high-profile and impactful enforcement actions concerning FRT under GDPR.

Clearview AI's business model involves building a massive database of facial images by scraping billions of photos from publicly available sources on the internet, including social media and news sites. The company then processes these images to create unique biometric codes (faceprints) and offers access to this database as a search engine service primarily to law enforcement, military, and intelligence organizations.

This business model has led to significant multi-jurisdictional fines across Europe:

Dutch Data Protection Authority (DPA): Fined Clearview AI €30.5 million (approximately $34 million) for violating GDPR, specifically for building an "illegal database with billions of photos of faces" without consent or knowledge of the individuals.

Italian Data Protection Authority (Garante): Fined Clearview AI €20 million in 2022, ruling that the company had violated GDPR rules around transparency, purpose limitation, and storage limitation. The company was also ordered to delete Italians' personal data from its database.

French Data Protection Authority (CNIL): Imposed a €20 million fine in October 2022, ordering Clearview AI not to collect and process data on individuals located in France without a legal basis and to delete existing data. Due to non-compliance, the CNIL imposed an additional overdue penalty payment of €5.2 million in April 2023.

Other European Regulators: Regulators in Greece and Austria have also ordered Clearview AI to delete European citizens' data and imposed penalties.

These enforcement actions consistently cited Clearview AI's failure to obtain explicit consent, its lack of transparency regarding data collection, the absence of a valid legal basis for processing biometric data on such a mass scale, and breaches of data minimization and storage limitation principles.

Despite these significant fines, Clearview AI has largely resisted compliance, claiming it is not subject to GDPR regulations because it does not have a place of business in the EU. This stance has created significant jurisdictional challenges for EU DPAs, who lack direct jurisdiction to seize assets or compel payment in the US, often relying on international cooperation.

The UK Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) also issued an enforcement notice and a £7.5 million fine against Clearview AI in May 2022, ordering the deletion of UK individuals' data. However, in October 2023, a UK First-tier Tribunal overturned this action. The tribunal accepted Clearview's argument that its services were provided exclusively to non-UK/EU law enforcement agencies, and therefore its processing fell outside the scope of the UK GDPR due to the "foreign law enforcement" exception. The ICO subsequently announced its intention to appeal this judgment, seeking clarification on whether commercial enterprises profiting from processing digital images of UK individuals can claim to be engaged in "law enforcement" activities that exempt them from GDPR.

Finnish Police Reprimand

In October 2021, the Finnish Data Protection Ombudsman issued a statutory reprimand to the National Police Board for illegal processing of special categories of personal data during a facial recognition technology trial. A unit of the National Bureau of Investigation had experimented with FRT to identify potential victims of child sexual abuse. The key findings indicated a failure in the controller's responsibility, as the processing of personal data was performed without the approval of the National Police Board. Furthermore, the police had not considered the stringent requirements for processing special categories of personal data and had not determined in advance how long the data would be stored or whether it could be disclosed to third parties. The Police Board was ordered to notify data subjects of the breach and request Clearview AI to erase the data transmitted by the police.

The Clearview AI cases underscore GDPR's extraterritorial reach (Article 3), which aims to protect EU residents' data regardless of where the processing organization is based. However, these cases also highlight significant practical challenges in enforcing penalties against non-EU entities without physical presence or assets within the EU. The differing outcomes, particularly the UK tribunal's decision regarding the "foreign law enforcement" exception, illustrate the complexities of jurisdictional interpretations and the limitations of enforcement without robust international cooperation mechanisms. This means that while GDPR aims for global protection of EU citizens' data, effective enforcement against entities operating solely outside the EU remains a complex and evolving area, often requiring international cooperation or novel legal strategies. For organizations, it reinforces the critical importance of understanding not only GDPR's principles but also the nuances of its territorial scope and the specific interpretations by national supervisory authorities. The ongoing legal battles also signal that the regulatory framework is still adapting to the global nature of data processing by advanced AI systems.

4.2 Evolving Regulatory Landscape: The EU AI Act and Beyond

The regulatory landscape governing Facial Recognition Technology is rapidly evolving, with the European Union taking a leading role in shaping future legal frameworks through the EU AI Act.

