Managing Vendor and Third-Party Risks Under GDPR

Learn effective strategies for managing vendor and third-party risks under GDPR. Discover practical approaches to vendor assessment, contractual safeguards, ongoing monitoring, and compliance documentation to protect your organization from data privacy penalties and reputational damage.

The UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR), alongside the Data Protection Act 2018, establishes a stringent legal framework governing the processing of personal data. A central tenet of this framework is the principle of accountability, which holds that organisations are not only responsible for complying with the regulation but must also be able to demonstrate that compliance. This principle extends with undiminished force to situations where an organisation outsources data processing activities to third-party vendors. The relationship between an organisation and its vendors is not merely a commercial arrangement; it is a regulated partnership with clearly defined roles, responsibilities, and liabilities. Understanding this legal foundation is the prerequisite for building any effective vendor risk management program.

1.1 Defining Roles: Distinguishing Between Data Controller and Data Processor

The UK GDPR assigns specific legal roles to the parties involved in data processing, with the primary distinction being between the 'controller' and the 'processor'. This distinction is the fundamental starting point for allocating responsibility and liability in any vendor relationship.

A data controller is defined as the entity that, "alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data". In essence, the controller is the decision-maker. It exercises overall control of the personal data, deciding why the data is being processed (the purpose) and how it will be processed (the means). The controller bears the ultimate responsibility for ensuring the processing complies with the UK GDPR and for demonstrating that compliance. An example would be a hospital that uses an automated system in its waiting room to call patients; the hospital is the controller because it determines the purpose (managing patient flow) and the means (the specific system used).

A data processor, in contrast, is an entity that "processes personal data on behalf of the controller". The processor acts on the controller's instructions and serves the controller's interests rather than its own. It does not own the data or decide the fundamental reasons for its processing. A classic example is a payroll company processing employee salary data on behalf of a client company.

However, this distinction is not always straightforward. Certain professional service providers, such as accountants or lawyers, may act as controllers in their own right even when engaged by a client. This is because their professional obligations may require them to determine the purposes and means of processing independently of their client's instructions, such as reporting malpractice to authorities.

A critical risk for controllers is the potential for a processor to become a "de facto controller." This occurs when a processor acts outside the controller's documented instructions and begins to determine its own purposes and means for processing the data. For instance, if a cloud analytics vendor, hired to process customer data for a specific purpose defined by the controller, starts using that same data to train its own machine learning models for a separate product offering, it has exceeded its mandate. In that moment, for that specific, unauthorized processing, the vendor is no longer a processor. It has become a controller and assumes the full legal liability associated with that role. This creates a significant compliance vulnerability. The original controller may be in breach for failing to have a compliant contract in place and for not adequately overseeing its vendor. Simultaneously, the vendor is now directly exposed to regulatory action, including fines from the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), for its unauthorized processing activities. This underscores the necessity for controllers to not only provide clear instructions but also to actively monitor vendors for any sign of "scope creep" that could alter their legal status and create unforeseen risks.

1.2 The Core Mandate of Article 28: The Principle of Accountability in Outsourcing

Article 28 of the UK GDPR is the cornerstone of vendor risk management. It operationalises the accountability principle for outsourced processing. The article's primary mandate is unambiguous: a controller "shall use only processors providing sufficient guarantees to implement appropriate technical and organisational measures" to ensure the processing meets the requirements of the UK GDPR and protects the rights of data subjects.

This is not a passive requirement. The onus is placed squarely on the controller to proactively vet and select vendors that can demonstrate their capability and reliability. The ICO's guidance clarifies that this involves assessing a potential processor's "expert knowledge, resources and reliability". The controller's responsibility under Article 24 to implement measures that ensure and demonstrate compliance is directly fulfilled, in part, by its diligent selection and management of processors.

Furthermore, Article 28 dictates that the relationship must be governed by a binding written contract or other legal act. This contract, commonly known as a Data Processing Agreement (DPA), is the primary legal instrument for defining the roles, responsibilities, and specific obligations of both parties. The failure to have a compliant Article 28 contract in place is, in itself, a breach of the UK GDPR. Therefore, the selection of a vendor and the execution of a compliant DPA are foundational, non-delegable responsibilities of the data controller.

1.3 Processor Liability: Direct Obligations Under UK GDPR

One of the most significant shifts introduced by the GDPR framework was the imposition of direct statutory obligations and liabilities upon data processors. Prior to the GDPR, processors were typically only liable to the controller under the terms of their contract. The UK GDPR changed this landscape fundamentally, making processors directly accountable to regulatory authorities for certain obligations.

Processors now have a range of direct responsibilities under the law, including:

Processing only on the controller's documented instructions.

Implementing appropriate technical and organisational security measures to protect personal data, as required by Article 32.

Notifying the controller of a personal data breach "without undue delay" after becoming aware of it.

Appointing a data protection officer (DPO) in certain circumstances.

Maintaining records of processing activities.

Complying with the rules on international data transfers.

Cooperating with supervisory authorities like the ICO during investigations.

Crucially, a processor's failure to meet these obligations can lead to direct enforcement action, including investigations, corrective orders, and significant administrative fines from the ICO. This represents the end of the "processor shield," where vendors could operate with a degree of insulation from regulatory scrutiny.

For years, this direct liability was largely a theoretical risk, as ICO enforcement actions tended to focus on data controllers. However, this changed with the landmark fine issued against Advanced Computer Software Group Ltd in March 2025. The ICO fined the software provider, an NHS data processor, over £3 million for security failings that led to a ransomware attack. This was the first monetary penalty issued by the ICO directly against a data processor under the UK GDPR for a breach of its security obligations.

