The Right to Object Under GDPR: Empowering Businesses and Protecting Data Subjects

Discover the Power of Personal Information in the Digital Age! Safeguarding your data has never been more vital as it transforms into a valuable resource for businesses across all sectors.

Among the eight fundamental rights granted to individuals under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Right to Object, enshrined in Article 21, stands as a critical instrument of data subject autonomy. It serves as a powerful check on a data controller's activities, particularly when the legal justification for processing personal data is not derived from the individual's explicit consent. This right fundamentally alters the traditional power dynamic, empowering a data subject to challenge and, in certain circumstances, halt the processing of their personal data based on their unique and "particular situation".

The significance of Article 21 extends beyond individual empowerment; it imposes a framework of accountability on businesses (data controllers). By choosing to process data on grounds such as 'legitimate interests', a business gains operational flexibility but simultaneously accepts that this processing is subject to a potential veto by the very individuals whose data is being used. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of this pivotal right, examining its legal architecture, its practical application, and its interplay with the broader data protection ecosystem. The analysis is designed to serve a dual purpose: to equip businesses and their compliance professionals with the nuanced understanding required to navigate their obligations confidently and to clarify for data subjects the full scope and power of the rights they possess.

Deconstructing Article 21: A Paragraph-by-Paragraph Legal Analysis

A meticulous examination of the legal text of Article 21 of the GDPR reveals the precise mechanics and conditions of this right.

Article 21(1) establishes the qualified right to object. It states that a data subject has the right to object at any time, on grounds "relating to his or her particular situation," to processing based on Article 6(1)(e) (public interest/official authority) or Article 6(1)(f) (legitimate interests). This paragraph introduces the critical concepts of the individual's specific circumstances as the basis for an objection and the controller's corresponding ability to override the objection by demonstrating "compelling legitimate grounds". This provision also explicitly covers profiling based on these legal grounds.

Article 21(2) and 21(3) codify the absolute right to object. Where personal data is processed for direct marketing purposes, the data subject has an unconditional right to object at any time. Article 21(3) reinforces this by stating that upon such an objection, the personal data "shall no longer be processed for such purposes." This right is unequivocal, and the controller has no grounds for refusal. The scope includes any profiling related to direct marketing.

Article 21(4) outlines the controller's proactive notification duty. The right to object must be "explicitly brought to the attention of the data subject and shall be presented clearly and separately from any other information" at the latest by the time of the first communication. This requirement for clear and separate notification is a common point of compliance failure.

Article 21(5) provides a modernization clause, allowing data subjects to exercise their right to object by "automated means using technical specifications" in the context of information society services (e.g., online services).

Article 21(6) creates a specific, more limited version of the right when personal data is processed for scientific or historical research or statistical purposes pursuant to Article 89(1). While an individual can still object based on their particular situation, the right does not apply if the processing is "necessary for the performance of a task carried out for reasons of public interest".

The Interplay with Lawful Bases for Processing (Article 6)

The applicability of the Right to Object is not universal; it is a direct consequence of the controller's foundational choice of lawful basis for processing under Article 6 of the GDPR. This strategic decision creates a fundamental trade-off. If a controller chooses 'legitimate interests' (Article 6(1)(f)), they gain flexibility by not needing to obtain and manage consent, but they simultaneously grant data subjects a powerful, situation-specific veto in the form of the qualified right to object. This means that compliance with Article 21 begins with the strategic decisions made under Article 6. A failure to correctly identify, document, and justify the lawful basis creates a domino effect, rendering any subsequent handling of an objection legally unsound.

The right is specifically triggered when processing is based on one of two lawful bases:

Article 6(1)(e): Public Interest or Official Authority: Processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

Article 6(1)(f): Legitimate Interests: Processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject.

Conversely, the right to object does not apply when processing is based on other lawful grounds. For instance, if processing is based on Article 6(1)(a) - Consent, the data subject's equivalent power is the right to withdraw that consent at any time. Similarly, the right does not apply to processing necessary for the performance of a contract (Article 6(1)(b)), for compliance with a legal obligation (Article 6(1)(c)), or to protect vital interests (Article 6(1)(d)).

The proactive notification requirement in Article 21(4) represents a frequently overlooked compliance trap. Many organizations submerge information about this right within a dense, lengthy privacy policy, which fails to meet the standard of being presented "clearly and separately from any other information". A compliant approach, particularly in initial communications like a welcome email, would involve a distinct, clearly signposted section or statement about this right. This procedural requirement is a straightforward area for regulators to identify non-compliance. A failure to adhere to it can signal a systemic disregard for data subject rights, potentially inviting greater scrutiny from a Data Protection Authority (DPA) should a complaint arise.

The Dichotomy of the Right: Absolute vs. Qualified Objections

Article 21 creates a clear distinction between two forms of the right to object, each with different requirements for the data subject and different obligations for the controller. Understanding this dichotomy is fundamental to compliance.

