Right to Be Forgotten Implementation

Explore the intricacies of the Right to Be Forgotten, its practical implementation across industries, key challenges, and strategic approaches for effective compliance in the digital age.

The "Right to be Forgotten" (RTBF) represents a pivotal legal concept in the digital age, granting individuals the ability to request the removal of their personal data from online platforms and search engine results when such information is deemed outdated, irrelevant, or potentially harmful to their reputation. This right is frequently invoked interchangeably with the "right to erasure," a term specifically codified under Article 17 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union and its counterpart, the UK GDPR, in the United Kingdom.

While these terms are often used synonymously, a critical distinction exists that carries significant implications for practical application and legal interpretation. The RTBF primarily pertains to the delisting of links to personal data from search engine results, aiming to reduce the discoverability of information online. This means the original content may remain on the internet, but it becomes significantly harder to find through common search queries. Conversely, the broader Right to Erasure, as outlined in Article 17, mandates the actual deletion of personal data held by an organization across all its systems and contexts. This encompasses internal databases, customer relationship management (CRM) systems, marketing lists, and even backup archives.

This difference in focus means that comprehensive compliance demands a multi-faceted approach from organizations. Successfully delisting content from search engines addresses the RTBF aspect, mitigating reputational harm by making information less accessible. However, this does not absolve the organization of its separate and equally stringent obligations to erase the underlying data from its own systems, which falls under the Right to Erasure. This requires distinct compliance strategies, tailored technical capabilities, and robust internal policies for each type of request. The right generally applies to data held at the time a request is received and does not extend to data that may be created in the future.

1.2 Historical Origins: The Google Spain Case and its Legacy

The conceptual genesis of the Right to be Forgotten can be traced to Europe, gaining widespread international recognition following the landmark 2014 ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the case of Google Spain SL, Google Inc v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos, Mario Costeja González. This pivotal decision arose from a Spanish citizen's request to Google to remove links to an old newspaper article concerning a forced property auction due to debt, arguing the information was no longer relevant.

In its judgment, the ECJ ruled that individuals possess the right to request search engines, such as Google, to remove links to information about them that is "inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant or excessive" in light of the time elapsed. The Court determined that the fundamental right to privacy could, under specific circumstances, supersede the economic interests of commercial search firms and, at times, the public interest in accessing information. Crucially, the ruling did not compel original publishers, such as newspapers, to remove their articles, but rather required search engines to de-index them from search results.

This ruling marked a significant paradigm shift, establishing a legal precedent that classified search engine operators as "data controllers" responsible for the processing of personal information that appears on third-party web pages. This designation effectively shifted a substantial portion of the "information control" and "censorship" burden from governmental bodies or original content publishers directly onto private technology companies. Search engines, now acting as de facto arbiters, are compelled to balance often competing fundamental rights: an individual's right to privacy versus the right to freedom of expression and the public's right to know, on a case-by-case basis. This is a role for which private entities are not inherently designed or legally equipped, leading to inherent complexities in its application.

The "outsourcing" of such nuanced legal and societal judgments to private companies can result in inconsistencies in application, potential for algorithmic bias, and ongoing criticisms regarding the effectiveness and fairness of RTBF implementation. This situation highlights a fundamental tension in governing information in the digital age, where the technical architecture of the internet, particularly search engines, becomes a central point for human rights enforcement. The

Google Spain judgment subsequently influenced the explicit codification of the Right to Erasure in Article 17 of the GDPR, which became effective in 2018.

Legal Framework: Article 17 GDPR and UK GDPR

2.1 Core Principles of the Right to Erasure

Article 17 of both the EU GDPR and the UK GDPR establishes the fundamental "right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay". This provision serves as the statutory underpinning for what is commonly referred to as the "right to be forgotten." However, it is imperative to understand that this right is not absolute. Organizations are not universally obligated to delete all personal data upon request; rather, the right applies only under specific, defined circumstances, and various exemptions can legitimately justify a refusal to erase data.

The conditional nature of this right is a direct and necessary reflection of the inherent tension between an individual's right to privacy and other fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression, public interest, and legal obligations. An absolute right to erasure would severely impede crucial societal functions, including journalistic freedom, the integrity of historical research, the ability to pursue or defend legal claims, and compliance with statutory record-keeping requirements. Such an unfettered right could effectively lead to the "rewriting of history," undermining the public record and accountability.

This means that the practical implementation of the RTBF is inherently a delicate balancing act for data controllers. It necessitates a nuanced, case-by-case assessment of each request against a defined set of grounds for erasure and applicable exemptions, rather than a simple, automated deletion policy. This complexity underscores the critical need for robust internal policies, well-trained personnel, and meticulous documentation to navigate the legal landscape effectively, ensuring both compliance with data protection laws and the preservation of other fundamental rights.