This enforcement action has profound implications for the vendor ecosystem. It operationalises the direct liability of processors, confirming that the ICO will investigate and penalise entities throughout the data supply chain for their own compliance failures. This fundamentally alters the dynamic of contract negotiations. Processors can no longer view GDPR clauses as a matter of passing liability back to the controller; they must now account for their own direct regulatory and financial risk. This shift empowers controllers to demand more robust security commitments, greater transparency, and more extensive audit rights, as they can now point to the processor's own direct legal jeopardy as a compelling reason for these measures.

The Due Diligence Imperative: Vetting and Onboarding Vendors

The Article 28 mandate to use only processors providing "sufficient guarantees" necessitates a robust and documented due diligence process. This is not a mere formality but a critical risk management function that must be performed before any personal data is shared and a contract is signed. Effective due diligence provides the controller with the assurance that a potential vendor has the necessary policies, procedures, and technical controls in place to protect personal data in line with UK GDPR requirements.

2.1 Establishing a Risk-Based Due Diligence Framework

A one-size-fits-all approach to vendor due diligence is both inefficient and ineffective. The level of scrutiny applied to a potential vendor should be proportionate to the risks associated with the processing activity they will undertake. A risk-based framework allows an organisation to allocate its resources effectively, focusing the most intensive efforts on the highest-risk relationships.

The first step in this framework is to create a comprehensive inventory of all third-party vendors and classify them by risk level. This classification should be based on factors such as the volume of personal data to be processed, the sensitivity of that data (e.g., special category data like health information), the nature of the processing (e.g., large-scale monitoring), and the criticality of the vendor's service to the business's operations. A practical model involves tiering vendors into categories :

Tier 1 (High Risk): Business-critical vendors processing large volumes of sensitive personal data. Examples include cloud hosting providers, payroll platforms, or healthcare data analytics services. These vendors require the most stringent due diligence, including in-depth questionnaires, evidence review, and potentially on-site audits.

Tier 2 (Moderate Risk): Vendors processing less sensitive personal data or in smaller volumes, or those providing less critical services. Examples could include marketing agencies or recruitment partners. Due diligence would still be thorough but may rely more on questionnaires and certification reviews.

Tier 3 (Low Risk): Vendors with minimal or no access to personal data. Examples include office stationery suppliers or catering services. A much lighter-touch due diligence process is appropriate for this tier.

Once a framework is established, clear internal ownership must be assigned. This is a cross-functional responsibility, typically involving :

Procurement: Managing the vendor selection and commercial terms.

Compliance/Legal/DPO: Overseeing the legal and regulatory aspects, including GDPR compliance checks.

IT Security/CISO: Assessing the vendor's cybersecurity posture, technical controls, and infrastructure.

Finance: Evaluating the vendor's financial stability and viability.

This structured, risk-based approach ensures that due diligence is not only compliant but also a valuable and efficient part of the overall procurement and risk management lifecycle.

2.2 Conducting Effective Pre-Contractual Assessments: Questionnaires and Evidence

The primary tool for conducting due diligence is a detailed assessment questionnaire. However, to be effective, this questionnaire must be designed to elicit specific, verifiable information, not just boilerplate attestations. The goal is to move beyond a trust-based model to an evidence-based one.

A comprehensive UK GDPR due diligence questionnaire should cover key compliance domains, including :

Overall Governance: Does the vendor have a formal data protection program? Is there a designated DPO or an individual with clear responsibility for data protection?

Data Handling Practices: Where will the data be stored and processed? Does the vendor have a plan for identifying, mapping, and recording data flows?

Legal Basis and Transparency: How will the vendor ensure that processing is only performed for the purposes instructed by the controller?

Security Measures: What specific technical and organisational measures (TOMs) are in place (e.g., encryption, access controls, resilience and recovery processes)?

Sub-processing: Does the vendor use sub-processors? If so, what is the process for vetting them and ensuring contractual flow-down of obligations?

International Transfers: If data will be transferred outside the UK, what legal mechanisms are in place to ensure its protection?

Data Subject Rights: What processes does the vendor have to assist the controller in fulfilling requests from data subjects (e.g., for access or erasure)?

Breach Management: What is the vendor's incident response and data breach notification plan?

For each question, the controller should request supporting documentary evidence. This could include copies of the vendor's data protection policy, information security policy, incident response plan, recent penetration test results, staff training records, or relevant certifications. This evidence-based approach is crucial for demonstrating to the ICO that the controller has taken concrete steps to verify the "sufficient guarantees" offered by the vendor.

2.3 The Role of Certifications and Codes of Conduct

While not a substitute for thorough due diligence, adherence to approved certification schemes or codes of conduct can serve as a key element in demonstrating a vendor's compliance posture. The UK GDPR explicitly states in Article 28 that such adherence may be used as a factor in demonstrating sufficient guarantees.

The most widely recognised and relevant certification in this context is ISO/IEC 27001, the international standard for Information Security Management Systems (ISMS). While ISO 27001 is a security standard, not a data protection standard, its comprehensive framework of controls provides a strong foundation for meeting the technical and organisational security requirements of UK GDPR's Article 32. Many due diligence questionnaires specifically ask whether a vendor holds an ISO 27001 certification. For certain public sector engagements, such as with the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), a valid ISO 27001 certificate is explicitly accepted as evidence of adequate security assurances.

