The Right to Privacy in Social Media

Social media has become an integral part of our daily lives, transforming the way we connect, communicate, and share information.

The discourse surrounding privacy in the 21st century is fundamentally a discourse about power in the digital age. The rise of social media has not merely introduced new challenges to an old concept; it has re-engineered the very fabric of social interaction, blurring the lines between public and private life and transforming personal information into the primary commodity of a new economic order. Understanding the right to privacy in this context requires a multi-layered analysis that begins with its philosophical and legal foundations. The contemporary crisis of privacy is the result of a profound conceptual shift, moving from a right to physical seclusion to a far more complex and contested right of informational self-determination. This modern right is systematically challenged by the architectural design and economic imperatives of social media platforms, forcing a re-evaluation of what privacy means and how it can be protected.

1.1 The Philosophical Bedrock: From the "Right to Be Let Alone" to Informational Self-Determination

The concept of privacy, though seemingly modern in its current articulation, has deep roots in Western philosophical traditions that distinguish between the public and private spheres of life. In Ancient Greece, a clear line was drawn between the polis, the public sphere of politics and action reserved for free men, and the oikos, the private household sphere of necessity, inhabited by women and slaves. To live a life entirely in private was, in this classical view, to be deprived of one's full humanity, as true freedom and identity were forged through public perception and involvement. This classical model, however, provides a crucial starting point for understanding privacy as a spatial concept—a realm separate from the public gaze.

The modern legal conception of privacy in the United States was famously born from a reaction to technological disruption. In their seminal 1890 Harvard Law Review article, Samuel D. Warren and Louis Brandeis articulated a “right to privacy,” which they defined as “the right to be let alone”. Their argument was a direct response to the perceived threat of new technologies—specifically, "instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise"—which they argued had "invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life". This formulation framed privacy primarily as a defensive right, a shield to protect the individual's home and personal life from the unwanted intrusion of the public, akin to putting up curtains to keep out nosy neighbors or a fence to protect one's private sphere. This right was seen as stemming from the inherent dignity and individuality of a human being.

As technology evolved from the camera to the computer, this spatial and defensive concept of privacy proved insufficient. The proliferation of automated data systems in the mid-20th century necessitated a conceptual evolution. The critical shift came with the work of legal scholar Alan Westin, who, in his 1967 book Privacy and Freedom, redefined privacy not as mere seclusion but as a matter of control. Westin defined privacy as “the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others”. This was a monumental reframing. Privacy was no longer just a negative right—freedom from intrusion—but a positive, agentic right: the right to control the flow of one's personal information. This concept of informational self-determination became the cornerstone of modern data protection law and is further broken down into dimensions such as physical privacy (control over one's body and space), decisional privacy (control over personal choices), and informational privacy (control over personal data).

This legal evolution is anchored in profound philosophical principles concerning human autonomy and dignity. The right to privacy is not merely about data; it is the "essential space for individual thought, dissenting voices, and the uninhibited exploration of ideas". It creates a sphere where an individual can exist without the fear of being “molested” by others, as the philosopher John Stuart Mill argued. This private space is a prerequisite for authentic self-creation and the development of a coherent identity, free from the manipulative pressures of constant surveillance and algorithmic shaping. The erosion of this space threatens our capacity for independent, responsible decision-making. Recognizing its fundamental importance, the global community codified privacy as a universal human right. Article 12 of the 1948 U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights explicitly states, “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks”. This declaration elevated privacy from a legal concept to an inalienable human right, a status that is now being tested daily in the digital realm.

1.2 A Historical Trajectory of Privacy Law: Key Milestones and the Adaptation to Technology

The legal framework for privacy in the United States has evolved through judicial interpretation, legislative action, and reaction to technological change, creating a patchwork of protections that contrasts sharply with the comprehensive approach later adopted in Europe. While the U.S. Constitution does not contain an explicit right to privacy, the Supreme Court has found such a right to exist within the "penumbra" of several amendments. The First Amendment's protection of association and belief, the Third Amendment's prohibition against quartering soldiers in private homes, the Fourth Amendment's right to be "secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects," and the Fifth Amendment's privilege against self-incrimination have all been interpreted as creating zones of privacy.

This interpretive journey was marked by landmark cases. In his famous dissent in Olmstead v. United States (1928), a case concerning warrantless wiretaps, Justice Louis Brandeis argued that the Founders had "conferred, as against the government, the right to be let alone—the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men". His vision eventually became law. The Supreme Court formally recognized a constitutional right to privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), striking down a state law that banned the use of contraceptives by married couples, grounding the decision in a right to "marital privacy" found in the penumbras of the Bill of Rights. This was followed by

Katz v. United States (1967), which extended Fourth Amendment protections to any place where a person has a "reasonable expectation of privacy," a crucial standard in the age of electronic surveillance.

As mainframe computers and automated databases became more common, Congress began to act. The Privacy Act of 1974 was a significant milestone, establishing a Code of Fair Information Practice for federal agencies regarding their collection and use of personally identifiable information. A decade later, the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986 was passed, representing one of the first major attempts to protect "data privacy" by regulating the interception of electronic communications while in transit and in storage. Concurrently, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) emerged as the nation's primary federal agency for privacy enforcement in the commercial sector, using its authority to police "unfair or deceptive" practices. The legal scholar William Prosser also contributed to the development of private remedies by outlining four influential privacy torts, including "intrusion upon seclusion" and "public disclosure of embarrassing private facts," which are still used today.

However, this trajectory of expanding privacy rights was sharply curtailed in the early 21st century. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the U.S. government passed the USA PATRIOT Act, which dramatically expanded the state's surveillance powers, allowing for greater monitoring of phone and email communications in the name of national security. This move prioritized collective security over individual privacy, representing a significant rollback of previously established protections.

This American focus on limiting government intrusion and providing consumer remedies contrasts with the European approach, which has long treated privacy as a fundamental human right applicable to both state and private actors. As early as 1981, the Council of Europe adopted the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data. This was followed by the landmark EU Data Protection Directive of 1995, which harmonized privacy laws across the European Union and established a comprehensive, rights-based framework. This directive set the stage for a global regulatory divergence, with Europe championing a robust, universal right to data protection while the U.S. pursued a more sectoral and reactive approach. This fundamental difference in legal philosophy continues to shape the global privacy landscape today.

1.3 The Public and Private Realms in the Era of Social Media: Redefining Boundaries

Social media platforms have fundamentally re-architected the relationship between the public and private spheres, creating a novel environment that defies traditional categorization. Historically, the distinction was clearer: the home was a private sphere, the town square a public one. Social media, however, represents a hybrid space—a quasi-public forum where private life is performed for a curated audience. Intimate thoughts, personal relationships, daily routines, and precise locations, once confined to the private realm, are now routinely broadcast, shared, and commodified. This is not an accidental byproduct of the technology but its core design principle. The business model of platforms like Meta and TikTok is predicated on maximizing user engagement and disclosure, as the data generated from these activities is the raw material for their advertising engines.

This engineered environment gives rise to the "privacy paradox," the widely observed phenomenon where users express strong concerns for their privacy yet continue to engage in extensive online sharing. This paradox is often misconstrued as individual hypocrisy or carelessness. A more accurate analysis reveals it to be a systemic outcome of platform design and power asymmetry. Users are confronted with a stark choice: participate in modern social and professional life by accepting invasive terms, or opt out and risk social and economic isolation. The "consent" given is often illusory, embedded within lengthy and indecipherable terms of service that function as adhesion contracts—non-negotiable agreements that users must accept in their entirety to use the service.

Furthermore, platforms cultivate an "illusion of control" through user-facing privacy settings. Dashboards and check-up tools allow users to manage the visibility of their content, creating a sense of agency. However, these settings primarily govern who can see a user's posts, not whether the platform itself can collect, analyze, and monetize the underlying data. This creates a state of resignation among users, who recognize the need to protect their data but feel powerless to do so against vast, opaque corporate systems.