The Absolute Right: Halting Direct Marketing and Profiling

The most powerful and straightforward form of this right is the absolute right to object to the processing of personal data for direct marketing purposes. This right is unconditional, meaning a controller cannot refuse the request under any circumstances. There is no balancing test to perform, and the controller cannot claim "compelling legitimate grounds" to continue the processing.

Scope and Definition: The GDPR defines direct marketing as any action by a company to communicate advertising or marketing material to particular individuals. The right to object explicitly includes "profiling to the extent that it is related to such direct marketing". This is a critical point, as it prevents organizations from separating the analysis of customer behavior from the targeted advertising that results from it. If profiling is used to inform direct marketing, it falls under this absolute right.

Controller's Obligation: Upon receiving an objection to direct marketing, the controller must cease processing for these purposes "without undue delay". The data subject is not required to provide any reason or justification for their objection.

Practical Implementation: Suppression Lists: While the processing must stop, this does not automatically necessitate the complete erasure of the individual's data. A widely accepted best practice is for the organization to move the individual's details to a "suppression list". This list contains just enough information (e.g., name and email address) to ensure that the individual is not contacted again, especially if the company acquires new marketing lists from third parties in the future. This act of storing data on a suppression list is, paradoxically, a form of processing that is necessary to honor the original objection.

The definition of "direct marketing" can be a compliance minefield. A business might conduct analytics on user behavior to improve its services, an activity it may justify under 'legitimate interests' and which would be subject to a qualified objection. However, if those same analytics are used to personalize advertisements, the activity becomes direct marketing profiling, subject to an absolute objection. The line is often blurry. A business that incorrectly applies the qualified right's balancing test to what is legally direct marketing profiling commits a clear violation of Article 21(3). This necessitates that businesses meticulously map their data flows and be prepared to defend precisely where "service improvement" ends and "direct marketing" begins.

The Qualified Right: Objecting on Grounds of a "Particular Situation"

The second form is the qualified right, which applies when processing is based on the lawful bases of legitimate interests or the performance of a public task/exercise of official authority.

The "Particular Situation" Requirement: Unlike the absolute right, the data subject must provide specific grounds for their objection that relate to their "particular situation". This requires the individual to articulate why the processing has a specific, unwarranted, and negative impact on them. The objection carries more weight if the individual can demonstrate that the processing is causing them "substantial damage or distress," such as financial loss or reputational harm.

The Controller's Response: Once a reasoned objection is received, the controller's burden of proof begins. They are obligated to cease the processing unless they can successfully demonstrate one of two things:

"Compelling legitimate grounds" for the processing which override the interests, rights, and freedoms of the individual. This is a high threshold and is the subject of detailed analysis in the next section.

The processing is necessary for the "establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims".

The "particular situation" requirement can create a communication challenge. The onus is on the data subject to articulate their grounds, but many individuals may lack the legal or technical sophistication to do so effectively. Conversely, some controllers may interpret this requirement too restrictively, dismissing objections that are not framed in precise legal terms, a problem noted by privacy advocates. This can lead to an impasse and a complaint to a DPA. A best practice for businesses is to facilitate this dialogue. If an objection is vague, the controller should consider asking clarifying questions to better understand the individual's concerns, an approach that aligns with the GDPR's principle of facilitating data subject rights under Article 12(2) and can turn a potential conflict into a constructive resolution.

The Special Case: Objections to Processing for Research and Statistical Purposes

A distinct set of rules applies when personal data is processed for scientific or historical research, or statistical purposes under the safeguards of Article 89(1). In this context, an individual can still exercise their qualified right to object on grounds relating to their particular situation. However, the controller is provided with a specific exemption not available in other contexts: they may be able to refuse the request if the processing is deemed "necessary for the performance of a task carried out for reasons of public interest". This creates a higher bar for the data subject's objection to succeed in these specific research scenarios.

The Controller's Crucible: Assessing "Compelling Legitimate Grounds"

When a data controller receives a qualified objection under Article 21(1), they are faced with a critical decision-making process. They must cease processing unless they can meet the high threshold of demonstrating "compelling legitimate grounds" that override the individual's rights. This is not a simple check-box exercise but a nuanced legal and ethical assessment that lies at the heart of the qualified right.

The Balancing Test: A Framework for Decision-Making

The core of the assessment is a balancing test. In essence, the controller must re-conduct their initial Legitimate Interests Assessment (LIA), but this time with a new, significant factor on the scales: the specific, articulated harm or negative impact described by the data subject in their "particular situation". The controller bears the full burden of proof to demonstrate that their grounds for continuing the processing are more compelling than the individual's reasons for stopping it.

The test requires a careful weighing of the controller's interests against the "interests, rights and freedoms of the data subject". Factors to consider, drawing from regulatory guidance, include the nature and importance of the controller's interest, the necessity of the processing to achieve that interest, and the reasonable expectations of the individual alongside the potential impact of the processing on them.