When a vendor provides a certification like ISO 27001, the controller should still verify its authenticity and scope. This includes checking that the certificate was issued by an accredited body (e.g., UKAS-accredited in the UK) and that the scope of the certification covers the specific services, systems, and locations that will be used for processing the controller's data. A certificate with a very narrow scope may not provide the required level of assurance.

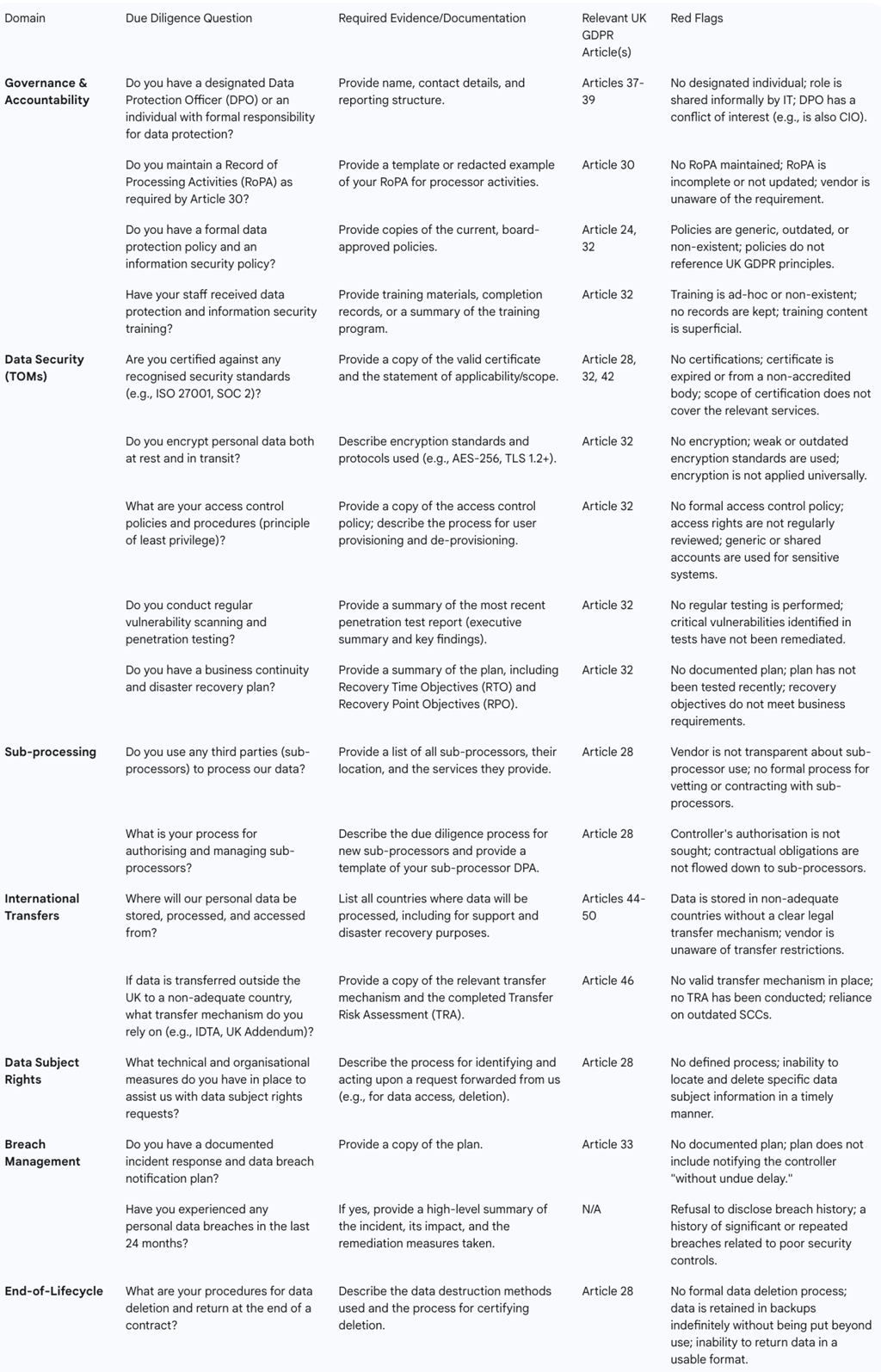

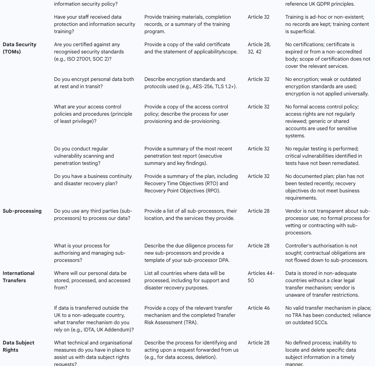

Table 1: Comprehensive Vendor Due Diligence Checklist (UK GDPR)

The following table synthesises best practices into a comprehensive checklist for conducting vendor due diligence under the UK GDPR. It is designed to be a practical tool for compliance, legal, and security teams, moving beyond simple questions to demand specific evidence for verification.

The Data Processing Agreement (DPA): Your Primary Contractual Safeguard

While due diligence assesses a vendor's capabilities, the Data Processing Agreement (DPA) legally binds them to their data protection obligations. Under Article 28(3) of the UK GDPR, any processing carried out by a processor on behalf of a controller must be governed by a contract or other binding legal act. This is not an optional best practice; it is a strict legal requirement. The DPA serves as the primary contractual safeguard, translating the principles of the UK GDPR into enforceable terms and providing the controller with a legal basis for holding the processor accountable.