The historical evolution of privacy from a negative right (freedom from intrusion) to a positive right (the right to control information) is being subtly but powerfully inverted by this dynamic. The Warren and Brandeis model was defensive, aimed at protecting the home from the prying eyes of the press. The Westin and GDPR model is agentic, empowering the individual with control over their data flows. The social media model, however, requires a functional waiver of this right to control as a precondition for participation. Privacy is reframed not as an inalienable right but as a transactional commodity, traded for access to the digital public square. This represents a profound normative shift, driven not by public debate or philosophical consensus, but by the unchallenged logic of a corporate business model. The very meaning of privacy is being re-engineered in the public consciousness, from a fundamental right to a configurable, and ultimately surrenderable, preference.

Part II: The Regulatory Framework for Social Media Privacy: A Comparative Analysis

The global response to the privacy challenges posed by social media has been anything but uniform. A fragmented regulatory landscape has emerged, defined by a fundamental philosophical divergence between the European Union's rights-based approach and the United States' consumer-centric model. This has created a complex "geography of privacy," where the rights of a user can change dramatically depending on their physical location. For global social media platforms, this fragmentation poses significant compliance challenges, forcing them to navigate a patchwork of conflicting legal obligations. For users, it means that the protection of their personal data is not a universal guarantee but a variable dependent on national sovereignty.

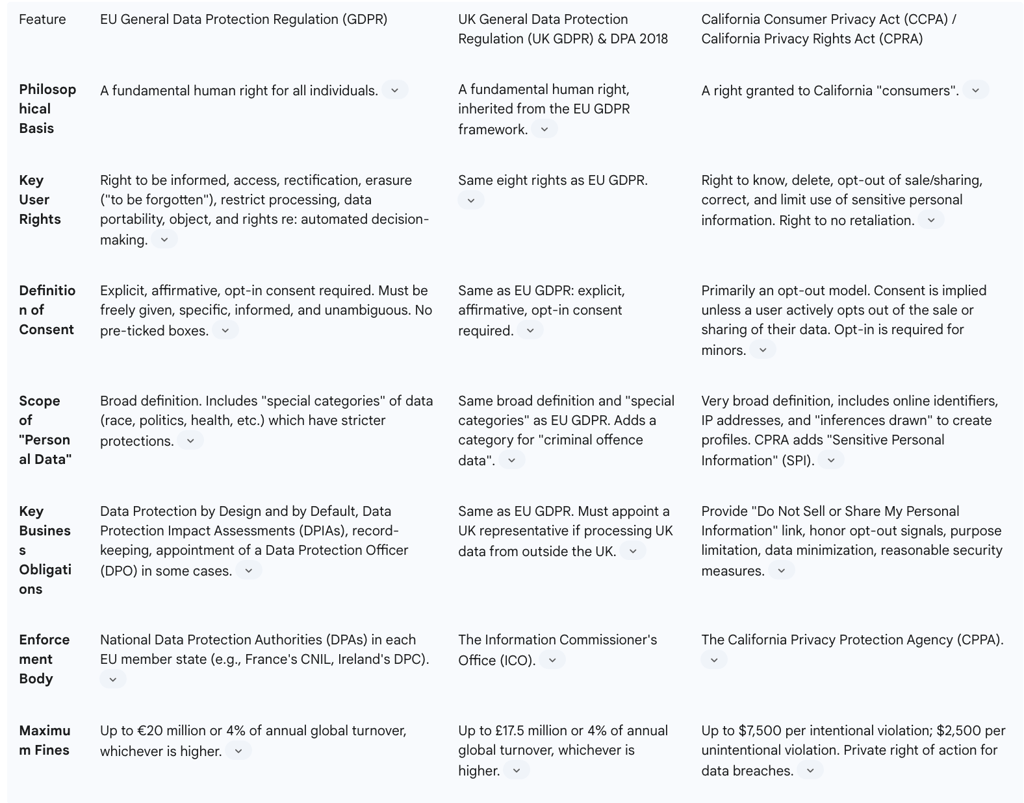

2.1 The European Standard: The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the UK's DPA 2018

The European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force in May 2018, is widely considered the global gold standard for data protection. It is a comprehensive and stringent law built on the philosophical foundation that privacy is a fundamental human right. Its influence is global, as it applies not only to organizations based in the EU but to any entity worldwide that processes the personal data of EU residents.

The GDPR is structured around a set of core principles that govern all data processing activities. These principles mandate that personal data must be:

Processed lawfully, fairly, and in a transparent manner: Organizations must have a valid legal basis for processing data and must be open about their practices.

Collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes: Data collected for one purpose cannot be used for another incompatible purpose without further consent.

Adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary (data minimization): Organizations should only collect the data they absolutely need.

Accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date: Inaccurate data must be rectified or erased.

Kept in a form which permits identification for no longer than is necessary (storage limitation): Data should be deleted once it is no longer needed.

Processed with appropriate security (integrity and confidentiality): Organizations must protect data from unauthorized access, loss, or destruction.

Accountability: The data controller is responsible for and must be able to demonstrate compliance with all of these principles.

A cornerstone of the GDPR is the empowerment of individuals through a robust set of user rights. These eight fundamental rights give data subjects significant control over their personal information. They include: the right to be informed about data collection; the right of access to one's data; the right to rectification of inaccurate data; the right to erasure, famously known as the "right to be forgotten"; the right to restrict processing; the right to data portability, allowing users to move their data between services; the right to object to certain types of processing (like direct marketing); and rights in relation to automated decision-making and profiling, which protect individuals from decisions made solely by algorithms without human involvement. The regulation's definition of consent is particularly strict, requiring a "freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous" indication of wishes, typically through a clear affirmative action. This effectively bans practices like pre-ticked opt-in boxes and bundled consent.

Following its departure from the European Union, the United Kingdom implemented its own data protection regime through the Data Protection Act (DPA) 2018 and the subsequent adoption of the "UK GDPR". The DPA 2018 was enacted to align UK law with the EU GDPR before Brexit, and the UK GDPR essentially incorporated the full text of the EU regulation into domestic law after the transition period ended. The UK government also secured an "adequacy decision" from the EU, confirming that its data protection standards are equivalent, which allows for the continued free flow of data between the UK and the EU.

While the UK GDPR is largely identical to its EU counterpart, maintaining the same core principles and user rights, there are some notable divergences. The UK has set the age of consent for data processing at 13, lower than the GDPR's default of 16. The DPA 2018 also provides for more flexible rules regarding the processing of criminal conviction data and is more permissive in allowing automated decision-making and profiling, provided there are legitimate grounds for doing so. Furthermore, the UK regime allows for certain data subject rights to be waived if they inhibit processing for scientific, historical, or statistical purposes. The maximum penalty for non-compliance under the UK GDPR is £17.5 million or 4% of an organization's annual global turnover, whichever is higher.

2.2 The American Approach: California's CCPA and CPRA as National Bellwethers

In contrast to Europe's rights-based framework, the United States has traditionally taken a sectoral approach to privacy law, with specific rules for areas like healthcare (HIPAA) and finance (GLBA). The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which took effect in 2020, marked a significant shift by creating the first comprehensive, economy-wide privacy law in the U.S.. However, its philosophical framing is distinct from the GDPR: it grants rights to "consumers" rather than to all individuals as a fundamental right.

The CCPA provides California residents with several core rights, including:

The right to know: Consumers can request that a business disclose the categories and specific pieces of personal information it has collected about them, the sources of that information, the purpose for collecting it, and the categories of third parties with whom it is shared.

The right to delete: Consumers can request the deletion of their personal information held by a business, subject to certain exceptions.

The right to opt-out: Consumers have the right to direct a business not to "sell" their personal information to third parties.

A key strength of the CCPA is its remarkably broad definition of "personal information." It includes not only obvious identifiers like names and addresses but also a wide range of digital data such as IP addresses, cookies, device identifiers, browsing history, geolocation data, and, critically, "inferences drawn" from any of this information to create a profile reflecting a consumer's "preferences, characteristics, psychological trends, predispositions, behavior, attitudes, intelligence, abilities, and aptitudes". This expansive definition directly targets the profiling practices at the heart of the social media business model.