2.2 Specific Grounds for Invoking the Right to Erasure

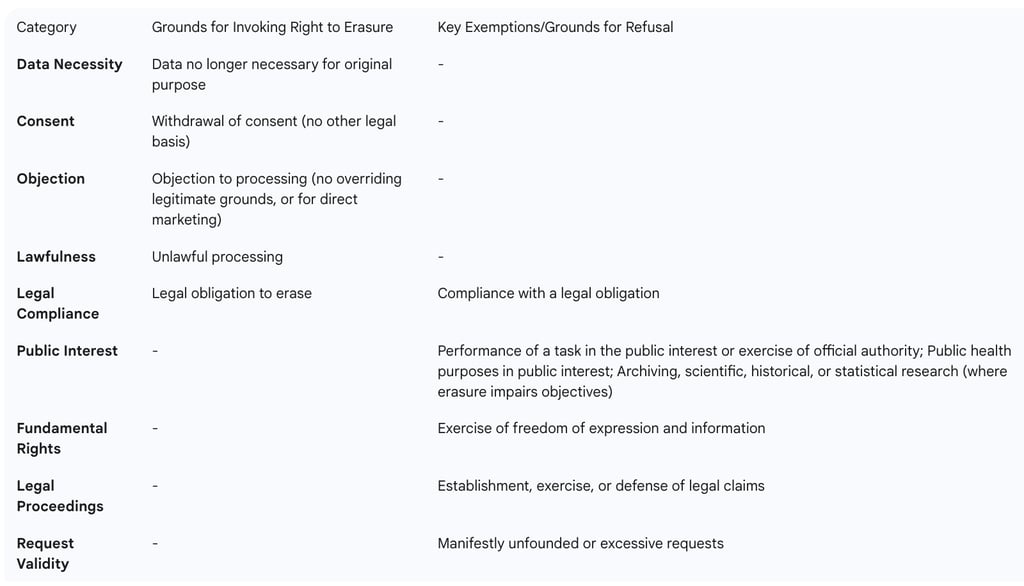

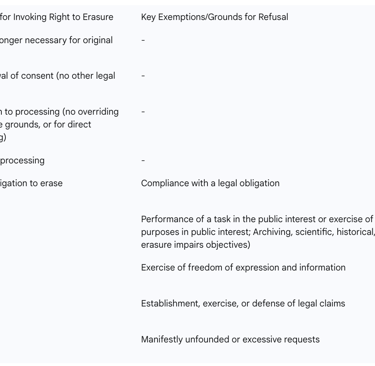

An individual can invoke the right to erasure under Article 17 when one of the following specific grounds applies :

Data no longer necessary: The personal data is no longer required for the purposes for which it was originally collected or subsequently processed. This implies that once the initial, legitimate purpose for data collection has been fulfilled, the data subject may request its removal.

Withdrawal of consent: The processing of the data was based on the individual's explicit consent (e.g., under Article 6(1)(a) or Article 9(2)(a) of GDPR), and they subsequently withdraw that consent. This ground applies provided there is no other independent legal basis that permits the controller to continue processing the data.

Objection to processing: The individual objects to the processing of their personal data pursuant to Article 21(1) (e.g., where processing is based on legitimate interests or public interest) and there are no overriding legitimate grounds for the controller to continue processing. This also applies if the individual objects to the processing for direct marketing purposes (Article 21(2)), in which case the right to erasure is generally absolute.

Unlawful processing: The personal data has been processed unlawfully, meaning it was collected, stored, or used in breach of the lawfulness requirement of the first GDPR principle. This could include situations where data was collected without a valid legal basis or in violation of data minimization principles.

Legal obligation: The controller is subject to a legal obligation under Union or Member State law that explicitly requires the erasure of the personal data. This ensures that GDPR aligns with other national legal frameworks.

Children's data: The personal data has been collected in relation to the offer of information society services directly to a child, as referred to in Article 8(1). There is a particular emphasis on prompt and sensitive handling of erasure requests for children's data, acknowledging that children may not have been fully aware of the risks involved at the time of consent. This heightened protection reflects the vulnerability of minors in the digital environment.

The explicit listing of "withdrawal of consent" as a primary ground for invoking the right to erasure highlights the significant power data subjects retain over their information when consent forms the legal basis for processing. Relying solely on consent for processing personal data inherently carries a higher risk of future erasure requests compared to other legal bases, such as legal obligation, contractual necessity, or legitimate interest. If an organization's processing activities are predominantly consent-based, it must implement exceptionally robust mechanisms for managing consent withdrawal and subsequent data erasure. This includes not only the technical capabilities for deletion but also clear internal policies for determining whether an alternative legal ground for processing exists, which is often not the case once consent is withdrawn. The GDPR's emphasis on "informed consent" and ensuring that withdrawal is "as easy as providing consent" further operationalizes this burden on data controllers. This legal dynamic encourages organizations to strategically and carefully consider their legal bases for data processing from the outset, incentivizing them to choose the most appropriate and durable legal basis for each processing activity, rather than defaulting to consent, which can be easily revoked. This also underscores the critical need for clear, transparent privacy statements and user-friendly mechanisms that empower individuals to manage their consent and data rights effectively.