3.1 Anatomy of an Article 28-Compliant DPA

A compliant DPA must be in writing (which can include electronic form) and must contain specific, mandated information. The ICO's guidance breaks this down into two main categories of required content.

First, the DPA must set out the fundamental details of the processing arrangement, providing clarity and context for the relationship. These details include :

The subject-matter and duration of the processing: What the processing is about (e.g., "Provision of cloud-based HR management services") and for how long it will last (e.g., "For the duration of the Master Services Agreement").

The nature and purpose of the processing: The 'how' and 'why' of the processing (e.g., "Nature: Storing, organising, and providing access to employee data. Purpose: To enable the controller to manage its human resources functions").

The type of personal data and categories of data subject: The specific data elements involved (e.g., "Name, address, contact details, salary information, performance reviews") and the individuals the data relates to (e.g., "Current, former, and prospective employees of the controller").

The controller's obligations and rights: A high-level statement of the controller's responsibilities, which are then detailed through the mandatory clauses.

Second, beyond these contextual details, Article 28(3) mandates the inclusion of a series of specific terms and clauses that impose direct data protection obligations on the processor. These clauses are the core of the DPA and are non-negotiable for compliance.

3.2 Dissecting Mandatory Clauses: From Documented Instructions to Audit Rights

Each mandatory clause in a DPA serves a distinct purpose in ensuring the protection of personal data and upholding the controller's oversight. A detailed examination of these clauses reveals the mechanics of an Article 28-compliant relationship.

Processing only on documented instructions (Article 28(3)(a)): The DPA must state that the processor will only process personal data on the controller's documented instructions. This clause is the primary legal mechanism that ensures the controller retains ultimate control over the data. It prevents the processor from using the data for its own purposes and is the key safeguard against the "de facto controller" risk.

Duty of confidence (Article 28(3)(b)): The agreement must require the processor to ensure that any person it authorises to process the data (e.g., employees, contractors) is subject to a strict duty of confidentiality.

Appropriate security measures (Article 28(3)(c)): The processor must contractually commit to implementing the "appropriate technical and organisational measures" required by Article 32 to ensure the security of the data. This often involves referencing specific security standards or practices.

Using sub-processors (Article 28(3)(d)): This is a critical clause for managing the supply chain. The DPA must state that the processor will not engage another processor (a sub-processor) without the controller's prior specific or general written authorisation. If a sub-processor is engaged, the processor must impose the same data protection obligations on that sub-processor via a written contract. Crucially, the initial processor remains fully liable to the controller for the performance of the sub-processor's obligations.

Data subjects' rights (Article 28(3)(e)): The processor must agree to assist the controller, through appropriate technical and organisational measures, in responding to requests from individuals exercising their rights under the UK GDPR (e.g., the right of access, rectification, or erasure).

Assisting the controller (Article 28(3)(f)): The DPA must oblige the processor to assist the controller in ensuring compliance with its own obligations under Articles 32 to 36. This includes assistance with data security, personal data breach notifications to the ICO and data subjects, and the completion of Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs).

End-of-contract provisions (Article 28(3)(g)): At the termination of the contract, the processor must, at the controller's choice, either delete or return all personal data. The processor must also delete all existing copies unless required by law to retain them. This ensures that the controller retains control over the data's lifecycle even after the commercial relationship has ended.

Audits and inspections (Article 28(3)(h)): The DPA must require the processor to make available to the controller all information necessary to demonstrate compliance with Article 28. It must also allow for and contribute to audits, including inspections, conducted by the controller or an auditor mandated by the controller. This right to audit is the controller's ultimate verification tool.

3.3 The Use of Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) Issued by the ICO

To simplify compliance, the UK GDPR allows the ICO to issue standard contractual clauses (also known as SCCs) for use in DPAs. If these pre-approved clauses are incorporated into a contract between a controller and a processor without amendment, the agreement should be considered compliant with the requirements of Article 28(3).

The availability of these standard clauses presents a strategic choice for organisations. On one hand, they offer a "safe harbour"—a straightforward and regulator-approved method to ensure baseline legal compliance, which can be particularly efficient for engaging with low-risk or smaller vendors. It reduces the time and legal costs associated with drafting and negotiating bespoke agreements.

On the other hand, large, sophisticated vendors, particularly in the technology sector (e.g., major cloud service providers), will almost invariably insist on using their own standard DPA. These agreements are designed for scalability and are often presented on a non-negotiable basis. This can create a point of friction, as the controller's legal team must then conduct a thorough analysis to ensure the vendor's DPA contains all the mandatory elements of Article 28.

This situation reveals a trade-off between compliance simplicity and commercial reality. While ICO-issued clauses guarantee Article 28 compliance, they may not address specific commercial risks that are important to the controller, such as liability caps, indemnities for non-GDPR related losses, specific service-level agreements for breach notification, or intellectual property rights. A vendor's standard DPA, conversely, will be drafted to be favourable to the vendor on these commercial points.

Therefore, the most effective strategy often involves using the ICO's standard clauses as a benchmark. For low-risk vendor relationships, adopting the standard clauses wholesale may be the most efficient path. For high-risk, business-critical vendors, a bespoke DPA is often necessary. In these negotiations, the ICO's clauses serve as the non-negotiable baseline for data protection obligations, on top of which the parties can layer more specific commercial terms, liability provisions, and operational details. The existence of the standard clauses thus elevates the negotiation, ensuring that the fundamental data protection requirements are met before commercial considerations are even discussed.