Recognizing some of the CCPA's limitations and loopholes, California voters approved Proposition 24, the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), in November 2020. Often called "CCPA 2.0," the CPRA significantly amended and expanded the CCPA, with most of its provisions becoming operative on January 1, 2023. The CPRA introduced several crucial enhancements. It created a new category of "Sensitive Personal Information" (SPI), which includes government IDs, precise geolocation, racial or ethnic origin, union membership, religious beliefs, and the contents of a consumer's private communications like mail, email, and text messages.

The CPRA established two new consumer rights: the right to correct inaccurate personal information and the right to limit the use and disclosure of their SPI. Perhaps most importantly, it closed a major loophole by expanding the "right to opt-out of sale" to the "right to opt-out of sale or sharing." The term "sharing" was explicitly defined as disclosing personal information to a third party for "cross-context behavioral advertising," whether or not for monetary consideration. This definition was a direct legislative assault on the ad-tech ecosystem's core practice of tracking users across different websites and apps to serve targeted ads—a practice that companies like Facebook had argued did not constitute a "sale" of data under the original CCPA. Finally, the CPRA established the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA), a new, dedicated body with the power to implement and enforce the law, giving it significantly more teeth than the previous enforcement regime under the state's Attorney General.

The evolution from CCPA to CPRA demonstrates a crucial development in privacy regulation. While the GDPR establishes broad, principles-based restrictions, the CPRA shows regulators becoming more technologically sophisticated and surgically precise. They are moving beyond setting general principles to directly targeting the specific mechanisms of surveillance capitalism. The CPRA's explicit definition of "sharing" to include cross-context behavioral advertising was not just a minor tweak; it was a direct attack on the primary revenue engine of the modern internet. This signals a new and more confrontational phase of privacy regulation, where lawmakers are no longer just giving users rights but are actively seeking to regulate, and potentially dismantle, the business models that they see as inherently harmful.

2.3 Global Fragmentation and Convergence: International Standards and Cross-Border Data Flows

The GDPR and the CCPA/CPRA represent the two most influential models for privacy regulation, but they are part of a much broader global conversation. Other international bodies and nations have also developed their own frameworks, contributing to a complex and often fragmented global landscape. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) issued its influential Privacy Guidelines as early as 1980, establishing foundational principles that have shaped many subsequent laws. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum established a voluntary Privacy Framework in 2004 and a Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) System in 2011 to facilitate secure data transfers among its 21 member economies. Canada's Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) is another example of a comprehensive national privacy law.

This proliferation of different legal standards creates significant challenges for the cross-border transfer of data, which is the lifeblood of global social media platforms. The GDPR, for instance, restricts the transfer of personal data outside the European Economic Area (EEA) unless the destination country has been deemed by the European Commission to provide an "adequate" level of data protection. This has led to a system of "adequacy decisions," where the EU formally recognizes a country's legal framework as equivalent to its own, allowing data to flow freely.

The friction created by these differing standards is not merely theoretical. It has led to major legal and business confrontations. For years, data transfers between the EU and the U.S. were governed by frameworks like the Safe Harbor and its successor, the Privacy Shield, both of which were invalidated by the European Court of Justice over concerns that U.S. surveillance laws did not adequately protect the rights of EU citizens. This legal uncertainty has created immense compliance burdens for companies. In 2022, Meta went so far as to state in a regulatory filing that if a new transatlantic data transfer framework was not adopted, it might be forced to shut down services like Facebook and Instagram in Europe, a clear illustration of the high stakes involved in this regulatory friction. While a new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework has since been established, the underlying tension between Europe's fundamental rights approach and U.S. national security and commercial surveillance practices remains a persistent source of instability in the global data ecosystem.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Global Privacy Regulations

Part III: Corporate Governance of Data: Platform Policies in Practice

While legislative frameworks like the GDPR and CPRA set the legal boundaries for data privacy, the day-to-day governance of user information is executed through the privacy policies and terms of service of social media platforms themselves. A critical examination of these corporate documents reveals that they are not merely informational disclosures but powerful instruments of governance. They are meticulously crafted to secure the broadest possible rights for the platform to collect, analyze, and monetize user data, while creating a "legal fiction" of informed consent. Through strategic use of complexity, ambiguity, and the illusion of user control, these policies legitimize a business model that is fundamentally predicated on pervasive surveillance.

3.1 The Architects of Our Digital Lives: Examining the Privacy Policies of Meta, X, TikTok, and LinkedIn

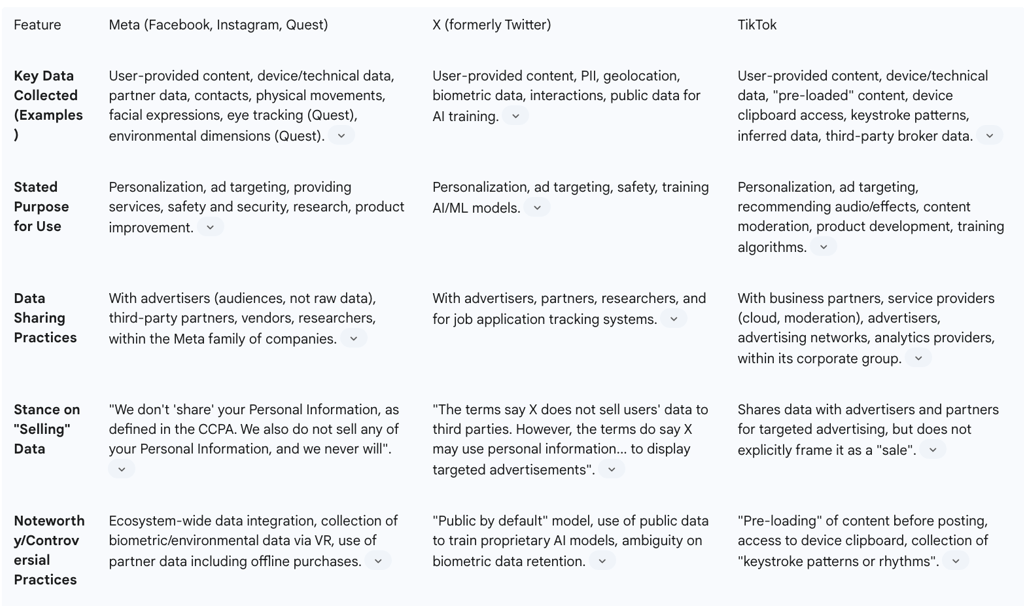

A deep dive into the privacy policies of the world's largest social media platforms exposes a shared architecture of extensive data collection, though each platform has its own unique and often alarming nuances.

Meta (Facebook, Instagram, and VR Products): Meta's privacy policy exemplifies an ecosystem-wide approach to data harvesting. Information is collected not just from what users actively provide—posts, messages, and profile information—but from a vast web of passive and inferred sources. This includes data from the devices users access their services on (computers, phones, connected TVs), information from third-party partners and advertisers (including offline purchase data), and even data provided by other users, such as when a user's contacts are uploaded or they are tagged in a photo. This creates a comprehensive profile that extends far beyond a user's direct interactions with the platform.

The expansion into virtual reality with Meta Quest products has opened a new, even more intimate frontier of data collection. Meta's policies for these devices detail the collection of biometric and environmental data, including the position and orientation of the headset for body tracking, abstracted gaze data from eye tracking, data on natural facial expressions, and even the physical dimensions of the user's room. This data is used not only to power the VR experience but also for the same purposes as other Meta data: measurement, analytics, and serving ads. In its policies, Meta is careful to state that it does not "sell" personal information, a crucial legal distinction designed to navigate laws like the CCPA. However, it openly acknowledges sharing data with a wide array of partners for "business purposes," a practice that achieves similar outcomes for the ad-tech industry.