EU AI Act's Impact on FRT

The EU AI Act represents a significant legislative development that directly impacts FRT, moving beyond the general principles of GDPR to introduce technology-specific regulations:

High-Risk Classification: The Act classifies remote biometric identification systems as "high-risk" AI systems. This designation triggers stringent compliance obligations for deployers, including requirements for robust risk management systems, strong data governance practices, human oversight mechanisms, and registration in the EU's public database for high-risk AI systems.

Prohibitions: The Act introduces outright prohibitions on certain FRT uses, reflecting a strong stance against mass surveillance and discriminatory practices:

It absolutely prohibits the development or expansion of facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage. This ban is absolute, with no exceptions.

The use of "real-time" remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement purposes is generally banned, except in narrowly defined and strictly necessary circumstances, subject to judicial authorization and proportionality requirements.

Biometric categorization systems that categorize individuals according to certain prohibited characteristics, such as race, political opinions, trade union membership, religion, and sexual orientation, are banned, with only limited exceptions for specific purposes like labeling or filtering biometric datasets.

Distinction: The Act carefully distinguishes between remote biometric identification (systems that identify individuals without their active involvement, typically at a distance) and biometric verification or authentication tools (where the user actively participates, such as fingerprint scanning for unlocking a smartphone or building access control). The latter are generally subject to less stringent regulations.

UK Regulatory Stance

While the UK GDPR (implemented through the Data Protection Act 2018) continues to regulate FRT, the UK's approach to AI regulation is diverging from the EU's. The Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) has published guidance on biometric recognition systems, but this guidance largely relies on existing GDPR principles and does not introduce new specific legislation for FRT use by law enforcement or private companies beyond the established GDPR framework. Critics argue that the UK's current governance framework for FRT is inadequate, creating legal uncertainty and undermining public trust, leading to calls for new, risk-based legislation to provide clearer rules and independent oversight.

Global Trends and Calls for Regulation

The increasing pervasiveness of FRT across various applications has sparked global concerns over surveillance, privacy, and algorithmic bias. This has led to widespread calls for stricter regulation from civil society groups, privacy advocates, and even technology leaders. Some jurisdictions have already considered or implemented outright bans on certain uses of FRT by law enforcement agencies or in public spaces. This global trend indicates a growing recognition of the need to balance technological innovation with fundamental human rights.

The EU AI Act represents a significant step beyond GDPR, introducing specific, technology-centric regulations for FRT, including outright bans on certain uses. This contrasts with the UK's current approach, which largely relies on existing GDPR principles, leading to a "legal grey area" and calls for new legislation. This divergence means that organizations operating internationally must navigate increasingly complex and potentially conflicting regulatory frameworks. This regulatory fragmentation creates compliance complexities for global businesses and developers of FRT. A system designed to be compliant in one jurisdiction might fall foul of rules in another, necessitating a highly adaptable and jurisdiction-specific compliance strategy. The EU's proactive, restrictive stance on certain FRT uses (e.g., untargeted scraping, real-time public identification) could set a global precedent, influencing future regulatory developments elsewhere. Conversely, a less prescriptive approach in other regions might foster innovation but potentially at the cost of privacy and fundamental rights. This dynamic landscape demands continuous monitoring and legal counsel to ensure adherence across diverse operational territories.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1 Synthesized Conclusions

The analysis unequivocally establishes that Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) processes "special category biometric data" under the GDPR, thereby triggering the most stringent data protection requirements. Lawful processing necessitates satisfying both a general lawful basis under Article 6 and a specific condition under Article 9. For private entities, explicit consent emerges as the primary, yet profoundly challenging, legal ground, often proving unviable in contexts marked by power imbalances or pervasive public surveillance.

The mandatory Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) is not merely a compliance formality but a critical, continuous ethical and legal compass. It compels organizations to rigorously assess the necessity and proportionality of FRT deployments, ensuring that the technology's benefits genuinely outweigh the inherent risks to fundamental rights. The irreversible nature of biometric data compromise, unlike other forms of personal data, elevates security imperatives to an unprecedented level, demanding state-of-the-art protection measures and meticulous incident response planning.