Navigating International Data Transfers

In an increasingly globalised economy, it is common for data processing to occur across borders. The UK GDPR places strict controls on the transfer of personal data to vendors and third parties located outside the United Kingdom. These rules are designed to ensure that the high level of protection afforded to personal data under UK law is not undermined when that data leaves the country. Navigating this landscape, which has been significantly shaped by Brexit and the landmark Schrems II judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), is a critical component of vendor risk management.

4.1 Understanding "Restricted Transfers" Post-Brexit

Following its departure from the European Union, the UK adopted the EU GDPR into its own legal framework, creating the UK GDPR. This established the UK as a separate jurisdiction for data protection purposes, with its own rules governing transfers of personal data to other countries.

A "restricted transfer" under the UK GDPR occurs when the following three conditions are met :

The UK GDPR applies to the processing of the personal data being transferred.

The data is being sent or made accessible to a receiver located in a country outside the UK.

The receiver is a legally distinct entity from the sender (e.g., a separate company, even within the same corporate group).

It is important to note that the simple transit of data through servers in another country does not necessarily constitute a restricted transfer, provided there is no intention for the data to be accessed or manipulated while in that country. The rules apply when data is being transferred for processing by a distinct legal entity in another jurisdiction.

4.2 Mechanism 1: Adequacy Regulations

The simplest and most straightforward mechanism for making a restricted transfer is to send the data to a country, territory, or sector that is covered by the UK's "adequacy regulations". An adequacy decision signifies that the UK government has assessed the legal framework in the destination country and determined that it provides a level of data protection that is "essentially equivalent" to that of the UK.

If a vendor is located in a country with a UK adequacy decision, personal data can be transferred to them without the need for any additional safeguards, such as contractual clauses. The transfer is treated as if it were taking place within the UK.

The UK has deemed all countries within the European Economic Area (EEA) and Gibraltar to be adequate, allowing for the free flow of data from the UK to these territories. Reciprocally, the European Commission has granted adequacy decisions to the UK, permitting data to flow from the EEA to the UK. The UK government maintains and updates a list of all countries, territories, and sectors covered by its adequacy regulations.

4.3 Mechanism 2: Appropriate Safeguards - The IDTA and the UK Addendum

When transferring data to a vendor in a country that is not covered by an adequacy decision (a "non-adequate" country), the controller must put in place one of the "appropriate safeguards" listed in Article 46 of the UK GDPR. For most commercial relationships, the most relevant safeguards are legally binding contractual agreements.

Following Brexit and the Schrems II ruling, the ICO has issued two primary contractual tools for this purpose :

The International Data Transfer Agreement (IDTA): This is a standalone, UK-specific contract designed to be used for restricted transfers of personal data from the UK to non-adequate countries. It contains all the necessary contractual obligations on both the data exporter (the UK entity) and the data importer (the vendor) to ensure the protection of the transferred data.

The UK Addendum to the EU Standard Contractual Clauses (the Addendum): Many multinational organisations transfer data from both the UK and the EU. To avoid the need for two separate contracts, the ICO created the Addendum. This is a short, supplementary document that is appended to the EU's own Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). The Addendum makes targeted amendments to the EU SCCs to make them legally valid for restricted transfers under the UK GDPR. This allows organisations to use a single, familiar contractual base (the EU SCCs) for both their EU and UK data exports, simply by attaching the UK Addendum where necessary.

Organisations have the flexibility to choose between using the standalone IDTA or the EU SCCs with the UK Addendum to legitimise their restricted transfers. Any contracts for new transfers initiated after 21 September 2022 must use one of these new instruments, and all existing arrangements based on the old, pre-Brexit EU SCCs were required to be replaced by 21 March 2024.

4.4 The Transfer Risk Assessment (TRA): The Post-Schrems II Obligation

The use of an Article 46 safeguard, such as the IDTA or the Addendum, is a necessary but not sufficient step. The 2020 Schrems II judgment fundamentally changed the international data transfer landscape. The CJEU ruled that data exporters cannot simply rely on the existence of a contract; they must also verify, on a case-by-case basis, that the laws and practices of the destination country do not impinge on the effectiveness of the safeguards contained within that contract. In particular, this involves assessing the risk of public authorities (e.g., intelligence agencies) in the destination country being able to access the data in a manner that is not compliant with EU (and now UK) fundamental rights standards.

This obligation to conduct a risk assessment is now an integral part of making a restricted transfer under the UK GDPR. This assessment is known as a Transfer Risk Assessment (TRA). The TRA must be conducted

before the transfer takes place and must be documented.

Recognising the complexity this creates for organisations, the ICO has issued its own guidance and a TRA tool to provide a structured methodology for this assessment. The ICO's approach is notably more pragmatic and risk-based than that of its EU counterparts, such as the European Data Protection Board (EDPB). The ICO's TRA process involves considering the specific circumstances of the transfer and, crucially, the level of risk to individuals in the personal data being transferred.

A key element of the ICO's guidance is the concept of a "low harm risk" transfer. If, after an initial assessment, the data being transferred is deemed to be of low risk (e.g., it is unlikely to cause more than inconsequential harm if misused, such as basic business contact details), the ICO's guidance suggests that the transfer may be able to proceed without a detailed analysis of the destination country's legal and surveillance framework. This represents a significant divergence from the more rigid approach often advocated in the EU and provides a more proportionate pathway for UK organisations undertaking low-risk data transfers.