2.3 Key Exemptions and Grounds for Refusal

Even when a ground for erasure is present, the right is not absolute, and organizations can refuse to comply if one of the following exemptions applies :

Freedom of expression and information: Processing is necessary for exercising the right of freedom of expression and information, particularly for journalistic, academic, artistic, or literary purposes in the public interest.

Legal obligation: The processing is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation that requires processing by Union or Member State law to which the controller is subject (e.g., retaining payroll records under tax law, employee records under employment or health and safety law).

Public interest/Official authority: Processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

Public health: Processing is necessary for reasons of public interest in the area of public health (e.g., protecting against serious cross-border threats to health, or ensuring high standards of quality and safety of healthcare and medicinal products or medical devices). Specific exemptions exist for special category data in this context, especially when processed by a professional subject to a legal obligation of professional secrecy.

Archiving, scientific, historical, or statistical research: Processing is necessary for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes, or statistical purposes, in so far as the right to erasure is likely to render impossible or seriously impair the achievement of the objectives of that processing, provided appropriate safeguards are in place.

Legal claims: Processing is necessary for the establishment, exercise, or defense of legal claims, even if no claim is currently active. This exemption can be relied upon even before a legal claim is filed or threatened, provided there is a potential for such claims (e.g., potential tribunal claims by an employee, or contract disputes).

Requests can also be refused if they are deemed manifestly unfounded or excessive. This is a very high bar to clear, requiring the organization to demonstrate why the request is manifestly unfounded (e.g., the individual clearly has no intention to exercise their right, or the request is malicious in intent and used to harass the organization) or excessive (e.g., it repetitively overlaps with previous requests without new merit). The UK Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018) also adds further, often sector-specific, exemptions beyond those explicitly listed in Article 17 of the UK GDPR.

The broad nature of several exemptions, particularly those related to "public interest," "freedom of expression," and "legal claims," means that their application is not always straightforward and can frequently lead to disputes. The "public interest" clause, especially concerning journalistic, academic, or historical purposes, creates a constant tension and legal battleground between individual privacy rights and societal rights to information and the historical record. The inherent vagueness in defining what precisely constitutes "public interest" means that each case requires a subjective, fact-specific determination. This often leads to challenges and appeals to supervisory authorities or courts, as exemplified by the

Google Spain case itself, which underscored this complex balancing act. The inclusion of "manifestly unfounded or excessive" as a refusal ground further complicates the assessment, requiring controllers to meticulously justify their decisions and meet a high evidentiary standard. This dynamic means that data controllers, particularly those managing public-facing information like search engines or media organizations, must develop sophisticated internal frameworks and often seek specialized legal counsel to navigate these complex assessments. It also highlights the ongoing evolution of case law as courts continue to interpret and refine the boundaries of these rights in the ever-changing digital landscape.

Table 1: Grounds for Invoking and Exemptions to the Right to Erasure (Under GDPR/UK GDPR)

Practical Implementation for Data Controllers

3.1 General Process for Handling Erasure Requests

Organizations are obligated to establish transparent and accessible procedures for individuals to submit erasure requests. These requests can be made verbally or in writing, and do not require specific wording to be valid. Effective procedures should include multiple submission channels, such as online forms, email, or postal mail, and clearly communicate timelines for acknowledging and responding to requests.

Upon receiving a request, the data controller must verify the requester's identity. This involves taking reasonable and proportionate steps to ensure that the individual making the request is indeed the data subject, or has legitimate authority to act on their behalf. This verification step is crucial to prevent unauthorized data deletion and potential security breaches. The request must be actioned "without undue delay," and in any case, within one calendar month of receipt. For particularly complex requests, this deadline can be extended by up to two additional months, provided the individual is informed of the extension and the reasons for it within the initial one-month period.

A critical step in processing an erasure request involves identifying all personal data in scope across all relevant assets. This includes searching customer databases, employee records, marketing lists, CRM systems, backup archives, and data held in cloud storage. The controller must then rigorously determine whether the right to erasure applies based on the specific grounds outlined in Article 17 and assess if any exemptions justify refusal. This decision-making process must be thoroughly documented, providing a clear audit trail for compliance purposes. If a request is refused, the individual must be informed without undue delay and within one month, with clear reasons for the refusal and information on their right to complain to the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) or another supervisory authority, or to seek judicial remedy.

3.2 Technical Measures for Implementation

Effective implementation of the Right to be Forgotten necessitates robust technical capabilities and comprehensive data management strategies. Organizations must first establish strong data governance and management frameworks. This involves meticulously mapping the location, purpose, and consent status of personal data across all their systems. A master data management system can provide a unified view of customer data, enabling precise identification of data points slated for deletion.

Secondly, metadata collection and maintenance are essential. Processes should be established to maintain metadata, including access logs, data relationships, and consent status, which ensures accurate handling of data deletion requests. This metadata helps in tracking data lineage and ensuring that all copies and replicates are identified.