Furthermore, the pervasive issue of algorithmic bias within FRT systems necessitates a proactive ethical stance, extending beyond legal adherence to ensure fairness and prevent discrimination. Finally, recent enforcement actions across Europe, particularly the multi-jurisdictional fines against Clearview AI and the Swedish school case, underscore the robust regulatory scrutiny and the significant penalties for non-compliance. The advent of the EU AI Act signifies a pivotal shift towards more prescriptive, technology-specific regulation, including outright prohibitions on certain high-risk FRT uses, creating a diverging and increasingly complex global regulatory landscape for organizations to navigate.

5.2 Strategic Recommendations for Organizations Deploying FRT

Given the complex legal and ethical landscape surrounding Facial Recognition Technology, organizations considering or currently deploying FRT should adopt a multi-faceted strategic approach to ensure compliance and mitigate risks:

Prioritize Privacy by Design and Default: Integrate data protection principles from the earliest stages of FRT system development and deployment. This means building in data minimization, purpose limitation, robust encryption, and strict access controls as foundational elements, rather than as afterthoughts.

Conduct Rigorous and Ongoing DPIAs: Treat Data Protection Impact Assessments as dynamic, living documents. Regularly review and update DPIAs throughout the FRT system's lifecycle to continuously assess necessity, proportionality, and to identify and mitigate evolving risks. This process should proactively address ethical considerations, including potential algorithmic biases and unforeseen consequences.

Re-evaluate Lawful Basis with Caution: For private entities, assume explicit consent is the default and most challenging legal basis for processing biometric data. Explore other Article 9 conditions only if demonstrably necessary and proportionate, and if a clear legal basis exists in Union or Member State law, acknowledging the narrow and specific scope of these exceptions.

Enhance Transparency and Communication: Provide clear, prominent, and easily understandable information to data subjects about the use of FRT, the specific data collected, the precise purposes of processing, and data retention periods. This is particularly critical in public settings where individuals may not actively engage with privacy notices.

Implement Advanced Security Measures: Given the irreversible nature of biometric data compromise, invest in state-of-the-art security protocols. This includes robust encryption, strict role-based access controls, and consideration of privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) like on-device processing where biometric data never leaves the user's control.

Address Algorithmic Bias Proactively: Implement comprehensive strategies to detect and mitigate bias in FRT algorithms. This involves utilizing diverse and representative training data, conducting regular independent audits of algorithmic fairness, and incorporating human oversight in any automated decision-making processes to prevent discrimination and ensure equitable outcomes.

Establish Robust Data Subject Rights Mechanisms: Develop clear, efficient, and accessible processes for handling data subject requests, including the right to access, rectification, erasure, and objection. Recognize the technical complexities associated with fulfilling these rights for biometric data and invest in solutions that enable genuine compliance.

Monitor Regulatory Developments Continuously: Stay abreast of evolving national and EU-level regulations, particularly the comprehensive provisions of the EU AI Act and any new guidance issued by supervisory authorities. Adapt compliance strategies dynamically to adhere to these changing legal requirements across all operational territories.

Seek Expert Legal Counsel: Given the inherent complexity, high-risk classification, and evolving nature of FRT under GDPR and emerging AI regulations, engaging with specialized legal and privacy experts is crucial for navigating compliance challenges, interpreting nuanced legal requirements, and ensuring responsible and lawful deployment.

FAQ

1. What exactly is Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) and how does the GDPR classify the data it processes?

Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) is an advanced biometric identification system that analyses and measures unique facial features from digital images or video streams to verify or ascertain an individual's identity. It operates in several steps: initially detecting a face, then extracting distinguishing characteristics (like the distance between eyes or the shape of the jawline) to create a unique digital representation called a "faceprint" or "biometric template," and finally comparing this faceprint against a database for recognition. FRT systems leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, and computer vision and can operate in real-time or retrospectively.