For transfers involving higher-risk data, a full TRA is required, assessing whether the IDTA or Addendum will be enforceable in the destination country and whether there is appropriate protection from third-party access by public authorities. If the TRA concludes that the risks in the destination country undermine the contractual safeguards, the transfer cannot proceed unless supplementary measures (e.g., enhanced technical encryption) are put in place to mitigate those risks. This entire process must be carefully documented to demonstrate compliance to the ICO.

From Contract to Compliance: Ongoing Monitoring and Auditing

Executing a compliant DPA and conducting initial due diligence are foundational steps, but they mark the beginning, not the end, of the vendor management lifecycle. The principle of accountability under the UK GDPR requires controllers to ensure that their processors remain compliant throughout the duration of the relationship. This necessitates a structured program of ongoing monitoring, auditing, and oversight. As legal experts have noted, a controller cannot simply "sign a compliant contract then forget about it". Compliance is a continuous exercise, not a one-off event.

5.1 Establishing a Continuous Vendor Oversight Program

An effective vendor oversight program moves beyond periodic, point-in-time assessments to a model of continuous monitoring. The goal is to maintain an up-to-date understanding of a vendor's security and compliance posture and to identify emerging risks before they escalate into incidents.

A modern approach to this involves leveraging technology to automate the monitoring process. Continuous vendor security monitoring platforms can provide dynamic, real-time insights into a vendor's cybersecurity performance by scanning their external security posture for vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and other indicators of risk. These tools can track a vendor's security hygiene over time, detect data breaches or credential leaks on the dark web, and automate the tracking of compliance with regulatory frameworks.

The frequency and intensity of monitoring should align with the risk-based framework established during due diligence. High-risk vendors that handle sensitive data or provide critical services should be subject to more frequent and stringent oversight, such as quarterly reviews or continuous automated monitoring. Lower-risk vendors may only require an annual review or reassessment upon contract renewal.

The program should also include regular reviews of the DPA to ensure it remains aligned with any changes in the law or in the nature of the processing activities. Contracts should be revisited at least annually, or whenever there is a significant change in the vendor relationship.

5.2 Practical Methodologies for Audits and Inspections

The right to audit, which must be included in the DPA under Article 28(3)(h), is the controller's most powerful tool for verification. This right must be operationalised through a clear and practical audit methodology. The scope and nature of an audit can vary depending on the vendor's risk level and may include a combination of the following activities:

Documentation Review: The most common form of audit involves requesting and reviewing the vendor's key compliance documentation. This includes their data protection policies, information security policies, staff training records, RoPA, recent risk assessments, and reports from any third-party security audits or certifications (e.g., ISO 27001 or SOC 2 reports).

Questionnaire-Based Audits: Sending a detailed annual or biennial questionnaire to the vendor to attest to their ongoing compliance with the terms of the DPA and the UK GDPR.

Review of System Logs: For high-risk processing, the controller may request access to review relevant system and access logs to verify that data is being accessed only by authorised personnel for legitimate purposes.

On-site Inspections: While more resource-intensive and often reserved for the most critical, high-risk vendors, the right to conduct on-site inspections of the vendor's premises and security controls is a key contractual safeguard. This allows the controller (or a mandated third-party auditor) to physically verify the implementation of the security measures described in the vendor's policies.

The results of all monitoring and auditing activities must be documented. Any identified deficiencies or non-conformities should be formally tracked, and a remediation plan with clear timelines should be agreed upon with the vendor.

5.3 Managing the Fourth-Party Risk: Sub-Processor Control

The data processing chain often extends beyond the primary vendor (the processor) to other organisations they engage (sub-processors). This introduces "fourth-party risk," and under the UK GDPR, the controller retains ultimate responsibility for the entire chain.

Article 28 places strict controls on the use of sub-processors. A processor is prohibited from engaging a sub-processor without the controller's "prior specific or general written authorisation".

Specific Authorisation: The controller must approve each individual sub-processor before they are engaged.

General Authorisation: The controller gives upfront approval for the processor to engage sub-processors, provided the processor informs the controller of any intended changes (additions or replacements), giving the controller an opportunity to object.

Regardless of the authorisation model used, the processor must have a written contract with the sub-processor that imposes the same data protection obligations as those set out in the DPA between the controller and the processor. This contractual flow-down is essential.

Crucially, Article 28(4) states that the initial processor remains "fully liable to the controller for the performance of that other processor's obligations". This means the controller has a direct line of contractual recourse to its primary vendor for any failures by a sub-processor.

Effective management of this risk requires controllers to:

Demand Transparency: During due diligence, require a full list of all sub-processors that will be involved in processing the data.

Exercise Authorisation Rights: Carefully consider whether to grant specific or general authorisation. General authorisation is more operationally convenient for the processor, but specific authorisation gives the controller greater control.

Audit the Sub-processor Vetting Process: As part of ongoing monitoring, review the processor's due diligence process for its own sub-processors to ensure it is sufficiently robust.

Maintain an Up-to-Date List: Require the processor to maintain and provide an up-to-date list of all sub-processors and to provide timely notification of any changes.

Failure to maintain visibility and control over the sub-processing chain is a significant compliance gap and has been identified as a key risk area leading to regulatory fines.