X (formerly Twitter): The privacy policy of X is characterized by its "public by default" philosophy, where all information submitted is presumed to be public unless a user actively changes their settings. The platform collects a broad spectrum of data, including personally identifiable information (PII), geolocation, interactions, and even biometric data, which it uses for targeted advertising. A significant and recent evolution in X's policy is the explicit right to use publicly available information to "help train our machine learning or artificial intelligence models". This clause represents a major shift in data repurposing, transforming user content from mere communication into raw material for developing new, proprietary AI systems—a purpose far removed from what users likely envisioned when they signed up. The policy is also notably vague on how long it retains sensitive information like biometric data, creating significant uncertainty and concern.

TikTok: TikTok's data collection practices are arguably the most aggressive among the major platforms. Its policy details the collection of user-generated content before it is even posted, a practice known as "pre-loading," which is used to recommend audio and other features. The app also seeks permission to access a user's device clipboard, allowing it to see content that has been copied, even if it is never pasted into the app. The technical information collected is exceptionally granular, including not just IP address and device type but also "keystroke patterns or rhythms," providing a unique behavioral fingerprint of the user. Like its competitors, TikTok infers characteristics such as age, gender, and interests and supplements its own data with information from a vast network of third-party data brokers and advertising partners.

LinkedIn: As a professional networking platform, LinkedIn frames its data collection as being in service of career development. Its policy details the collection of standard contact and technical data (IP address, browser type) to personalize the user experience and for marketing purposes. However, despite its professional veneer, its practices raise similar privacy concerns. Users and analysts have noted that its privacy settings can be particularly confusing and difficult to navigate, making it challenging for individuals to effectively prevent their data from being shared with marketers and advertisers. The platform also allows for the collection of data to conduct market research and analyze site usage to improve its services.

3.2 Consent, Collection, and Commodification: A Critical Assessment of Terms of Service

The concept of "consent" is central to the legitimacy of data collection under most privacy laws, particularly the GDPR, which requires it to be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous. However, the model of consent employed by social media platforms is a legal and practical fiction. Consent is not sought for specific data processing activities; rather, it is bundled into a monolithic, non-negotiable Terms of Service agreement that users must accept in its entirety to access the platform. This take-it-or-leave-it approach, characteristic of an adhesion contract, removes any element of free choice.

Furthermore, the sheer volume and complexity of the data collected—ranging from direct inputs to inferred psychological traits and keystroke rhythms—make the possibility of "informed" consent a practical impossibility for any user who is not a dedicated data privacy expert. This structure ensures that platforms can claim legal cover for their practices while engaging in a form of data extraction that is far beyond the reasonable expectations of their users.

This leads to the inescapable conclusion that on "free" social media platforms, the user is not the customer but the product. A critical analysis of the privacy policies reveals that the primary purpose of this vast data collection apparatus is not merely to "provide and improve the service" but to construct intricate, dynamic user profiles. These profiles are then used to power the platforms' core revenue stream: selling targeted advertising space to third parties. The user's attention, shaped and directed by data-driven algorithms, is the ultimate commodity being sold.

3.3 Transparency in Practice: The Gap Between Policy and User Understanding

While privacy policies are often lengthy and seemingly comprehensive, they frequently achieve opacity by design. The language used is often legalistic, broad, and ambiguous. For example, policies that state data may be shared with unnamed "partners" for vague purposes such as "research and product improvement" or "business purposes" provide no meaningful transparency to the user. This lack of specificity makes it nearly impossible for an individual to know the full extent of who has access to their data and for what precise reasons, undermining the very principle of transparency.

To counter accusations of opacity, platforms have developed user-facing tools like "Privacy Checkups" and data dashboards. These tools provide an interface for users to manage certain aspects of their privacy, such as who can see their posts, who can tag them, or what ad topics they are interested in. While these features are a step toward user agency, they primarily create an "illusion of control". They allow users to adjust surface-level settings related to content

visibility and ad personalization, which can placate privacy concerns. However, they typically do little to stop the fundamental, underlying data collection and profiling that powers the platform's business model. A user can choose to hide their posts from the public, but they cannot easily prevent the platform from analyzing the content of those posts for its own purposes. The default settings on these platforms are invariably calibrated for maximum data collection and public visibility, requiring users to be proactive and sophisticated to claw back even a modicum of privacy. This design choice ensures that while the platform appears to offer control, the vast majority of users remain in the default, data-rich environment that is most profitable for the company.

The recent move by platforms like X to include clauses allowing the use of public data to train proprietary AI models marks a significant and alarming escalation in this dynamic of data repurposing. This development represents a fundamental shift in the implicit contract between user and platform. Initially, the rationale for data collection, however flawed, was tied to the immediate service provided: personalizing the feed and targeting ads. The user's data was used to shape their experience on the platform. The new AI training clauses retroactively and prospectively change this deal. A user's public posts, photos, and expressions are no longer just content for communication; they are now raw, unlabeled training data for a completely separate and vastly more powerful commercial technology. This repurposing is far beyond what any user could have reasonably foreseen or consented to when they joined the platform. It raises profound new questions about intellectual property and labor, as millions of users are now unwitting, unpaid contributors to the construction of massive commercial AI systems that may one day compete with technologies from Google or OpenAI. This unilateral expansion of data use, buried within an updated privacy policy, is a stark illustration of the power imbalance at the heart of the social media ecosystem and a clear signal of the next major battleground for digital privacy.

Table 2: Privacy Policy Summary of Major Social Media Platforms

Part IV: Systemic Threats to Digital Privacy

The erosion of privacy on social media is not the result of isolated incidents or technical glitches. It is a systemic issue stemming from a business model that treats personal data as a resource to be extracted and monetized. This section examines the concrete manifestations of this systemic threat, moving from the abstract principles of data collection to the real-world harms they produce. Using the Cambridge Analytica scandal as a central case study, it will be argued that such events are not anomalous "breaches" but are the inherent and predictable outcomes of a system built on the logic of surveillance capitalism.

4.1 The Business of Surveillance: Algorithmic Profiling and the Economics of Personal Data

At the heart of the social media economy lies the practice of algorithmic profiling. This is the process by which platforms use complex, automated systems to collect and analyze vast quantities of user data to construct detailed, dynamic profiles of individuals. These profiles are far more sophisticated than simple demographic summaries. They encompass not only a user's stated preferences and activities but also their inferred psychological traits, emotional states, political leanings, vulnerabilities, and predicted future behaviors.

The mechanism for this profiling is relentless and comprehensive. Platforms capture data from every conceivable interaction: every like, share, comment, search query, direct message, and video watched. They monitor how long a user's cursor hovers over a post, track their geolocation via their device, and log detailed technical information. This internally collected data is then augmented with information purchased from third-party data brokers and data collected by partners through tracking pixels and cookies embedded across the web. All of this information is fed into proprietary machine learning models that categorize, score, and segment users, creating what the scholar Shoshana Zuboff has termed "prediction products". These products, which forecast the likelihood of a user clicking an ad, buying a product, or adopting a belief, are the true assets of the platform, sold to advertisers and other third parties.

This practice raises profound privacy and ethical concerns. It moves beyond the simple violation of data protection to pose a direct threat to individual autonomy. By understanding a user's psychological triggers, these systems can be used not just to predict but to actively shape and manipulate their behavior, a power that is exercised without the user's knowledge or meaningful consent. This creates a staggering power asymmetry between the individual user and the corporate platform, which knows more about the user than the user knows about it. This asymmetry has tangible consequences, enabling discriminatory practices in areas such as dynamic pricing (charging different users different prices for the same product), credit scoring, job screening, and housing advertisements. The opaque nature of these algorithms—often referred to as "black boxes"—means that users are typically unaware of how they are being profiled and categorized, leading to a sense of powerlessness and what some researchers have termed "algorithmic disillusionment".

4.2 Landmark Failure: A Definitive Analysis of the Cambridge Analytica Scandal and its Aftermath

The Cambridge Analytica scandal, which erupted into public view in March 2018, serves as the quintessential case study of how the architecture of social media surveillance can be weaponized for political purposes. It was not a hack or a breach in the traditional sense; it was a demonstration of the system working as it was designed, with devastating consequences for user privacy and democratic integrity.