Thirdly, organizations need to implement technical capabilities for data deletion. This includes developing or utilizing systems and applications that allow for easy identification and deletion of individuals' data across all platforms, including live systems, backup systems, and cloud environments. It is important to assess the implications of deletion, as it can impact how different software works. While immediate overwriting in backups may not always be feasible, data in backups must be put "beyond use" and not utilized for any other purpose, simply held until replaced in line with an established schedule. Audit trails should be maintained to document all erasure actions.

Finally, automation can significantly streamline compliance tasks, reducing manual effort and enhancing accuracy. Tools and platforms can be leveraged to automate aspects of data identification, deletion, and notification processes, especially for routine or high-volume requests.

3.3 Notification to Third Parties

A critical obligation for data controllers, particularly when personal data has been shared or made public, is the notification to third parties. Where the controller has made the personal data public and is obliged to erase it, they must take reasonable steps, considering available technology and the cost of implementation, to inform other controllers who are processing the personal data that the data subject has requested the erasure of any links to, or copies or replications of, that data.

This involves maintaining accurate records of where data has been shared and establishing standardized notification methods for informing recipients of erasure requests. All notification efforts should be meticulously documented, and, where possible, confirmation processes should be implemented to verify third-party compliance. If personal data has been disclosed to other recipients, the organization must inform these recipients of the erasure, unless it proves impossible or involves disproportionate effort. Furthermore, if requested by the individual, the organization must also inform them about these recipients. This requirement ensures that the effect of the erasure request extends beyond the initial data controller, promoting a broader adherence to the individual's right to have their data removed from circulation.

Implementation by Search Engines and Online Platforms

4.1 Specific Processes and Challenges

Technology companies, particularly search engines and social media platforms, play a crucial role in the implementation of the Right to be Forgotten, acting as gatekeepers of online information. Their algorithms determine the visibility of content, making their processes central to RTBF compliance.

For search engines like Google, the process for handling RTBF requests involves a careful balance between an individual's right to privacy and the public's right to access lawful information. The process typically begins with an individual submitting a request via an online form, identifying specific URLs they wish to have delisted and providing reasons based on GDPR grounds. Google, for instance, received approximately 3.2 million requests to delist URLs from about 502,000 requesters during the first five years (May 2014 to May 2019), approving about 45% of these.

The review process involves assessing factors such as the requester's role in public life, the nature of the information (e.g., sensitive data receives greater protection), the source of the information (official records are harder to delist), the age of the content, and the balance between the impact on the individual's life versus the public interest in access. Google's review team manually annotates each requested URL with data like site category and content type to aid in this complex decision-making. While initial decision times were lengthy (85 days in 2014), they significantly improved to 6 days by 2019. It is important to note that delisting from search results does not mean the content is erased from the original website.

Technology companies face significant challenges in implementing the RTBF at scale due to the immense volume of data and the complexity of content moderation. Key difficulties include:

Balancing the right to privacy with the right to freedom of expression: This is a constant tension, requiring nuanced judgment on a case-by-case basis.

Developing accurate algorithms: Creating algorithms capable of precisely identifying and removing sensitive or outdated information while avoiding over-censorship is a complex technical hurdle.

Managing algorithmic bias: Algorithms trained on biased data may disproportionately remove content from certain groups, leading to unfair outcomes. Mitigation requires transparent, auditable algorithms, robust testing, and mechanisms for users to appeal decisions.

For social media platforms, individuals often have options for direct content deletion, account deletion, or utilizing platform-specific data request tools (e.g., Facebook's Privacy Center, Twitter's privacy settings). For third-party websites, individuals must contact the site directly, providing necessary information and a legal basis for removal, with a follow-up to national data protection authorities if no response is received within 30 days

4.2 Territorial Scope and Global Implications

A significant aspect of RTBF implementation, particularly for global platforms, is its territorial scope. The European Court of Justice (CJEU) clarified this in the 2019 Google v. Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertes (CNIL) case C-507/17. This ruling established that, under current EU law, there is no obligation for Google and other search engine operators to apply the European Right to be Forgotten globally. This means an EU resident can primarily demand that information related to them be delisted from internet searches conducted within the European Union.

The implications of this territorial limitation are substantial:

Limited Global Enforcement: Despite a court order, personal data of a data subject can still be accessed by anyone outside the European Union or by those within the EU using a non-EU search engine domain, unless effective measures like geo-blocking are implemented. This means that while search results might be delisted for users in EU member states, they could still appear for users accessing search engines from outside the EU or by using virtual private networks (VPNs) to bypass geo-restrictions.

Accessibility via VPNs: The ability of internet users to circumvent geo-blocking measures through VPNs further complicates the practical effectiveness of territorial delisting orders, as de-referenced information can still be accessed.

Need for Universal Enforceability: The fact that personal information remains accessible to internet users outside a data subject's immediate territory highlights a strong argument for an expansion of the territorial nature of the Right to be Forgotten, advocating for it to be universally enforceable.