Crisis Management: Responding to a Vendor-Related Data Breach

Despite robust due diligence and contractual safeguards, data breaches can and do occur. When a vendor experiences a personal data breach that affects a controller's data, a swift, coordinated, and compliant response is critical to mitigate harm to individuals and meet regulatory obligations. The UK GDPR establishes a clear sequence of events and responsibilities for both the processor and the controller in such a scenario.

6.1 Allocation of Responsibilities: The Processor's Duty to Notify

The breach response process is initiated by the party that first discovers the incident. If a processor experiences a breach affecting the data it processes on behalf of a controller, its primary legal obligation is to inform the controller.

Article 33(2) of the UK GDPR mandates that a processor must notify the data controller "without undue delay after becoming aware of a personal data breach". This is a direct statutory duty placed upon the processor. The term "without undue delay" is not explicitly defined in hours, but it is understood to mean as soon as is practically possible. To ensure the controller has sufficient time to meet its own reporting deadlines, many DPAs will contractually specify a much shorter timeframe for this notification, such as 24 or 48 hours.

The processor's notification to the controller should contain, at a minimum, the details of the breach that are known at the time, enabling the controller to begin its own assessment and response process. The ultimate responsibility for assessing the breach's severity and notifying the regulatory authorities and affected individuals rests with the controller.

6.2 The Controller's Response and the 72-Hour Deadline to Notify the ICO

Once the controller becomes aware of a personal data breach—either through notification from its processor or through its own discovery—a strict timeline for regulatory notification begins.

Under Article 33(1), a controller must report a notifiable personal data breach to the ICO "without undue delay and, where feasible, not later than 72 hours after having become aware of it". This 72-hour deadline is absolute and includes weekends and public holidays; it does not differentiate between working and non-working hours.

A breach is "notifiable" if it is "likely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons". This requires the controller to make a rapid risk assessment. If the breach is unlikely to pose such a risk (e.g., the loss of a securely encrypted and backed-up dataset where the key was not compromised), notification to the ICO is not required. However, the controller must document this decision and the reasoning behind it as part of its accountability obligations.

The notification to the ICO must include specific information :

A description of the nature of the breach, including the categories and approximate number of data subjects and personal data records concerned.

The name and contact details of the DPO or other contact point.

A description of the likely consequences of the breach.

A description of the measures taken or proposed to be taken by the controller to address the breach and mitigate its adverse effects.

If it is not possible to provide all this information within the 72-hour window, the controller can provide it in phases "without undue further delay," but the initial notification must still be made within the deadline.

6.3 Communicating with Data Subjects: The "High Risk" Threshold

In addition to notifying the ICO, the controller has a separate obligation to consider whether to communicate the breach directly to the affected individuals. This requirement is triggered by a higher risk threshold than the one for notifying the ICO.

Under Article 34, if a personal data breach is "likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons," the controller must communicate the breach to the affected data subjects "without undue delay". A "high risk" implies a greater severity of potential harm. For example, a breach involving financial data, sensitive health information, or data that could lead to identity theft would likely meet this threshold, whereas the loss of a simple customer marketing list might not.

The assessment of risk should consider factors such as the type of breach, the nature and sensitivity of the data, the severity of the potential consequences for individuals, and any particular vulnerabilities of the affected data subjects.

The communication to individuals must be in clear and plain language and describe the nature of the breach, its likely consequences, and the measures being taken. If a controller decides that a breach is not "high risk" and therefore does not notify individuals, it must still document this assessment. It is important to note that the ICO has the power to review this decision and can compel an organisation to inform individuals if it disagrees with the controller's risk assessment.

The Consequences of Failure: ICO Enforcement and Case Law

The obligations for managing vendor and third-party risk under the UK GDPR are not merely theoretical principles. The ICO has a wide range of enforcement powers to address non-compliance, and a growing body of case law demonstrates a clear focus on failures within the data supply chain. These enforcement actions provide invaluable lessons on the tangible consequences of inadequate vendor management, moving the discussion from legal text to real-world financial and reputational impact. The ICO can issue reprimands, enforcement notices, and, most significantly, monetary penalties of up to £17.5 million or 4% of an undertaking's total annual worldwide turnover, whichever is higher.

7.1 Analysis of ICO Fines and Reprimands in Vendor-Related Incidents

An analysis of ICO enforcement actions reveals that third-party failures are a recurring theme. Breaches often originate not within the controller's own systems but from vulnerabilities introduced by vendors, suppliers, or other partners. These incidents highlight that from the regulator's perspective, accountability is not diluted by outsourcing; the controller remains firmly responsible for the security of the data throughout its lifecycle.

The ICO's enforcement trends show a willingness to use its full range of powers to address these failures. While headline-grabbing fines are the most visible tool, the ICO also frequently issues reprimands and enforcement notices that require organisations to take specific remedial actions to improve their data protection practices. These actions serve as a cautionary signal to the wider industry about the potential consequences of non-compliance.

7.2 Landmark Case Study: Advanced Computer Software Group Ltd

The ICO's decision to fine Advanced Computer Software Group Ltd (Advanced) over £3 million in March 2025 is arguably the most significant enforcement action to date concerning vendor risk in the UK. As the first monetary penalty levied directly against a data processor for a security breach, it sets a powerful precedent.

The Failure: Advanced, a key IT provider to the NHS, suffered a ransomware attack in August 2022. The ICO's investigation found that attackers gained access to Advanced's systems via a customer account that was not protected by multi-factor authentication (MFA). This failure to implement a fundamental and widely expected security control across its entire estate was deemed a serious breach of Advanced's direct obligations under Article 32 of the UK GDPR.