The scandal's origins lie with a University of Cambridge researcher named Aleksandr Kogan, who developed a personality quiz app called "thisisyourdigitallife". Through Facebook's Open Graph Application Programming Interface (API)—a tool designed to allow developers to build applications that integrated with the platform—the app was able to harvest vast amounts of data. Approximately 270,000 to 300,000 Facebook users were paid to take the quiz and consented to their data being collected for "academic use". However, the crucial design feature of the API at the time allowed the app to also scrape the personal data of the quiz-takers' entire friend networks, without their knowledge or consent. This cascaded the data collection to an estimated 50 to 87 million users, the vast majority of whom had never interacted with Kogan's app.

Kogan then committed a clear violation of Facebook's platform policies by transferring this massive and richly detailed dataset to Cambridge Analytica (CA), a political consulting firm that specialized in data-driven behavioral microtargeting. CA used the data to construct detailed "psychographic profiles" of millions of American voters, classifying them according to the "OCEAN" model of personality traits (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism). These profiles were then used to create and target highly personalized political advertisements for the 2016 presidential campaigns of Ted Cruz and, most famously, Donald Trump, aiming to influence voter behavior on an unprecedented scale.

Facebook's initial response to the revelations was a masterclass in semantic deflection. The company vehemently insisted that the incident was "unequivocally not a data breach," arguing that no systems were infiltrated and no passwords were stolen. This defense, while technically narrow, was profoundly misleading. It sought to frame the problem as one of external malice, like a burglar breaking into a house. The reality was that the data was harvested using Facebook's own developer tools, which were functioning precisely as they were intended to. The catastrophic failure was not one of technical security but of policy, oversight, and a fundamentally permissive approach to data access that prioritized developer growth over user privacy.

The long-term impact of the scandal was seismic. It became a watershed moment that crystallized public and regulatory anxiety about the power of social media. The fallout included a precipitous drop in public trust, a more than $100 billion loss in Facebook's market capitalization in the immediate aftermath, and significant regulatory penalties, including a landmark $5 billion fine from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and a £500,000 fine from the UK's Information Commissioner's Office. The scandal triggered government hearings around the world and acted as a powerful catalyst for the passage and enforcement of privacy regulations like the GDPR and CCPA. In response, Facebook and other platforms were forced to significantly restrict API access, pause their app review processes, and introduce more transparency tools for users and advertisers. Cambridge Analytica ultimately filed for bankruptcy, but the scandal's legacy endures as a stark warning of the dangers inherent in the surveillance-based business model.

4.3 A Pattern of Breaches: Other Major Data Scandals and Their Impact on Public Trust

The Cambridge Analytica affair, while uniquely impactful, was not an isolated incident. It is part of a persistent pattern of privacy failures across the social media industry and the broader digital ecosystem, demonstrating that the risks are systemic. A review of other major scandals underscores the pervasive nature of the threat to personal data.

Meta/Facebook has been at the center of numerous other privacy debacles. In 2021, it was revealed that the personal data of over 533 million Facebook users—including phone numbers, full names, and locations—had been scraped from the platform and posted on a hacking forum. In 2023, the company's Irish subsidiary was hit with a record-breaking €1.2 billion ($1.3 billion) fine by EU regulators for illegally transferring user data to the United States, a practice the European Data Protection Board described as "systematic, repetitive and continuous". Its subsidiary, Instagram, was also fined €405 million in 2022 for mishandling the data of children.

X (formerly Twitter) has also faced significant penalties. In 2022, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission fined the company $150 million for deceptively using users' phone numbers and email addresses for targeted advertising. The data had been collected under the pretense of securing user accounts via two-factor authentication, a clear violation of user trust and privacy expectations.

Other platforms have not been immune. LinkedIn suffered a major breach in 2012 that compromised the email addresses and passwords of 165 million users; the data was later found being sold on the dark web in 2016. The once-dominant

MySpace experienced a massive breach in 2016 that exposed the credentials of over 360 million accounts. Even Google's now-defunct social network,

Google+, was shut down in 2018 after the discovery of a software bug that had exposed the private data of up to 500,000 users to external developers.

These incidents are not confined to social media platforms alone but extend to the wider data economy with which they are deeply intertwined. The 2017 breach at the credit reporting agency Equifax, which exposed the highly sensitive personal and financial data of 147.4 million people, and the 2016 hack of Friend Finder Network, an adult entertainment company, which affected 412 million accounts, illustrate the systemic vulnerability of personal data in the digital age.

The industry's consistent framing of these events as external "breaches," "hacks," or the work of "malicious actors" is a deliberate rhetorical strategy designed to deflect corporate responsibility. This narrative conveniently casts the platform as a fellow victim alongside its users. However, a deeper analysis reveals that many of the most significant privacy harms are not the result of system failures but of the systems functioning exactly as designed. The repurposing of security phone numbers for advertising by X was not a hack; it was an internal business decision. The core practice of algorithmic profiling is not a breach; it is the fundamental, intended operation of the platform's business model. This distinction is critical. The term "data breach" is insufficient to capture the full scope of the problem. A more accurate concept is "programmatic privacy violation"—harm that is architecturally embedded and results from the platform's own business logic. This reframes the issue from one of cybersecurity (keeping bad actors out) to one of corporate governance and ethics (re-evaluating the core business model itself). For regulators, this implies that focusing solely on breach notification laws is inadequate; they must also regulate the underlying programmatic practices that make such violations inevitable.

Part V: The Technological Double-Edged Sword

Technology is at the heart of the social media privacy crisis, acting as both the engine of surveillance and a potential source of protection. Innovations in artificial intelligence, particularly facial recognition, have dramatically amplified the scale and intimacy of data collection, creating unprecedented risks to individual privacy and autonomy. At the same time, a growing field of Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) offers a powerful technical defense, promising ways to secure data and empower users. This technological duality presents a critical choice for the future of the internet. However, the path forward is not merely a technical decision; it is a business model decision. The adoption of robust privacy protections is fundamentally at odds with the economic incentives of surveillance capitalism, making this a battle for the soul of the digital economy.

5.1 The Panoptic Sort: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Facial Recognition on User Privacy

Artificial intelligence is the supercharger of the social media surveillance engine, and facial recognition technology (FRT) is one of its most potent and invasive applications. The process is technologically sophisticated but conceptually straightforward: an AI system captures a facial image from a photo or video, preprocesses it to optimize for analysis, and then extracts key biometric data—such as the distance between the eyes, the shape of the jaw, and the position of the nose. These measurements are converted into a unique numerical code, or "faceprint". This faceprint can then be compared to a single stored template for verification (1:1 matching, like unlocking a phone) or scanned against a massive database to find a match for identification (1:N matching). Social media platforms have been pioneers in this domain; Facebook's DeepFace system, for example, was developed to power its photo-tagging suggestions, training its AI on the billions of user-uploaded images on its platform.

The privacy risks associated with FRT are profound and unique. Unlike a password or a credit card number, a person's face cannot be easily changed or encrypted. A breach of facial data is therefore permanent and irreparable, creating lifelong risks of identity theft, stalking, and harassment. The technology enables mass surveillance on an unprecedented scale, often without the subject's knowledge or consent. The case of Clearview AI, a company that scraped over 30 billion images from social media and the open web to build a facial recognition database for law enforcement, is a stark example of this capability. This practice effectively turns the public internet into a perpetual, non-consensual biometric lineup.

The ethical concerns are equally severe, particularly regarding bias and discrimination. AI models are not objective; they are trained on data, and if that data reflects existing societal biases, the AI will learn, perpetuate, and even amplify them. Numerous studies have demonstrated that commercial facial recognition systems are significantly less accurate when identifying women, people of color, and younger individuals. The MIT Media Lab's "Gender Shades" project, for instance, found error rates for identifying darker-skinned women to be as high as 35%, compared to less than 1% for lighter-skinned men. This is not a minor technical flaw; it has devastating real-world consequences, leading to wrongful arrests, discriminatory targeting by law enforcement, and the reinforcement of systemic inequalities in areas like employment and housing.