This situation underscores a fundamental challenge in governing information in a globally interconnected digital environment. While the RTBF aims to protect data subjects' privacy, its implementation faces inherent limitations when confronted with the borderless nature of the internet and the varying legal frameworks across jurisdictions. This necessitates ongoing international cooperation and legal evolution to address the complexities of achieving true "forgetfulness" in a global context.

UK vs. EU GDPR: Post-Brexit Comparison

5.1 Similarities and Divergences

Following the United Kingdom's departure from the European Union, the data protection legal framework bifurcated. While the EU continues to enforce the original GDPR within its member states, the UK adopted its own version, commonly referred to as UK GDPR. The UK GDPR was largely created by incorporating the EU GDPR into UK domestic law, ensuring a high degree of alignment in data protection standards.

Many core principles, rights, and obligations remain consistent between the two frameworks. Both uphold principles such as lawfulness, fairness, transparency, purpose limitation, data minimisation, accuracy, storage limitation, integrity, and confidentiality. Individuals in both jurisdictions retain similar rights, including the right of access, rectification, restriction of processing, data portability, and the right to object, alongside the Right to Erasure (Right to be Forgotten). Both also mandate the appointment of a Data Protection Officer (DPO) for organizations processing large amounts of personal or sensitive data and require Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) for high-risk processing activities.

However, subtle yet significant divergences exist, primarily stemming from the UK's ability to adapt the legislation to its domestic context post-Brexit. These include:

Adapting Legal Frameworks: The UK made minor tweaks, such as removing direct references to the EU and setting a minimum age of consent for information society services at 13 years, compared to the EU GDPR's 16 years.

International Data Transfers: Post-Brexit, the UK is considered a "third country" under EU GDPR. While the EU has granted an adequacy decision for the UK, allowing data to flow freely, this decision is subject to review (e.g., in 2025). The UK also has its own adequacy assessment process for data transfers from the UK to other countries, including EU member states.

Local Representation: Overseas companies handling data from UK residents must now have a representative in the UK.

Regulatory Oversight: The Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) is specified as the relevant authority for UK GDPR enforcement. The UK government has also expressed a desire for more flexibility in areas like national security and immigration, which could lead to more sector-specific exemptions under UK GDPR than exist under EU GDPR.

Penalties: While the structure of fines is similar (up to 4% of global turnover), the maximum monetary amounts differ slightly (£17.5 million in the UK vs. €20 million in the EU).

5.2 Practical Implications for Organizations Operating in Both Jurisdictions

For organizations operating in both the UK and EU, these similarities and divergences create a complex compliance landscape. The primary implication is dual applicability, meaning businesses must comply with two distinct, albeit closely aligned, sets of regulations. This necessitates a thorough understanding of both the EU GDPR and UK GDPR to ensure consistent compliance across all operations.

Data transfers between the UK and EU require careful management. While the current adequacy decision simplifies transfers, organizations must remain vigilant about its potential expiration or changes, which could necessitate the implementation of alternative safeguards such as Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). This adds a layer of administrative burden and legal complexity to international data flows.

Furthermore, the potential for diverging requirements in specific areas, such as consent mechanisms or exemptions related to national security, means that a "one-size-fits-all" approach to data protection policies may not suffice. Organizations need to be prepared to adapt their internal processes and documentation to accommodate any future legislative changes in either jurisdiction. The presence of separate regulatory bodies (the ICO in the UK and various Data Protection Authorities in EU member states) also means that enforcement actions and interpretations may vary, requiring organizations to stay abreast of local guidance and precedents.

Debates, Criticisms, and Future Outlook

6.1 Balancing Rights: Privacy vs. Freedom of Expression

The implementation of the Right to be Forgotten is inherently fraught with tension, primarily due to the fundamental conflict it creates between an individual's right to privacy and the broader right to freedom of expression and information. Proponents emphasize its necessity in empowering individuals to control their digital narratives and prevent outdated or irrelevant information from perpetually impacting their lives. They argue that without this right, individuals face the constant fear of being unexpectedly confronted with their past actions or statements, potentially hindering job seeking, business relations, or personal development.

Conversely, critics, including free speech advocates and historians, argue that a broad application of the RTBF risks unjustifiable censorship and the "rewriting of history". They contend that making it harder to research individuals' pasts inhibits the public's right to full knowledge and access to information, which is crucial for democratic self-governance and accountability. The vagueness in defining what constitutes "inadequate, irrelevant, or excessive" information further complicates this balance, often leading to subjective decisions by private entities (like search engines) that may be ill-equipped to act as arbiters of truth or public interest.

The inherent difficulty lies in drawing a clear line between information that genuinely harms an individual's private life and information that serves a legitimate public interest, such as details about public figures, criminal history, or matters of public concern. Courts and regulatory bodies are continuously engaged in this complex balancing act, with each case requiring a nuanced assessment of the specific circumstances. The ongoing debate highlights that while privacy is a vital right, it must be reconciled with the equally important societal need for accessible information and a verifiable historical record.