Defining "Compelling": An Analysis of Regulatory Guidance from the EDPB and ICO

The term "compelling" is deliberately set at a higher standard than the simple "legitimate" interest required to begin processing in the first place. Regulatory bodies across Europe have provided guidance that progressively clarifies this high bar.

UK Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) Guidance: The ICO advises that the weight of an objection increases significantly if the individual can show the processing is causing them "substantial damage or distress". The controller must then be able to provide a clear and strong justification for why its needs are more compelling.

European Data Protection Board (EDPB) Guidance: The EDPB has set an even more stringent standard. In its draft guidelines, the EDPB suggests that "compelling" interests must be "essential" to the controller. The primary example provided is processing that is necessary to protect the controller or its systems from "serious immediate harm or from a severe penalty which would seriously affect its business".

This interpretation is transformative. It suggests that the standard for overriding an objection is evolving towards an "existential threat" test. The guidance moves beyond a simple cost-benefit analysis and implies that the processing must be almost fundamentally necessary for the controller's core operations or security to continue against the individual's will. This has profound implications for businesses that rely on 'legitimate interests' for data-intensive activities like algorithmic model training, broad-scale analytics, or product personalization (where it does not constitute direct marketing). If the only way to override an objection is to prove that the business would be severely harmed without that specific individual's data, the qualified right to object becomes nearly absolute in practice for many common business activities.

Practical examples where compelling grounds might exist often involve wider public or legal interests. For instance, a hospital processing patient data for critical public health research, such as measuring the community impact of a virus, may have compelling grounds that override an individual's objection. Similarly, an insurance company processing data as part of mandatory anti-fraud or anti-money laundering measures may be able to demonstrate compelling grounds rooted in legal compliance and public security.

Case Law and Precedent: When do a Controller's Interests Override an Individual's Rights?

While specific case law on "compelling legitimate grounds" is still developing, several key decisions from Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) and courts provide important context.

The Dutch Tennis Association Case (CJEU): In a foundational ruling, the Court of Justice of the European Union confirmed that "commercial" interests can indeed be "legitimate." However, it reinforced that this does not give them automatic precedence; they must still be balanced against the rights of the individual. This principle underpins the entire balancing test.

The TIM S.P.A. Case (Italian DPA): This case serves as a powerful cautionary tale. The Italian telecommunications company was fined a staggering €27.8 million for a range of violations, a core component of which was its systemic failure to honor objections to direct marketing. While this case relates to the absolute right, it demonstrates the severe financial and reputational consequences of failing to respect Article 21.

Search Engine Delisting Cases (Irish DPA): In a case involving a Lithuanian national, the Irish DPA investigated a search engine that refused to delist links to articles containing inaccurate information about past criminal charges. The search engine argued that the individual's former role as a public official made the information a matter of public interest. However, the DPA found that the search engine had failed to properly examine the facts—the individual had been acquitted of the charges. The DPA ruled that the search engine's assumed "public interest" was not compelling when the underlying data was inaccurate and ordered the delisting. This case underscores that the burden of proof is active; the controller must investigate and verify its grounds, not merely assert them.

The obligation for a controller to "demonstrate" compelling grounds is not just a legal argument but an evidentiary one. It implies the existence of documented proof. This connects directly to the necessity of conducting and maintaining a robust Legitimate Interests Assessment (LIA) before processing begins. When an objection is received, the controller is not creating a justification from scratch; they are re-evaluating their pre-existing, documented LIA in light of the new information provided by the data subject. Without a well-reasoned LIA, any attempt to demonstrate compelling grounds will appear ad-hoc, self-serving, and is highly unlikely to withstand regulatory scrutiny. Therefore, a failure to conduct a proper LIA at the outset effectively cripples the controller's ability to legally refuse a qualified objection later.

The Legal Claims Exemption: Scope and Application

The second, and more clear-cut, basis for refusing a qualified objection is when the processing is necessary for the "establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims". This exemption is crucial for managing legal risk and is not limited to active court proceedings. It can also apply to imminent legal action or out-of-court proceedings. However, a vague or speculative possibility of a future dispute is not sufficient to invoke this exemption. This provision is of particular importance in sectors like insurance and finance for fraud prevention and in the context of employment for handling internal investigations, grievances, or potential litigation.

Operationalizing Compliance: A Business's Procedural Handbook

Effective compliance with Article 21 is not merely a matter of legal interpretation but of robust operational readiness. A controller can make the correct substantive decision but still be found in breach due to procedural missteps. Many enforcement actions by DPAs stem from such failures: missing deadlines, creating cumbersome request processes, or demanding excessive identification. Therefore, having trained staff, clear internal policies, and streamlined workflows is not just "good practice" but a core component of legal compliance.

From Receipt to Resolution: Managing the Objection Lifecycle

A structured process is essential for handling objections consistently and defensibly.