The future trajectory of this technology points toward an even more deeply surveilled society. Experts predict the seamless integration of FRT with augmented and virtual reality platforms to create hyper-realistic avatars and track facial expressions in real-time. This will be combined with other biometric technologies like voice recognition and even gait analysis (identifying individuals by the way they walk) to create a multi-modal surveillance apparatus capable of real-time tracking and behavior prediction. In this future, our most personal and expressive characteristics risk becoming data points in a vast system of monitoring and control.

5.2 A Technological Defense: The Role and Potential of Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs)

In response to the growing threat of digital surveillance, a field of computer science has emerged dedicated to developing Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs). These are a class of technologies designed to embody the principles of data protection, such as data minimization and "privacy by design," directly into the architecture of systems. PETs offer a technological pathway to reconciling the demand for data-driven services with the fundamental right to privacy.

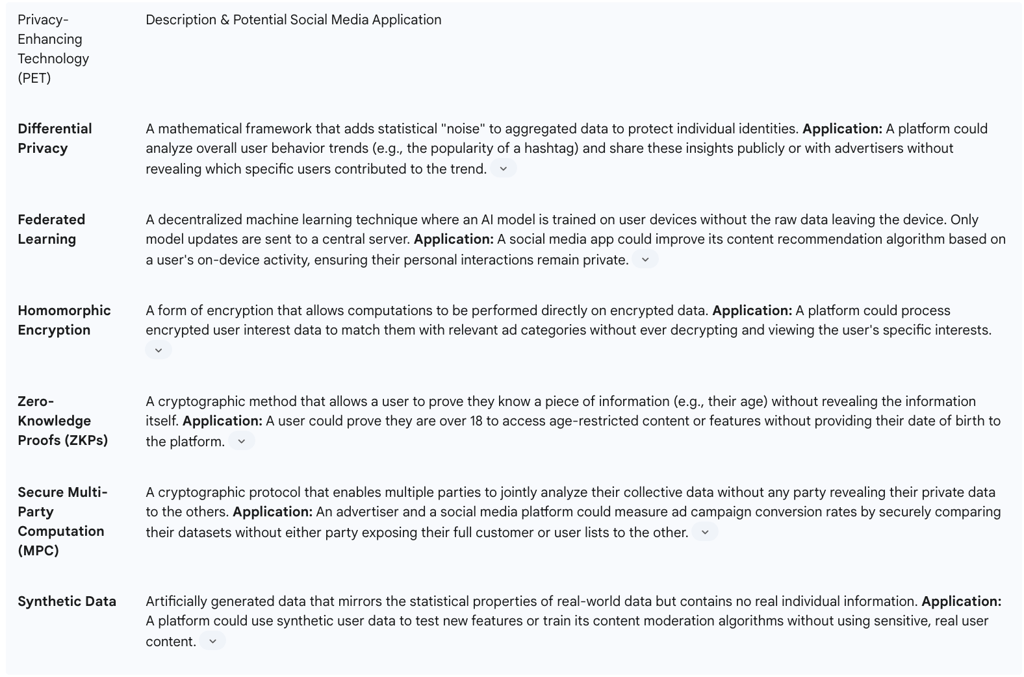

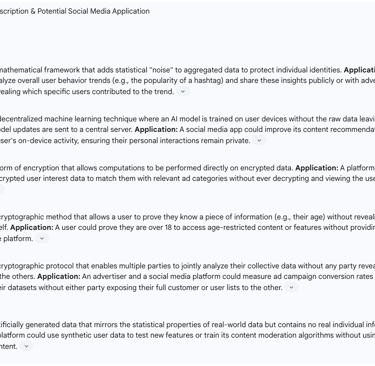

A number of key PETs have shown significant promise, each offering a different method for protecting data while enabling useful computation:

Differential Privacy: This is a mathematical technique that allows organizations to gather insights from large datasets while providing strong guarantees that no individual's information can be identified. It works by strategically adding a precisely calculated amount of statistical "noise" to the data before it is analyzed. For example, a social media platform could use differential privacy to study overall trends in user engagement or the popularity of certain topics without being able to link any specific activity to a specific user. The U.S. Census Bureau has notably adopted this technique to protect the privacy of respondents in its public data releases.

Federated Learning: This is a decentralized approach to training machine learning models. Instead of pooling all user data on a central server for analysis, the AI model is sent out to be trained directly on individual user devices (like a smartphone). The raw data never leaves the device; only the resulting improvements to the model are sent back to the central server and aggregated. A social media app could use federated learning to improve its recommendation engine or predictive text features based on a user's personal activity, all while keeping that activity data private and secure on their own device.

Homomorphic Encryption: This is a groundbreaking form of encryption that allows mathematical computations to be performed directly on encrypted data without ever decrypting it. This means a third party could process sensitive information on behalf of a user without being able to read the information itself. In a social media context, a platform could use homomorphic encryption to analyze encrypted user preferences to serve relevant advertising, without the platform itself ever having access to the user's decrypted interests.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs): This is a cryptographic method by which one party (the prover) can prove to another party (the verifier) that a given statement is true, without conveying any information apart from the fact that the statement is indeed true. A powerful application for social media would be age verification. Using a ZKP, a user could prove to a platform that they are over the age of 18 without having to reveal their actual date of birth or any other identifying information.

Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC): This technique allows multiple different parties to jointly compute a function using their combined private data, without any of the parties having to reveal their individual data to the others. For example, an advertiser and a social media platform could use MPC to measure the effectiveness of an ad campaign by securely matching their respective datasets (e.g., the platform's ad exposure data and the advertiser's sales data) without either party having to share their raw data with the other.

Synthetic Data: This involves creating artificial datasets that mimic the statistical properties and patterns of real data but contain no actual personal information. Social media companies could use high-quality synthetic data to test and refine their algorithms, develop new features, or conduct research without putting real user data at risk.

The primary obstacle to the widespread adoption of these powerful technologies by incumbent social media platforms is not their technical feasibility, but their fundamental incompatibility with the prevailing business model. The logic of surveillance capitalism is predicated on the principle that more data—and more granular data—is always better. This data is the asset that drives the hyper-targeted advertising engine. PETs, by their very nature, are designed to do the opposite: to minimize data collection, to add noise, to keep data decentralized, and to make it computationally inaccessible through encryption. Implementing these technologies in their most robust forms would directly undermine the precision and, therefore, the profitability of the existing advertising model. This creates a powerful financial disincentive for large platforms like Meta and Google to embrace them beyond what is legally mandated.

This economic conflict is creating a clear bifurcation in the market. For the large, surveillance-based incumbents, privacy is a compliance cost and a public relations challenge. For a new wave of smaller, privacy-focused challengers (such as the messaging app Signal or the social network MeWe), privacy is their core value proposition and competitive differentiator. They build their platforms from the ground up using technologies like end-to-end encryption and principles of minimal data collection to attract users who are increasingly disillusioned with the incumbents. This suggests that the future of digital privacy may be shaped as much by market competition and consumer choice as it is by top-down regulation, with PETs serving as the key technological battleground.

Table 3: Typology of Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) and Their Social Media Applications

Part VI: The User Dilemma: Navigating Control, Consent, and Content

From the user's perspective, the social media landscape is a complex and often contradictory environment. Platforms offer an array of settings and tools that promise control, yet the feeling of powerlessness persists. Users are simultaneously digital citizens participating in a global public square and the product being sold in a digital marketplace. This section explores this dilemma, critically evaluating the effectiveness of user-facing privacy tools and examining the intricate trade-offs between the competing values of privacy, freedom of expression, and public safety. The analysis will demonstrate that individual "user control" is largely illusory within the current ecosystem and that the contentious debate over content moderation is deeply and inextricably linked to the underlying issues of privacy and surveillance.