Under the GDPR, data processed by FRT is classified as "special category biometric data" when used for unique identification. This classification is crucial because it triggers the most stringent data protection requirements. The GDPR broadly defines "personal data" as any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. "Biometric data" specifically refers to personal data resulting from technical processing relating to physical, physiological, or behavioural characteristics that allow unique identification. When biometric data is used for this purpose of unique identification, it becomes "special category data," requiring elevated protection due to its sensitive nature and the inherent risks associated with its processing. Even transient processing of facial images, or if a face template can be linked to other identifying information, constitutes personal data processing under GDPR.

2. Why is obtaining explicit consent for FRT deployment often so challenging under GDPR, especially in public spaces?

Obtaining explicit consent for FRT deployment is often profoundly challenging under GDPR, particularly in public spaces or contexts with imbalanced power dynamics, due to the stringent criteria consent must meet:

Freely Given: Consent must be voluntary, without coercion or undue influence. In scenarios like employer-employee relationships, public authorities and citizens, or educational settings, individuals may feel compelled to agree, undermining the "freely given" requirement. The Swedish school case, where student consent for FRT attendance monitoring was deemed invalid due to the power imbalance, exemplifies this.

Specific and Informed: Consent must be for clearly defined purposes, and the individual must be fully informed about how their data will be used, including who the data controller is and who data might be shared with. This is difficult to achieve when individuals are passively monitored in public.

Unambiguous and Explicit: Consent requires a clear affirmative action, not silence or pre-ticked boxes. For "explicit" consent, a clear statement specifically identifying the sensitive biometric data being processed is needed. It's considered highly unlikely that entering a publicly accessible space can constitute valid, explicit consent for systematic FRT monitoring.

Withdrawal: Individuals must be informed of their right to withdraw consent easily, which is practically complex in pervasive surveillance systems.

The inherent conflict arises because FRT often involves passive data collection in environments where individuals lack real choice or awareness, directly clashing with GDPR's high standards for genuine, active, and informed consent. Consequently, for many common FRT applications, explicit consent is often not a legally sound basis, forcing organisations to seek alternative, much narrower, and more stringent Article 9 conditions.

3. What are the main alternatives to explicit consent for processing biometric data under GDPR, and why are they generally limited for private organisations?

When explicit consent for processing special category biometric data is not viable, organisations must explore alternative conditions under Article 9(2) of GDPR. However, these alternatives are generally very limited for private organisations:

Substantial Public Interest (Article 9(2)(g)): This condition permits processing necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, provided it is based on Union or Member State law and includes suitable safeguards. This is interpreted very narrowly by data protection authorities and typically applies to highly critical infrastructure (e.g., nuclear power plants) or specific public safety objectives (e.g., preventing hooliganism at sports events, as seen in the Brøndby IF stadium case). It's rarely applicable for general private sector uses like retail security.

Vital Interests (Article 9(2)(c)): This applies only in emergencies, where processing is essential to protect someone's life and the data subject is physically or legally incapable of giving consent. It's an extremely narrow, emergency-only basis.

Employment, Social Security, and Social Protection Law (Article 9(2)(b)): This allows processing necessary for specific obligations or rights in these fields, authorised by law or collective agreement. It does not cover general workplace monitoring.

Legal Claims or Judicial Acts (Article 9(2)(f)): This is primarily relevant for law enforcement and judicial uses in specific, legally defined contexts.

Public Health (Article 9(2)(i)) and Archiving, Research, or Statistical Purposes (Article 9(2)(j)): These conditions are tied to specific public health, research, or statistical objectives, requiring a basis in Union or Member State law and suitable safeguards, making them generally inapplicable for commercial FRT.

Many of these alternative conditions are heavily qualified by requirements for specific "Union or Member State law" or are inherently tied to specific public sector functions. For private companies, justifying the "substantial public interest" ground is very difficult outside of highly critical infrastructure. This significantly restricts the practical legal avenues for private companies, effectively pushing them to either secure genuinely free and informed explicit consent or to abandon the use of FRT if no other narrow, specific exception applies to their particular use case.

4. What are the key GDPR principles organisations must adhere to when deploying FRT, beyond establishing a lawful basis?

Beyond establishing a lawful basis, organisations deploying FRT must rigorously adhere to core GDPR principles:

Data Minimisation and Purpose Limitation: FRT data must only be collected for "specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes" (purpose limitation), and only the "minimum necessary" data should be collected and processed for that defined purpose (data minimisation). This prevents "function creep," where data collected for one purpose is later expanded for different uses (e.g., security data used for marketing). Data must not be kept longer than strictly necessary.