Recognition: Staff, particularly in customer-facing, marketing, and HR roles, must be trained to recognize an objection request. The request can be made verbally or in writing and does not need to use the words "GDPR," "objection," or "Article 21" to be valid.

Recording: An internal system or log must be used to record all requests, including the date of receipt, the nature of the objection, and the deadline for response. This creates a vital audit trail for demonstrating accountability.

Identity Verification: A controller may only request additional information to verify an individual's identity if it has "reasonable doubts". This must not be an automatic hurdle. The case against Airbnb, where it demanded photo ID from a user who had never provided one before to process a deletion request, serves as a key example of disproportionate verification and a violation of the data minimization principle.

Communication: Best practice dictates acknowledging receipt of the request promptly and keeping the data subject informed of the status, especially if an extension is needed.

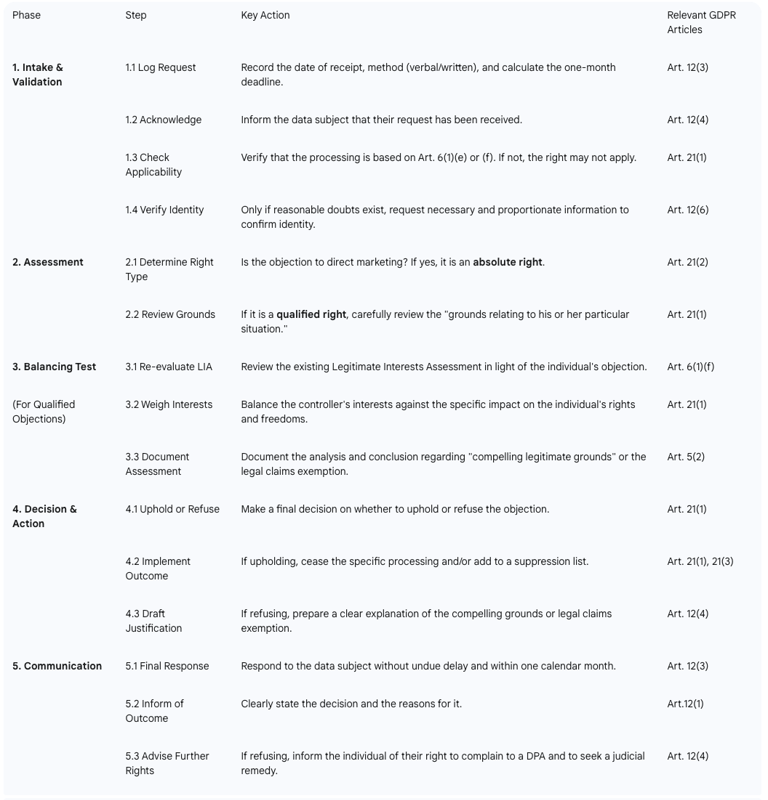

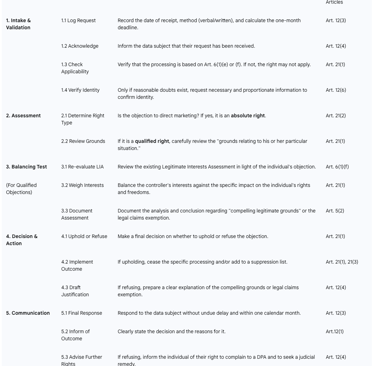

The following checklist provides an actionable workflow for compliance teams, translating complex legal duties into a clear operational guide.

Timelines and Extensions: Adhering to Strict Deadlines

The GDPR imposes a strict timeline for responding to an objection. The controller must act "without undue delay and at the latest within one month of receipt". It is crucial to note that this is a calendar month, not 30 days. For example, a request received on March 31 must be answered by April 30. If a request is received on January 31, the deadline is February 28 (or 29 in a leap year).

This one-month period can be extended by a further two months if the request is particularly complex or if the individual has submitted multiple requests. However, the controller must inform the individual of this extension and the reasons for the delay within the initial one-month period.

Handling "Manifestly Unfounded or Excessive" Requests

In very limited circumstances, a controller can refuse to act on a request or charge a reasonable administrative fee if the request is "manifestly unfounded or excessive". The burden of proof to demonstrate this lies entirely with the controller.

Manifestly Unfounded: This applies when the individual has no genuine intention of exercising their right (e.g., offering to withdraw the request in exchange for a benefit) or when the request is malicious and designed purely to cause harassment or disruption. Examples include making unsubstantiated accusations against staff or systematically sending requests as part of a disruptive campaign.

Excessive: This typically applies to requests that are repetitive in substance or overlap with other requests from the same individual. However, a request is not automatically excessive simply because it repeats a previous one, especially if the controller handled the initial request improperly.

This exemption must be applied on a case-by-case basis and cannot be a blanket policy. The controller must provide a full justification for its decision to the individual.