6.2 Effectiveness and Limitations

The practical effectiveness of the Right to be Forgotten faces several limitations, particularly with the rapid evolution of technology. One significant concern is the challenge of achieving true erasure in a distributed digital environment. Even if a search engine delists content, the original information often remains on the source website. This means that while discoverability via major search engines is reduced, the data is not completely obliterated from the internet, and could still be found through direct links, specialized searches, or alternative platforms.

The rise of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs) has introduced new complexities, making the concept of being "forgotten" even more challenging. LLMs are trained on massive datasets, including publicly available personal data. Even if specific data is deleted from its original source, AI models may retain learned patterns or infer similar details, making complete "unlearning" impractical without retraining the entire model from scratch—a costly and often infeasible solution for petabyte-scale datasets. The proliferation of AI systems and the unregulated sharing of AI outputs further complicate efforts to trace and remove all instances of "forgotten" information.

Furthermore, the territorial limitations of the RTBF, as established by cases like Google v. CNIL, mean that delisting orders primarily apply within specific geographic regions, such as the EU. This allows information to remain accessible outside these territories or via VPNs, undermining the global impact of the right. Critics also point to the potential for abuse, where individuals, including politicians or criminals, might attempt to erase legitimate but unfavorable aspects of their histories, raising concerns about the integrity of public records. The varying national approaches to the right across jurisdictions also make it difficult for multinational entities to comply consistently.

Academic studies have also highlighted limitations. For instance, research indicates that it is sometimes possible to determine the identity of individuals requesting delisting, and the delisted URLs, particularly on mass-media sites. The RTBF can also impact libraries and archives, potentially leading to the rewriting of the historical record if courts order the deletion or anonymization of content from digital archives. This also poses challenges for scholarly research, as delisted links in general search engines could extend to academic databases, hindering discoverability of relevant information.

6.3 Enforcement and Penalties

Enforcement of data protection regulations, including the Right to be Forgotten, is primarily handled by national data protection authorities (DPAs) in their respective jurisdictions. In the UK, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) serves as the independent supervisory authority responsible for enforcing the UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018.

These authorities possess significant powers to ensure compliance and can levy substantial administrative fines on organizations found to be in violation. Both the GDPR and UK GDPR establish a two-tiered system for administrative fines :

Lower Tier: Up to €10 million (or £8.7 million in the UK) or 2% of the annual global turnover, whichever is higher, for less serious infringements, such as violations of administrative requirements or obligations related to child's consent or data processing without identification.

Higher Tier: Up to €20 million (or £17.5 million in the UK) or 4% of the total annual worldwide turnover, whichever is higher, for more serious infringements. This applies to violations of core data protection principles, individuals' rights, sensitive data processing, consent requirements, and international data transfers.

The calculation of turnover for fines considers the entire corporate group, meaning a parent company's global turnover can be used as the benchmark, not just that of an individual subsidiary. DPAs have discretion in determining whether to impose a fine and its amount, considering factors such as the nature, gravity, and duration of the infringement, intent or negligence, mitigation steps, precautions in place, history of previous infringements, cooperation with authorities, the type of data involved, and notification procedures.

The ICO, for instance, issues various enforcement actions, including monetary penalties, reprimands, and enforcement notices, and can also pursue prosecutions. Recent examples of ICO enforcement include significant fines for security failures, unlawful direct marketing calls, and failures to respond to subject access requests within statutory timeframes. These penalties underscore the financial liability organizations face for non-compliance, making robust data protection practices a critical priority globally.

Conclusion

The implementation of the Right to be Forgotten, primarily codified as the Right to Erasure under GDPR and UK GDPR, represents a complex and evolving area of data protection law. Originating from the landmark Google Spain judgment, this right empowers individuals to seek the removal or delisting of their personal data under specific conditions. However, its application is not absolute, necessitating a careful balancing act between individual privacy rights and other fundamental considerations such as freedom of expression, public interest, and legal obligations.

For data controllers, effective implementation requires establishing transparent procedures for handling requests, robust technical capabilities for data identification and deletion across all systems (including backups), and a diligent protocol for notifying third parties. The nuanced distinction between delisting (RTBF) and complete erasure is critical for compliance. Search engines and online platforms, acting as de facto arbiters of online information, face unique technical and ethical challenges in balancing these competing rights, particularly in developing unbiased algorithms and managing vast volumes of data.

The post-Brexit landscape has introduced a dual regulatory environment with UK GDPR mirroring EU GDPR, yet with subtle divergences in areas like age of consent and international data transfers. This requires organizations operating across both jurisdictions to navigate a complex, albeit largely harmonized, compliance framework.

Despite its intent to empower individuals, the effectiveness of the Right to be Forgotten is subject to ongoing debate. Criticisms persist regarding its potential for censorship, the practical limitations of achieving complete digital oblivion in a globally interconnected internet, and the new challenges posed by generative AI. The territorial scope of delisting orders further limits its global reach, highlighting the need for international cooperation to address the borderless nature of digital information.