Transparency and Accountability: Organisations must process data lawfully, fairly, and transparently, providing clear and accessible information to data subjects about data collection, purposes, and sharing. For FRT, this means prominent signage and comprehensive privacy notices, especially in public spaces where individuals might be unaware of collection. Accountability requires maintaining detailed records and demonstrating compliance.

Data Security and Integrity: Personal data must be processed securely, protected against unauthorised or unlawful processing, and accidental loss or damage. Given the sensitive and immutable nature of biometric data (which cannot be easily changed if compromised), robust security measures like strong encryption, strict access controls, and pseudonymisation are paramount. A breach of biometric data carries severe, irreversible consequences, elevating the stakes for security measures.

Adherence to these principles is crucial for building trust, mitigating risks, and preventing misuse of sensitive biometric information.

5. Why are Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) mandatory for FRT, and what ethical considerations must they address?

Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) are unequivocally mandated before implementing Facial Recognition Technology because processing biometric data for unique identification is considered "likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons."

DPIAs serve as crucial proactive measures to:

Evaluate Impact: Assess the potential impact on individuals' privacy and other fundamental rights.

Determine Necessity and Proportionality: Ensure the proposed use of FRT is genuinely "necessary and proportionate" to the intended purpose, meaning benefits truly outweigh risks. This compels critical examination of whether FRT is the least intrusive and most effective method.

Identify and Mitigate Risks: Systematically pinpoint and reduce privacy and security risks associated with biometric data processing.

Define Safeguards: Specify and necessitate the implementation of technical and organisational safeguards.

Assess Broader Rights: For public deployments, evaluate risks to fundamental rights beyond privacy, such as freedom of movement, free speech, and non-discrimination.

Beyond mere legal compliance, DPIAs for FRT compel continuous ethical reflection. They must proactively address significant ethical considerations, particularly algorithmic bias. Many FRT systems show lower accuracy for certain demographic groups (e.g., women, people of colour, older individuals, children), leading to potential misidentifications, false positives, or false negatives, and consequently, discrimination or unfair treatment. DPIAs should ensure that algorithms are fair, training data is diverse, and human oversight is integrated to prevent discriminatory outcomes. The DPIA should be a dynamic, "living document," regularly reviewed to address evolving capabilities, new use cases, and unforeseen ethical implications throughout the technology's lifecycle.

6. What unique challenges does the "Right to be Forgotten" (Right to Erasure) present for biometric data processed by FRT systems?

The "Right to be Forgotten" (Article 17 GDPR), or the Right to Erasure, presents unique and significant challenges when applied to biometric data processed by FRT systems due to its immutable nature.

Unlike conventional personal data (like passwords or credit card numbers) that can be easily deleted or altered if compromised, biometric data, such as a unique faceprint, is derived from inherent physical characteristics of an individual. These characteristics cannot be changed or "reset" if the data is compromised or if an individual requests its erasure.

This creates a fundamental conflict:

Immutability: A unique faceprint is intrinsically linked to an individual's identity and cannot be easily changed or revoked.

Technical Difficulty: Effectively deleting or anonymising biometric templates from large, distributed databases, especially those used for AI training, can be technically complex and costly. Removing specific data points from intricate AI models (like deep neural networks) may necessitate extensive and costly retraining of the entire system, potentially impacting its overall integrity and performance.

Irreversible Consequences of Breach: If biometric data falls into the wrong hands, the consequences for the individual can be far more severe, permanent, and irreversible than with other data types, leading to lifelong risks of identity theft, fraud, or pervasive profiling, precisely because the compromised biometric trait cannot be easily altered or replaced.

This heightened difficulty in fulfilling the Right to Erasure underscores the critical importance of preventing unauthorised collection of biometric data and ensuring its utmost security from the outset. Organisations must invest in robust mechanisms and potentially advanced techniques (like differential privacy or secure multi-party computation) to genuinely facilitate this right, despite the inherent technical and practical limitations.