Post-Objection Data Handling: Suppression vs. Erasure

A successful objection requires the controller to stop processing the data for the purpose to which the individual objected. The subsequent action—suppression or erasure—is a strategic risk management decision.

Erasure involves deleting the data entirely.

Suppression involves retaining a minimal amount of data (e.g., an email address) on a dedicated list to ensure the objection is respected in the future.

For direct marketing objections, suppression is often the more prudent choice. Completely erasing a record creates the risk that the individual's data could be lawfully re-acquired from a third-party source, leading to accidental re-contacting and a new, more serious complaint. In this scenario, the continued processing (storage for suppression) is necessary to comply with the spirit of the original objection. This highlights a nuanced reality of compliance: an action that seems to best align with one GDPR principle (e.g., data minimisation via erasure) could increase the risk of violating another (honoring the right to object). Businesses must document their rationale for choosing suppression over erasure in these contexts. For other types of qualified objections, the data may need to be retained for other lawful purposes not covered by the objection, in which case only the specific processing activity must cease.

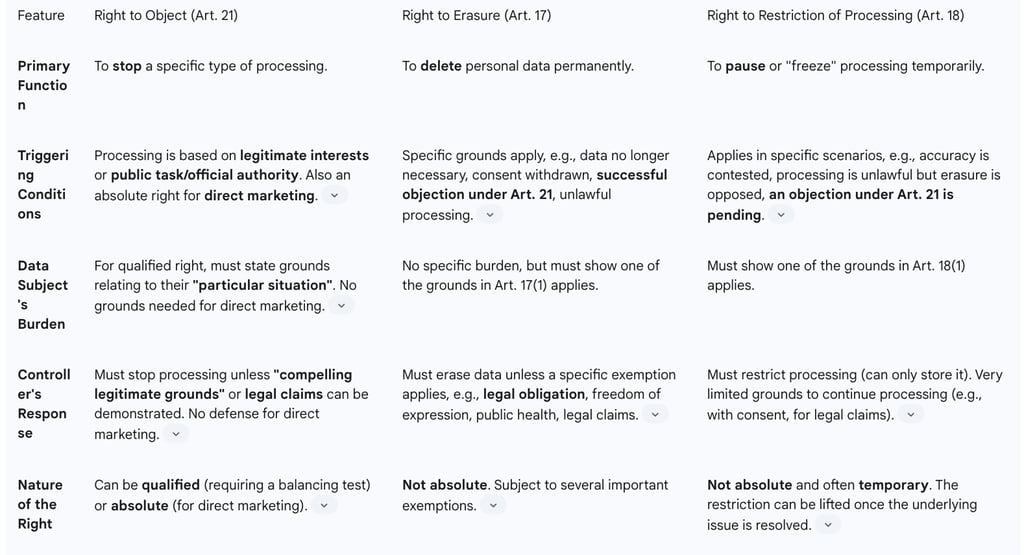

The Broader Rights Ecosystem: Object, Erase, or Restrict?

The Right to Object does not exist in a vacuum. It is part of an interconnected ecosystem of data subject rights under the GDPR. Understanding the interplay between the Right to Object (Article 21), the Right to Erasure (Article 17), and the Right to Restriction of Processing (Article 18) is crucial for both controllers, who must respond to requests correctly, and data subjects, who can use these rights in combination.

A Comparative Analysis: Right to Object (Art. 21), Right to Erasure (Art. 17), and Right to Restriction (Art. 18)

These three rights are distinct in their triggers, outcomes, and the defenses available to a controller. A data subject might ask to be "forgotten" (erasure) when they really mean they object to a specific use, or a controller might incorrectly erase data when only a temporary restriction was requested. The following table provides a comparative analysis to demystify these rights.

Strategic Application: How Data Subjects Can Combine Rights for Maximum Effect

A sophisticated data subject, or a representative acting on their behalf, can strategically combine these rights to maximize their control over their data. Controllers must anticipate these combined requests to ensure a compliant response.

The "Pause and Challenge" Combination: A data subject can submit a qualified objection under Article 21. Simultaneously, they can exercise their Right to Restriction of Processing under Article 18, on the grounds that an objection is pending verification. This creates a powerful combination: the controller is legally obligated to "freeze" the contested data and halt its use while it conducts the one-month balancing test to assess the objection. This prevents the controller from continuing to process the data during the deliberation period.

The "Stop and Delete" Combination: If a data subject's objection under Article 21 is successful, this success itself becomes a valid legal ground to demand erasure. Article 17(1)(c) explicitly grants the right to erasure where "the data subject objects to the processing pursuant to Article 21(1) and there are no overriding legitimate grounds for the processing". Therefore, a successful objection can be immediately followed by a request for erasure, transforming the "stop processing" outcome into a "delete data" outcome.