Ultimately, the Right to be Forgotten is a testament to the ongoing effort to define and protect privacy in the digital age. Its continued evolution will depend on judicial interpretations, technological advancements, and the collective commitment of regulators, organizations, and individuals to strike a sustainable balance between the right to be forgotten and the enduring value of accessible information and historical record.

Monitoring, Measuring and Improving RTBF Compliance

Compliance Metrics and KPIs

Organizations should establish robust metrics to monitor RTBF compliance effectiveness:

Request Processing Metrics: Track key performance indicators such as request volumes, processing times, completion rates, and exception percentages to identify trends and potential compliance gaps. Regular reporting on these metrics to privacy governance committees enables ongoing program evaluation.

Quality Assurance Sampling: Implement regular quality assurance reviews of completed erasure requests, randomly sampling cases to verify proper handling, documentation, and complete execution across systems. These reviews can identify process weaknesses before they become compliance issues.

Cost and Resource Tracking: Monitor resources devoted to RTBF compliance, including staff time, technology investments, and third-party costs. This tracking enables cost-benefit analysis and more efficient resource allocation over time.

Regulatory Engagement Metrics: Track interactions with data protection authorities regarding erasure requests, including inquiries, complaints, and resolution outcomes. These metrics provide valuable insights into regulatory expectations and potential areas for improvement.

Continuous Improvement Processes

Effective RTBF implementation requires ongoing refinement and adaptation:

Regular Policy and Process Reviews: Schedule periodic reviews of RTBF policies, procedures, and technical implementations to identify improvement opportunities and ensure alignment with evolving regulatory guidance and case law. These reviews should occur at least annually and after significant regulatory developments.

Feedback Integration Systems: Establish mechanisms to collect feedback from individuals making erasure requests, staff processing requests, and technical teams implementing erasure. This multifaceted feedback provides valuable insights for process refinement.

Regulatory Monitoring Program: Develop a systematic approach to monitoring regulatory guidance, enforcement actions, and court decisions related to the Right to Be Forgotten. This monitoring enables proactive adaptation to evolving interpretations.

Tabletop Exercises and Simulations: Conduct regular scenario-based exercises to test RTBF response capabilities, especially for complex or unusual request types. These exercises identify process weaknesses in a controlled environment where they can be addressed without compliance consequences.

Leveraging Technology for Compliance Improvement

Advanced technologies can significantly enhance RTBF compliance capabilities:

AI and Machine Learning Tools: Implement AI-powered solutions to improve data discovery, classification, and mapping. These tools can identify previously unknown or unclassified personal data repositories and improve erasure completeness.

Blockchain for Compliance Records: Consider blockchain technology for maintaining tamper-proof records of erasure requests and actions taken, providing immutable evidence of compliance efforts while protecting the privacy of requesters.

Privacy Enhancing Technologies: Explore emerging privacy-enhancing technologies such as federated learning, homomorphic encryption, and distributed privacy systems that can reduce compliance burdens by minimizing unnecessary data collection and storage.

Automation of Compliance Workflows: Invest in automation technologies that can reduce manual handling of erasure requests, improving consistency, reducing human error, and accelerating processing times while maintaining appropriate human oversight for complex cases.

Future Trends and Evolving Compliance Landscape

Regulatory Evolution

The regulatory landscape governing the Right to Be Forgotten continues to evolve:

Global Expansion of Erasure Rights: The concept of data erasure rights is expanding beyond Europe, with similar provisions appearing in regulations worldwide, including Brazil's LGPD, California's CCPA/CPRA, and other emerging privacy frameworks. Organizations should monitor this global expansion and adapt compliance programs accordingly.

Regulatory Harmonization Efforts: Initiatives to harmonize data protection approaches across jurisdictions may simplify compliance for global organizations but will require careful monitoring and adaptation as new frameworks emerge. Participating in industry associations can provide early insights into harmonization trends.

Enforcement Trends: Data protection authorities are increasingly focusing on effective implementation of data subject rights, including the Right to Be Forgotten. Organizations should monitor enforcement actions and penalties to understand regulatory priorities and compliance expectations.

Sector-Specific Guidance: Regulators are developing more granular, sector-specific guidance on RTBF implementation, acknowledging the unique challenges in different industries. Organizations should engage with these developments through industry associations and regulatory consultations.

Technological Developments

Emerging technologies are reshaping both the challenges and opportunities in RTBF compliance:

Artificial Intelligence and Automated Decision-Making: As AI systems become more prevalent, erasure rights will need to extend to personal data used for algorithmic training and decision-making, presenting novel implementation challenges. Organizations should develop specific approaches for managing erasure requests related to AI systems.

Decentralized Data Architectures: The rise of decentralized technologies and edge computing creates new complexities for data erasure. Organizations adopting these architectures should design erasure capabilities from inception rather than retrofitting compliance later.

Privacy-Preserving Computation: Technologies enabling data analysis without data exposure, such as secure multi-party computation and trusted execution environments, may reduce erasure complexities by limiting data proliferation. Organizations should explore these technologies as part of long-term compliance strategies.