6.1 The Illusion of Control?: Evaluating the Efficacy of User-Facing Privacy Settings and Tools

Social media platforms have invested significantly in developing user-facing privacy and security features. These include centralized "Privacy Checkup" tools on platforms like Facebook, which guide users through settings for post visibility, app permissions, and profile information. Users can toggle their accounts between "public" and "private" on Instagram and TikTok, control who can tag them in photos, manage ad preferences, and limit who can send them direct messages. Furthermore, standard security practices like using strong, unique passwords and enabling two-factor authentication (2FA) are strongly encouraged and widely available, providing a crucial layer of defense against unauthorized account access.

Despite this proliferation of tools, a significant "efficacy gap" exists between the control that is promised and the control that is actually delivered. The core problem is that these settings primarily manage content visibility and interpersonal interactions, not the platform's own underlying data collection and processing. A user can meticulously set their posts to be visible only to "close friends," but this does not prevent the platform from scanning the content of those posts, analyzing the images, and using that information to refine the user's advertising profile. The default settings on virtually all platforms are calibrated for maximum data sharing and public visibility, as this is the state that is most profitable for the company. This places the burden of privacy protection squarely on the user, who must be sophisticated, diligent, and proactive enough to navigate complex and often confusing menus to claw back a measure of privacy.

This dynamic creates a powerful "illusion of control". By providing granular settings for managing who sees what, platforms foster a sense of user agency and empowerment. Users feel they are actively managing their privacy, which can placate their concerns. However, the most significant and invasive data practices—the constant collection of behavioral data, the creation of detailed psychological profiles, and the sharing of insights with a vast network of third parties—continue largely unabated in the background. True user control would require not just settings, but genuine transparency about data practices, easy-to-use tools for data portability, and a simple, effective right to deletion. While regulations like the GDPR and CPRA mandate these rights, platforms have at times made them difficult to exercise in practice, as evidenced by user reports of encountering obstacles when trying to access or delete their data.

6.2 A Clash of Rights: Balancing Privacy, Freedom of Speech, and Public Safety

The architecture of social media forces a direct and often contentious confrontation between fundamental rights, particularly the right to privacy and the right to freedom of expression. This tension is not merely philosophical; it plays out daily in the content moderation decisions that shape the digital public square. Strong privacy protections, such as end-to-end encryption and the ability to post anonymously, are vital tools for empowering dissidents, journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens to speak freely without fear of reprisal. They create the necessary space for challenging authority and exploring controversial ideas. However, these same privacy-protective features can be exploited by malicious actors to shield harassment, spread disinformation, incite violence, and distribute illegal material.

This creates a complex balancing act for platforms and policymakers. In the United States, the legal framework adds another layer of complexity. The First Amendment to the Constitution protects individuals from censorship by the government, but it does not apply to content moderation decisions made by private companies like Meta, X, or Google. In a series of landmark cases, including

NetChoice v. Paxton, the U.S. Supreme Court has affirmed that the choices social media platforms make about what content to host, promote, or remove are a form of editorial judgment. As such, these content moderation decisions are themselves a form of expressive conduct protected by the First Amendment.

This legal reality has profound implications. It means that the "modern public square," where much of contemporary political and social discourse takes place, is effectively private property. The owners of this property have a constitutionally protected right to set their own rules for speech. This prevents the government from compelling platforms to host content they deem objectionable, such as forcing them to carry certain political viewpoints. While this protects platforms from state censorship, it concentrates immense power in the hands of a few private companies to regulate global speech. These platforms are incentivized to moderate content not necessarily to foster a healthy public sphere, but to avoid legal liability and maintain an environment that is safe and attractive for advertisers. Their moderation decisions, which are often opaque and inconsistent, are frequently accused of political bias, further eroding public trust.

6.3 Content Moderation as a Privacy Issue: The Intersection of Safety and Surveillance

The act of content moderation is, by its very definition, an act of surveillance. To identify and remove content that violates community standards—whether it be hate speech, violent extremism, child sexual abuse material (CSAM), or disinformation—platforms must first monitor and analyze the content that users post. This creates a direct conflict between the goal of ensuring public safety and the right to private communication and expression. Every message sent, every image uploaded, and every video streamed is potentially subject to inspection by the platform's moderation systems.

This surveillance is carried out through a combination of automated AI tools and teams of human moderators. AI systems can scan massive volumes of content at incredible speed and scale, flagging potentially violative material. However, these systems often struggle with context, nuance, and intent, making them prone to errors. This means that an expert human-in-the-loop is still essential, particularly for adjudicating complex or "borderline" cases. This human review process involves exposing moderators to a relentless stream of the most toxic and traumatic content on the internet, leading to severe mental health consequences, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and highlighting the unsustainable human cost of the current moderation model.

Recognizing this inherent conflict, researchers and civil society groups are urgently calling for the development of privacy-preserving moderation techniques. The goal is to find ways to detect illegal and harmful content without requiring platforms to have full, unencrypted access to all user communications. This is particularly critical for services that offer end-to-end encryption (E2EE), where traditional server-side scanning is impossible. Emerging solutions involve the use of PETs, such as Private Set Intersection (PSI) and Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs), which could allow a user's device to check content against a database of known illegal material (e.g., a hash list of CSAM images) and report a match, without revealing the content itself to the platform. This layered approach, combining on-device intelligence with privacy-preserving server-side verification, offers a potential path forward to achieve safety without sacrificing privacy.

The public debate surrounding content moderation is often framed as a simplistic, binary choice between "free speech" and "safety." This framing, however, is a strategic misdirection that serves the interests of the platforms. By focusing public and political attention on intractable and highly partisan disputes over what specific types of content should be allowed or banned, it conveniently obscures the more fundamental, underlying issue: the unaccountable nature of platform governance. The true threat to a healthy public sphere is not any single moderation decision, but the arbitrary and opaque process by which those decisions are made. Users are frequently "shadow-banned" (their content's visibility is algorithmically reduced without their knowledge), suspended, or de-platformed with no clear explanation, no consistent rules, and no meaningful process for appeal. This lack of procedural justice and due process is a far greater danger than the removal of any particular post. A system built on clear, consistently applied rules, transparent processes, and access to a robust, independent appeals mechanism—as envisioned by regulations like the EU's Digital Services Act —would be inherently more legitimate and trustworthy, regardless of its specific content policies. The current debate keeps the focus on insoluble culture war battles, allowing platforms to avoid accountability for their fundamentally undemocratic governance structures.

Part VII: Reimagining the Future of Digital Privacy

The current paradigm of centralized, surveillance-based social media is facing unprecedented pressure from regulators, users, and technological innovators. This has opened the door to a radical reimagining of the internet's social layer. This final section looks beyond the present-day crisis to explore emerging alternatives and future trajectories. It will critically assess the viability of decentralized social networks and new data stewardship models like data trusts as potential solutions to the privacy crisis. Ultimately, it will synthesize expert analysis to predict the key trends that will define the next decade of digital privacy, forecasting a future characterized by an escalating arms race between surveillance and privacy technologies, strengthening regulatory momentum, and the rise of a hybrid digital ecosystem.

7.1 Beyond Centralization: The Promise and Peril of Decentralized Social Networks

A growing movement aims to re-architect social media by moving away from the centralized model, where a single corporation owns the servers, controls the data, and dictates the rules. Decentralized social networks offer a fundamentally different structure. Some, like Mastodon, are part of the "fediverse"—a federation of thousands of independent, interconnected servers (often called "instances") that can communicate with each other using open protocols like ActivityPub. Others, like Lens Protocol, leverage blockchain technology to create a distributed, user-owned social graph.

The promise of this model is a profound restoration of user privacy and autonomy. In a decentralized system, there is no single entity mining user data for surveillance advertising. Users have genuine ownership of their data and can choose to join a server whose governance and moderation policies align with their own values. Because control is distributed across a global network of independent nodes, these platforms are inherently more resistant to censorship. There is no central "kill switch" and no single corporate entity that can be pressured by a government to de-platform a user or remove content globally. This structure aims to return power from monopolistic corporations to individuals and communities.

However, the path to a decentralized future is fraught with significant practical perils. The very features that make these networks attractive also create formidable challenges.