The Right to Restriction is not merely an alternative to erasure; it is a critical procedural tool that gives teeth to the Right to Object. The explicit right to request restriction while a controller verifies its legitimate grounds has significant operational implications. It means a business cannot simply continue processing as usual while it deliberates. It must have the technical and organizational capacity to "quarantine," "flag," or otherwise isolate the relevant data to prevent its use. This requires systems that can handle a "restricted" status, which is functionally different from "active" or "deleted." A failure to have such a system in place means a business cannot comply with Article 18, even if it is correctly handling the Article 21 objection itself.

Enforcement in Practice: Lessons from Regulatory Actions

The true impact of any legal right is measured by its enforcement. While the GDPR has been in effect for several years, the enforcement landscape surrounding Article 21 is complex and varies significantly across the European Union. Analysis of DPA actions reveals key trends, priorities, and some surprising gaps.

Analysis of Fines and Reprimands Related to Article 21 Violations

Several high-profile cases, while not always citing Article 21 exclusively, are directly relevant to the principles of the Right to Object.

Key Trends in ICO and EU DPA Enforcement Priorities

Analysis of DPA reports and case studies reveals several important trends for businesses to consider.

The ICO's Focus on PECR for Marketing: In the UK, a significant portion of fines related to unwanted marketing are issued under the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR) rather than the GDPR. While these cases are about unlawful electronic marketing, they are intrinsically linked to the spirit of Article 21, as they concern the failure to respect individuals' choices about being marketed to.

Public Sector Leniency: The ICO has a stated policy of generally issuing reprimands and enforcement notices to public sector bodies instead of monetary fines, with the goal of avoiding the diversion of public funds. This has drawn criticism from privacy advocates who argue it fails to deter repeat offenders and leads to a lack of accountability in the public sector.

Focus on Procedural Failures: Across the EU, DPAs frequently take enforcement action based on clear procedural breaches. These include failing to respond to requests within the one-month timeline, having inadequate security measures, or creating unnecessarily difficult processes for individuals to exercise their rights. This indicates that getting the operational basics right is a primary focus of regulatory oversight.

The "Missing" Article 21 Enforcement: A Freedom of Information request to the ICO revealed that, as of early 2024, it had not taken any specific enforcement actions for breaches of Article 21 itself. This absence of evidence, however, is not evidence of an absence of risk. Breaches of the Right to Object are often symptoms of broader failures. A failure to handle an objection correctly is almost always a breach of the core data protection principles in Article 5 (lawfulness, fairness, transparency), which is the most-cited article in ICO enforcement actions. Therefore, the compliance risk associated with Article 21 is not low; it is simply categorized and prosecuted under different, broader legal provisions.

Fragmented Enforcement Landscape: The GDPR's promise of a harmonized regime is challenged by the reality of fragmented enforcement. Different DPAs have different priorities, resources, and appetites for issuing large fines. The cooperation mechanism designed to handle cross-border cases has been criticized as slow and procedurally complex. This creates an unpredictable risk landscape for multinational companies, where a data processing activity deemed low-risk in one member state could attract significant regulatory attention in another. This implies that a "one-size-fits-all" GDPR compliance strategy is inherently flawed; risk assessments must be tailored to the specific jurisdictions where a company operates.

Proactive Compliance and Strategic Recommendations

Navigating the complexities of the Right to Object requires more than reactive legal analysis; it demands a proactive and embedded compliance culture. For businesses, treating data subject rights as a core operational function rather than a peripheral legal burden is the most effective strategy for minimizing risk and building customer trust.

Building a Robust Compliance Framework: Policies, Training, and Documentation

Compliance with Article 21 cannot be achieved by the legal department in isolation. It is an organizational challenge that requires a cross-functional framework involving IT, Marketing, HR, and customer service.

Policies: Businesses must develop, implement, and maintain clear internal policies for handling all data subject rights requests. The policy for Article 21 objections should include a detailed, step-by-step workflow, from initial recognition to final response and action, mirroring the checklist provided in Section 4.

Training: Regular, role-based training is essential. Marketing teams must understand the absolute nature of the right to object to direct marketing. Customer service staff must be able to identify a request, even when made informally, and know the correct escalation path. IT teams must understand the technical requirements for suppression and restriction.

Documentation: The GDPR's accountability principle requires controllers to be able to demonstrate compliance. This means meticulously documenting all Legitimate Interests Assessments (LIAs), the handling of each objection request, all communications with data subjects, and the final decisions made, including the justification for any refusal.

The Role of the Legitimate Interests Assessment (LIA)

The LIA is the foundational document for any processing based on legitimate interests and is the first line of defense against an objection. Businesses often view the LIA as a bureaucratic hurdle, but this perspective is flawed. A well-conducted and documented LIA is a critical business enablement tool. It forces the organization to clearly articulate the purpose and necessity of a processing activity

before it begins. When an objection is later received, this documented assessment becomes the primary evidence for defending the processing. Without it, the business is legally exposed and its arguments will lack credibility. The LIA should not be a one-time event but a living document, subject to review and update, especially when an objection highlights a previously unconsidered impact on an individual.