Quantum Computing Implications: In the longer term, quantum computing may create both threats to current data protection mechanisms and opportunities for more sophisticated privacy protections. Organizations should monitor these developments and incorporate quantum considerations into future compliance planning.

Strategic Positioning

Forward-thinking organizations are transforming RTBF compliance from a regulatory burden to a strategic advantage:

Privacy as a Competitive Differentiator: Organizations that implement superior erasure capabilities can position privacy respect as a competitive advantage, building trust with privacy-conscious consumers and business partners. This positioning should be integrated into broader brand and marketing strategies.

Data Minimization Culture: Leading organizations are moving beyond compliance to embrace data minimization as a core principle, reducing RTBF compliance burdens while simultaneously decreasing data security risks and storage costs. This cultural shift requires executive sponsorship and cross-organizational engagement.

Proactive Relationship Management: Rather than treating erasure requests as adversarial, progressive organizations view them as opportunities to enhance customer relationships through responsive, transparent handling. This approach transforms compliance from a cost center to a relationship-building opportunity.

Privacy Innovation Leadership: Organizations at the forefront of RTBF compliance are contributing to the development of industry standards, technologies, and best practices, positioning themselves as thought leaders while ensuring regulatory frameworks reflect operational realities. Engagement with standards bodies and industry associations enables this leadership positioning.

FAQ

What exactly is the Right to Be Forgotten under GDPR?

The Right to Be Forgotten (also called the right to erasure) is established in Article 17 of the GDPR. It gives individuals the right to request deletion of their personal data when certain conditions are met, such as when data is no longer necessary, consent is withdrawn, or there's no legitimate interest for continued processing.

Can organizations refuse a Right to Be Forgotten request?

Yes, organizations can refuse RTBF requests when specific exemptions apply. These include processing necessary for freedom of expression, legal obligations, public interest tasks, public health purposes, scientific/historical research, or the establishment of legal claims.

How quickly must organizations respond to erasure requests?

Under GDPR, organizations must respond to erasure requests "without undue delay" and within one month of receipt. This period may be extended by up to two additional months for complex requests, provided the individual is informed of the extension within the first month.

What are the biggest technical challenges in implementing RTBF?

The major technical challenges include: locating all instances of personal data across systems; handling erasure in backup and archive systems; managing data interdependencies; coordinating deletion across distributed architectures; and ensuring complete verification of erasure across all systems.

How should organizations handle RTBF requests that conflict with legal retention requirements?

When legal retention requirements conflict with erasure requests, organizations should document the specific legal basis for retention, restrict access to the retained data, implement data isolation techniques, and clearly explain to the individual why complete erasure isn't possible and how long the data must be retained.

Do RTBF obligations extend to third-party processors?

Yes, RTBF obligations extend to third-party processors. Organizations must inform all processors handling the relevant personal data about erasure requests and ensure they comply with the erasure requirements. This should be covered in data processing agreements with all processors.

What documentation should organizations maintain for RTBF requests?

Organizations should document receipt of requests, identity verification procedures, assessment of whether RTBF applies, actions taken to implement erasure, justifications for any refusals, communications with the individual, and verification of erasure completion across all relevant systems.

How does the Right to Be Forgotten differ across jurisdictions?

While GDPR provides the most comprehensive RTBF framework, similar rights exist in other privacy regulations with varying scopes and limitations. Organizations operating globally must understand these differences and implement jurisdiction-specific processes while maintaining a consistent overall approach.

What steps should an organization take when first implementing RTBF compliance?

Key initial steps include: conducting data mapping to identify where personal data resides; developing formal RTBF policies and procedures; creating request intake systems; establishing identity verification protocols; implementing technical erasure capabilities; training staff; and establishing monitoring mechanisms.

How can organizations verify that data has been completely erased across all systems?

Verification requires systematic processes including confirmation checks across all identified data repositories, automated verification tools, post-erasure search testing, third-party processor confirmations, and comprehensive documentation of verification steps to demonstrate due diligence.

Additional Resources

For readers seeking more in-depth information on RTBF implementation, the following resources provide valuable guidance:

European Data Protection Board (EDPB) Guidelines on the Right to Erasure: Comprehensive regulatory guidance on interpreting and implementing Article 17 of the GDPR, including case studies and practical examples.

"Implementing the Right to Be Forgotten: Technical Approaches and Challenges" (International Association of Privacy Professionals): A technical whitepaper exploring architectural and system design considerations for effective erasure capabilities.

ISO/IEC 27701:2019 – Privacy Information Management: International standard providing guidance on implementing privacy controls, including erasure mechanisms, within information security management systems.

"GDPR Implementation and Compliance Handbook" (Datasumi Compliance Advisory): A practical guide to GDPR implementation with significant coverage of data subject rights including the Right to Be Forgotten. Visit Datasumi Compliance Advisory for more information.

"Balancing Privacy Rights with Competing Obligations: A Legal Framework" (International Review of Law and Technology): Academic analysis of approaches to reconciling erasure rights with other legal and ethical considerations.