7. How have key enforcement actions shaped the interpretation and enforcement of GDPR for FRT?

Key enforcement actions across Europe have significantly shaped the interpretation and enforcement of GDPR for FRT, highlighting critical compliance challenges and regulatory scrutiny:

Swedish School Case (2019): This case established that consent for FRT is invalid when there's an inherent power imbalance (e.g., students and school). It demonstrated that even with purported consent, a DPA can deem it not "freely given" and find the use of FRT disproportionate if less intrusive methods exist, leading to a fine for non-compliance.

Clearview AI Cases (Dutch, Italian, French, UK DPAs): These multi-jurisdictional cases against Clearview AI, which scraped billions of facial images from the internet to build a database for law enforcement, underscore several key points:

Strict interpretation of consent and legal basis: Clearview AI was consistently fined for failing to obtain explicit consent and lacking a valid legal basis for processing biometric data on a mass scale.

Extraterritorial reach of GDPR (Article 3): These cases demonstrated GDPR's aim to protect EU residents' data regardless of where the processing organisation is based, even if it has no physical EU presence.

Challenges of enforcement: Clearview AI's resistance to compliance and claims of not being subject to GDPR highlight practical difficulties in enforcing penalties against non-EU entities without physical assets within the EU, often requiring international cooperation.

Jurisdictional complexities: The UK tribunal's decision to overturn the ICO's fine, accepting Clearview's argument of a "foreign law enforcement" exception, illustrates the complexities of legal interpretations and ongoing debates about GDPR's scope.

Finnish Police Reprimand (2021): This reprimand to the National Police Board for illegal processing during an FRT trial for identifying child sexual abuse victims highlighted failures in controller responsibility, lack of prior approval, and not considering stringent special category data requirements (e.g., data storage periods, disclosure to third parties).

These cases collectively demonstrate robust regulatory scrutiny, severe penalties for non-compliance, and the ongoing challenges of enforcing GDPR in a globally interconnected digital landscape where sophisticated AI systems operate across borders. They reinforce the paramount importance of explicit consent (where feasible), strict adherence to core GDPR principles, and the requirement for a clear legal basis for FRT deployment.

8. How is the EU AI Act set to further impact the regulation of FRT beyond GDPR?

The EU AI Act represents a significant legislative development that will profoundly impact FRT, moving beyond GDPR's general principles to introduce more prescriptive, technology-specific regulations:

High-Risk Classification: The Act unequivocally classifies remote biometric identification systems as "high-risk" AI systems. This designation triggers stringent compliance obligations, including robust risk management systems, strong data governance, human oversight mechanisms, and registration in the EU's public database for high-risk AI.

Outright Prohibitions: The Act introduces absolute bans on certain FRT uses, reflecting a strong stance against mass surveillance and discriminatory practices:

Untargeted Scraping: Prohibits the development or expansion of facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage, with no exceptions. This directly targets business models like Clearview AI's.

Real-time Public Use by Law Enforcement: Generally bans the use of "real-time" remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement, with only very narrowly defined and strictly necessary exceptions requiring judicial authorisation and proportionality.

Biometric Categorisation based on sensitive characteristics: Bans systems that categorise individuals by prohibited characteristics like race, political opinions, or sexual orientation, with only limited exceptions.

Distinction between Identification and Verification: The Act differentiates between "remote biometric identification" (identifying individuals without their active involvement) and "biometric verification/authentication" (where users actively participate, like unlocking a smartphone). The latter is generally subject to less stringent regulation.

While the UK's approach to AI regulation is diverging, largely relying on existing GDPR principles, the EU AI Act's proactive and restrictive stance on certain FRT uses could set a global precedent. This regulatory fragmentation means organisations operating internationally must navigate increasingly complex and potentially conflicting legal frameworks, necessitating a highly adaptable and jurisdiction-specific compliance strategy. The Act signifies a pivotal shift towards a future where FRT is not just broadly regulated by data protection laws, but also specifically constrained by AI-centric legislation that aims to mitigate its inherent risks to fundamental rights.