The LIA process involves a three-part test as defined by regulators like the ICO :

Purpose Test: Is there a clear, specific, and legitimate interest?

Necessity Test: Is this processing necessary to achieve that interest, or is there a less intrusive way?

Balancing Test: Are the controller's interests overridden by the individual's interests, rights, and freedoms?

Best Practices for Transparency in Privacy Notices

Compliance with the notification duty in Article 21(4) is a key element of transparency. Privacy notices must:

Explicitly State the Right: Clearly and separately inform individuals of their right to object to processing based on legitimate interests or for direct marketing purposes. This should not be buried in dense legal text.

Identify Legitimate Interests: When relying on legitimate interests as a lawful basis, the privacy notice must specify what those interests are. For example, instead of vaguely stating "for business purposes," a notice should specify "to prevent fraud," "to secure our network," or "to analyze product usage to improve our services."

Use Clear and Accessible Language: Notices should be written in plain, jargon-free language. Using a layered approach, where a short summary links to more detailed information, can improve accessibility and understanding.

Concluding Recommendations for Minimizing Risk and Fostering Trust

The Right to Object is a potent tool for data subjects and a significant compliance responsibility for businesses. To navigate this landscape effectively, organizations should adopt a strategy rooted in proactive compliance and ethical data stewardship.

Embrace Privacy by Design: The consideration of data subject rights, including the Right to Object, should be integrated into the design phase of any new product, service, or processing activity. This "privacy by design" approach ensures that potential conflicts are identified and mitigated early, rather than addressed as costly afterthoughts.

Treat the LIA as a Strategic Asset: Reframe the Legitimate Interests Assessment from a compliance hurdle to a vital risk management tool. A robust LIA is the license to process data under legitimate interests and the shield to defend that processing against challenges.

Prioritize Procedural Excellence: Recognize that many enforcement actions stem from procedural failures. Invest in the systems, policies, and training necessary to handle data subject requests efficiently, transparently, and within the mandated timelines.

Foster an Organizational Culture of Data Protection: Compliance cannot be the sole responsibility of a DPO or legal team. It requires a coordinated, cross-functional commitment to respecting data protection principles in all business operations.

Ultimately, the framework of the Right to Object is not merely a set of rules to be followed but an opportunity for businesses to build deeper, more sustainable relationships with their customers. By respecting individual autonomy, providing genuine control, and operating with transparency, businesses can transform a legal obligation into a source of competitive advantage, fostering the trust that is the cornerstone of the modern digital economy.

FAQ

What is the GDPR's Right to Object and how does it empower individuals?

The Right to Object, enshrined in Article 21 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), is a fundamental right that gives individuals significant control over their personal data. It allows a data subject to challenge and, in certain circumstances, stop the processing of their personal data. This right is particularly important when a business (data controller) is processing data based on its 'legitimate interests' or for 'public interest' tasks, rather than with the individual's explicit consent. It shifts the power dynamic, enabling individuals to assert their autonomy and potentially halt data processing based on their unique, "particular situation". Businesses are held accountable for their data processing activities under this right.

When can an individual object to data processing, and what are the key distinctions in this right?

The applicability of the Right to Object depends on the lawful basis a controller uses for processing data. It is specifically triggered when processing is based on:

Article 6(1)(e): Public Interest or Official Authority: Processing necessary for a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority.

Article 6(1)(f): Legitimate Interests: Processing necessary for the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or a third party, unless overridden by the data subject's interests or fundamental rights and freedoms.

The right has two distinct forms:

Absolute Right (Article 21(2) & 21(3)): This applies unconditionally when personal data is processed for direct marketing purposes, including any related profiling. The data subject does not need to provide a reason, and the controller must cease processing for these purposes immediately upon receiving an objection.

Qualified Right (Article 21(1)): This applies when processing is based on legitimate interests or public interest/official authority. The data subject must provide specific grounds "relating to his or her particular situation" to justify their objection. The controller can only refuse the objection if they can demonstrate "compelling legitimate grounds" for the processing that override the individual's rights, or if the processing is necessary for the "establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims".

The Right to Object does not apply when processing is based on consent (where the right to withdraw consent applies instead), performance of a contract, legal obligation, or protection of vital interests.

What is a "particular situation" and how does it impact a qualified objection?

For a qualified objection under Article 21(1), the data subject must provide specific grounds relating to their "particular situation". This means they need to articulate why the specific data processing has an unwarranted or negative impact on them. The objection carries more weight if the individual can demonstrate that the processing is causing them "substantial damage or distress", such as financial loss or reputational harm.

While the onus is on the individual to explain their grounds, best practice for businesses is to facilitate this dialogue. If an objection is vague, the controller should consider asking clarifying questions to understand the individual's concerns, aligning with GDPR's principle of facilitating data subject rights.