Scalability and Performance: Decentralized systems, particularly those built on blockchain, often struggle to handle the massive volume of traffic and data processing required to support billions of users, leading to slower performance and a less seamless user experience compared to highly optimized centralized platforms.

Content Moderation: The lack of a central authority makes content moderation a wicked problem. While it prevents top-down censorship, it also creates a risk of the network becoming a haven for unmoderated hate speech, harassment, and illegal content. Moderation is left to the administrators of individual servers, leading to inconsistent enforcement and the potential for harmful content to proliferate.

User Experience and Adoption: Many decentralized platforms are still in their early stages and suffer from cumbersome interfaces, complex onboarding processes (often requiring users to manage cryptographic keys), and a fragmented user experience that can deter mainstream adoption.

Financial Viability: By rejecting the surveillance advertising model, these platforms must find alternative ways to remain financially sustainable, such as relying on donations, user subscriptions, or token-based economies, which can be volatile and less reliable.

7.2 New Models of Stewardship: The Potential of Data Trusts for Social Media Governance

Another visionary approach to solving the privacy crisis involves changing not the technical architecture, but the legal and governance structure of data ownership through the concept of a "data trust." A data trust is a legal framework that separates data use from data collection. In this model, individuals (the beneficiaries) would pool their data rights and place them under the control of an independent, third-party "trustee". This trustee would have a legally binding fiduciary duty to act solely in the best interests of the users.

This model would fundamentally rebalance the power dynamic. Instead of individual users being forced to "consent" to a platform's non-negotiable terms, the platform would have to approach the data trust and request access to the pooled data. The trust, wielding the collective bargaining power of its millions of members, could then negotiate terms of use, purpose limitations, and compensation on their behalf. This would transform users from passive subjects of data extraction into active stakeholders whose interests are represented by a powerful, legally accountable intermediary. Data trusts could enable data sharing for socially beneficial purposes, such as medical research or urban planning, while ensuring that the use aligns with the values and consent of the data subjects.

Like decentralization, however, the data trust model faces significant hurdles to implementation. It is a nascent concept with a host of complex legal and practical challenges.

Legal Frameworks: Many jurisdictions lack a clear legal basis for establishing trusts where the "property" being managed is an intangible right to data. It is also legally unclear in many places whether data rights, such as the GDPR's right to access or erasure, are even transferable to a third-party trustee.

Fiduciary Duty: Defining and enforcing the fiduciary duty of a data trustee is exceptionally complex. What constitutes the "best interest" of millions of diverse beneficiaries, and how would a trustee balance competing interests (e.g., maximizing financial return vs. maximizing privacy)?.

Operationalization and Scale: The practical challenge of creating and operating a legal entity that can effectively represent and manage the data rights of millions of global users, and then successfully negotiate with a corporate goliath like Meta, is immense.

User Uptake: Achieving the critical mass of users needed for a data trust to have meaningful bargaining power would require a massive cultural shift and a level of user engagement in data governance that does not currently exist.

7.3 Expert Analysis and Future Trajectories: Predicting the Next Decade of Digital Privacy

Synthesizing current trends and expert analysis points to several key trajectories that will shape the future of social media privacy over the next decade.

First, privacy will increasingly become a competitive differentiator and a brand imperative. As user awareness grows and regulatory pressures mount, companies will more frequently leverage strong privacy protections as a way to build trust and attract customers. The narrative of privacy as a core feature, not just a compliance burden, will become more common, especially among new market entrants.

Second, the digital world will be defined by an escalating, AI-powered arms race. On one side, AI will enable ever more sophisticated forms of surveillance, profiling, and behavioral prediction. On the other, AI will be essential for developing and deploying the next generation of PETs and for creating more efficient and effective privacy-preserving content moderation systems. The battle between these two applications of AI will be a central dynamic.

Third, the global trend of stronger privacy regulation will continue and intensify. More countries and U.S. states are expected to adopt comprehensive privacy laws modeled on the GDPR or CPRA. Crucially, the focus of these regulations will likely shift from establishing general principles and consent requirements to targeting specific, harmful practices. We can expect more laws aimed directly at regulating surveillance advertising, micro-targeting, and the algorithmic amplification of harmful content.

Finally, the future is unlikely to be a monoculture of either purely centralized or purely decentralized systems. Instead, we are likely to see the emergence of a hybrid digital ecosystem. Large, incumbent platforms will face regulatory pressure to become more open and interoperable—a trend already visible in Meta's decision to allow its Threads platform to connect with the fediverse. They will be forced to cede some control and provide users with more granular power over their algorithmic feeds. Simultaneously, a vibrant ecosystem of niche decentralized platforms will continue to grow, catering to privacy-conscious users and communities with specific interests.

Ultimately, the success or failure of these promising alternative models, such as decentralized networks and data trusts, will not be determined by their technical elegance or philosophical purity. Privacy is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for their success. The core challenge they must overcome is the problem of "governance at scale." The enduring "moat" of today's social media giants is not just their massive network effect; it is their highly evolved, deeply resourced, and globally optimized systems of centralized governance for everything from content moderation and ad delivery to infrastructure management and legal compliance. Any alternative that seeks to displace them must offer a viable, scalable, and resilient model of governance that can provide a safe, stable, and engaging experience for hundreds of millions, if not billions, of users. The future of digital privacy hinges on whether a decentralized or trust-based model can prove it is capable of governing effectively at a global scale.

Part VIII: Strategic Recommendations and Concluding Analysis

The right to privacy on social media stands at a critical juncture. It is a right under siege, eroded by a business model that has successfully transformed personal data into a trillion-dollar commodity. Yet, a powerful counter-movement driven by user awareness, technological innovation, and regulatory will is beginning to reshape the landscape. A sustainable and rights-respecting future for the digital public square is possible, but it requires concerted, strategic action from all stakeholders. This concluding section synthesizes the preceding analysis into a set of actionable recommendations for policymakers, corporations, and digital citizens, followed by a final summary of the report's core arguments.

8.1 A Roadmap for Policymakers: Legislative and Regulatory Imperatives

Governments and regulatory bodies hold the primary responsibility for setting the rules of the road for the digital economy. To effectively protect privacy, they must move beyond outdated frameworks and adopt a more assertive and technologically sophisticated approach.

Move Beyond "Notice-and-Consent" to Prohibiting Harmful Practices: The dominant "notice-and-consent" model has failed. It places an unreasonable burden on individuals to understand complex policies and has been used to legitimize invasive data collection. Regulators should shift their focus to prohibiting specific, inherently harmful practices. This includes banning or severely restricting "surveillance advertising"—the practice of tracking users across websites, apps, and devices to build comprehensive profiles for ad targeting. The CPRA's targeting of "cross-context behavioral advertising" provides a strong legislative model.

Mandate Interoperability and Data Portability to Foster Competition: The immense power of platforms like Meta is sustained by strong network effects; users stay because their friends are there. Policymakers can dismantle these digital monopolies by mandating technical interoperability. This would allow users of different platforms to communicate with each other, much like email users on different providers can. Enforcing robust and easy-to-use data portability rights, as mandated by the GDPR, would further empower users to switch services without losing their social graph and personal data, thereby fostering a more competitive and innovative market.

Create Legal and Financial Support for Privacy-Enhancing Alternatives: Innovation in privacy requires investment. Governments should actively foster the development of a more rights-respecting digital ecosystem by funding research into PETs and new governance models. Creating regulatory "sandboxes" could allow for the responsible testing of emerging concepts like data trusts, providing a safe harbor for experimentation without fear of immediate regulatory action.

Strengthen and Fund Enforcement Agencies: Laws are only as effective as their enforcement. Privacy regulators like the FTC in the U.S. and the ICO in the UK must be equipped with the necessary funding, staffing, and in-house technical expertise to effectively investigate and police the world's most powerful technology companies. This includes the authority to levy fines that are significant enough to act as a genuine deterrent to non-compliance.

8.2 A Call for Corporate Responsibility: Reforming Platform Design and Business Models