How does a data controller assess "compelling legitimate grounds" to refuse a qualified objection?

When a qualified objection is received, the data controller faces a critical decision. They must cease processing unless they can demonstrate "compelling legitimate grounds" that override the individual's rights and freedoms. This involves a balancing test, where the controller re-evaluates their initial Legitimate Interests Assessment (LIA) in light of the specific harm or negative impact articulated by the data subject.

The burden of proof lies entirely with the controller. Regulatory guidance from bodies like the ICO and EDPB indicates a high threshold for "compelling". For example, the EDPB suggests that "compelling" interests must be "essential" to the controller, possibly even demonstrating that continuing the processing is necessary to protect the controller from "serious immediate harm or from a severe penalty which would seriously affect its business". Examples where compelling grounds might exist include processing for critical public health research or mandatory anti-fraud measures based on legal compliance.

What are a controller's notification duties regarding the Right to Object?

Article 21(4) imposes a proactive notification duty on data controllers. The Right to Object must be "explicitly brought to the attention of the data subject and shall be presented clearly and separately from any other information" at the latest by the time of the first communication. This means it cannot be buried in a lengthy, dense privacy policy. A compliant approach involves a distinct, clearly signposted section or statement about this right, for example, in a welcome email. Failure to adhere to this clear and separate notification requirement is a common compliance pitfall and can signal a disregard for data subject rights, potentially inviting regulatory scrutiny.

What are the operational steps a business must take to handle an objection request?

Effective compliance requires robust operational readiness and a structured process for handling objections. Key steps include:

Intake & Validation: Log the request (date, method, deadline), acknowledge receipt promptly, verify that the right applies (i.e., processing based on Article 6(1)(e) or (f)), and only verify identity if there are "reasonable doubts" (avoiding disproportionate requests).

Assessment: Determine if it's an absolute right (direct marketing) or a qualified right. If qualified, carefully review the data subject's specific grounds.

Balancing Test (for Qualified Objections): Re-evaluate the existing Legitimate Interests Assessment (LIA) considering the individual's objection, weigh the controller's interests against the specific impact on the individual, and meticulously document the assessment and conclusion regarding "compelling legitimate grounds" or the legal claims exemption.

Decision & Action: Make a final decision to uphold or refuse. If upholding, cease the specific processing and/or add the data to a suppression list. If refusing, draft a clear explanation of the compelling grounds.

Communication: Respond to the data subject within one calendar month (extendable by two months for complex requests, with prior notification). Clearly state the decision, the reasons, and inform them of their right to complain to a DPA and seek a judicial remedy if the request is refused.

Requests that are "manifestly unfounded or excessive" can be refused or charged a reasonable fee, but the burden of proof for this lies entirely with the controller.

How does the Right to Object interact with other GDPR rights, like erasure and restriction?

The Right to Object is part of an interconnected ecosystem of GDPR rights:

Right to Erasure (Article 17): If a data subject's qualified objection under Article 21 is successful and there are no overriding legitimate grounds, this success becomes a valid legal ground for them to demand erasure of their personal data.

Right to Restriction of Processing (Article 18): A data subject can submit a qualified objection and simultaneously exercise their Right to Restriction on the grounds that an objection is pending verification. This creates a "pause" or "freeze" on processing the contested data while the controller conducts its balancing test, preventing further use of the data during deliberation.

Controllers must be prepared to handle these combined requests and have systems in place to "quarantine" or "flag" data when processing is restricted.

What are the real-world enforcement trends regarding Article 21 violations?

While direct enforcement actions specifically citing Article 21 may not always be highly publicised, breaches of this right often manifest as violations of broader data protection principles (e.g., lawfulness, fairness, transparency under Article 5). Key enforcement trends include:

Significant Fines: Cases like TIM S.P.A. (€27.8 million fine in Italy) demonstrate severe financial penalties for systematically ignoring direct marketing objections.

Focus on Procedural Failures: Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) frequently take action based on clear procedural breaches, such as failing to respond within timelines, requiring disproportionate identity verification (e.g., Airbnb case), or creating difficult request processes.

Link to Unlawful Marketing: In the UK, many fines related to unwanted marketing are issued under the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR), which, while separate from GDPR, address the spirit of Article 21 concerning individuals' choices about being marketed to.

Burden of Proof: Cases like the Irish DPA's search engine delisting ruling highlight that controllers must actively investigate and verify their grounds for refusing an objection, not merely assert them.

Importance of LIAs: A well-conducted and documented Legitimate Interests Assessment is crucial. Without it, a controller's ability to legally refuse a qualified objection later is severely hampered.

The enforcement landscape can be fragmented across the EU, meaning multinational companies must tailor their risk assessments to specific jurisdictions. Proactive compliance, including robust policies, training, documentation, and integrating "privacy by design," is essential to minimise risk and build trust.