The Impact: The attack resulted in the exfiltration of personal data belonging to nearly 80,000 people, including highly sensitive medical information and, in some cases, details on how to gain physical access to patients' homes. The breach also caused severe disruption to NHS services, including the 111 advice line.

Key Learnings:

Direct Processor Liability is Real: This case confirms that data processors are directly in the ICO's enforcement crosshairs and can face multi-million-pound fines for their own security failings.

Security Fundamentals are Non-Negotiable: The failure to implement a basic control like comprehensive MFA on systems processing large volumes of sensitive data was a key factor in the ICO's decision. This signals that a failure to adhere to established cybersecurity best practices will be viewed as a clear violation.

Cooperation Can Mitigate Fines: The initial proposed fine was significantly higher at £6.09 million. The ICO reduced the final penalty in part due to Advanced's "proactive engagement" with the NCSC, law enforcement, and the NHS, as well as the steps it took to mitigate the harm. This highlights the value of a transparent and cooperative post-breach response.

7.3 Case Study: Ticketmaster

The £1.25 million fine issued to Ticketmaster UK Limited demonstrates that vendor risk extends beyond core data processors to any third-party component integrated into an organisation's systems.

The Failure: The breach originated from a third-party-hosted chatbot script running on Ticketmaster's online payment page. Attackers compromised the chatbot, allowing them to skim the payment card details of millions of customers over several months. The ICO found that Ticketmaster had failed to assess the risks associated with this third-party script and was too slow to react to multiple warnings from financial institutions about potential fraud.

Key Learnings:

Vendor Risk Includes Third-Party Code: Due diligence must extend to all third-party components, scripts, and plugins integrated into websites and applications, especially on sensitive pages like payment gateways. The risk of so-called "shadow vendors" is significant.

Timely Response is Crucial: Ticketmaster's nine-week delay in investigating the source of the fraud after being alerted was a key factor in the ICO's decision. Organisations must have processes to promptly investigate and act upon indicators of a potential breach.

Controllers are Accountable for their Ecosystem: Ticketmaster, as the controller, was held responsible for the security failure of a component supplied by a third party.

7.4 Case Study: British Airways

The data breach at British Airways, which initially resulted in a proposed fine of £183 million (later reduced to £20 million), originated from a compromise at a third-party supplier.

The Failure: Attackers compromised the login credentials of a third-party supplier that had remote access to British Airways' network. From this foothold, they were able to access and exfiltrate the personal and payment card data of approximately 500,000 customers. The ICO's investigation highlighted failures in implementing appropriate security measures, including limited visibility into its partner ecosystem and inadequate access controls.

Key Learnings:

Least Privilege Access for Vendors is Critical: A third-party supplier should never have a level of access that could lead to a catastrophic compromise of core customer data systems. The principle of least privilege—granting only the minimum access necessary for a vendor to perform its function—is paramount. This echoes the lessons from other major third-party breaches, where the compromise of a vendor with overly permissive access (such as an HVAC provider) led to a major data breach.

Robust Identity and Access Management is Essential: Effective vendor risk management requires stringent controls over third-party identities, credentials, and access pathways into the corporate network.

These cases collectively illustrate that the ICO takes a broad view of vendor risk and will hold organisations accountable for failures anywhere in their data supply chain. A proactive, risk-based, and continuously monitored vendor management program is the only effective defence against such regulatory action.

Strategic Recommendations and Best Practices

Managing vendor and third-party risk under the UK GDPR is not merely a legal-box-ticking exercise; it is a strategic imperative that requires the integration of legal compliance, cybersecurity best practices, and robust operational processes. A successful program moves beyond a reactive, contract-centric approach to a proactive, risk-based lifecycle management of the entire vendor ecosystem. This concluding section synthesises the report's findings into actionable recommendations, drawing on established international frameworks to provide a blueprint for excellence in vendor risk management.

8.1 Synthesizing Best Practices from ISO 27001, NIST, and ENISA

While the UK GDPR sets out the legal obligations ('the what'), globally recognised frameworks from organisations like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) provide the operational methodologies ('the how'). Leveraging these frameworks allows an organisation to build a defensible and effective program that demonstrates the "appropriate technical and organisational measures" required by law.

ISO/IEC 27001: This standard for an Information Security Management System (ISMS) provides a comprehensive, risk-based framework for managing information security. Its Annex A controls, particularly those related to supplier relationships (now clauses 5.19 to 5.23 in the 2022 version), directly map to the requirements of GDPR vendor management. Implementing an ISO 27001-compliant process for vendor selection, contracting, monitoring, and offboarding provides a structured and auditable method for managing vendor security risk. Furthermore, as noted in Article 28, an ISO 27001 certification can be used by a vendor as a key piece of evidence to demonstrate that it provides "sufficient guarantees".

NIST Frameworks: The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) and Risk Management Framework (RMF) are highly respected, globally adopted standards for managing cybersecurity risk. They are valuable because they provide a common language and structured process for identifying, assessing, and responding to risks. Crucially, the updated NIST RMF explicitly incorporates "supply chain risk management considerations," making it directly applicable to managing vendor risk in a GDPR context. Aligning a vendor risk program with the NIST CSF's functions (Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover) ensures a holistic approach that covers the entire incident lifecycle.

ENISA Guidance: As the EU's cybersecurity agency, ENISA provides detailed, practical guidance on supply chain cybersecurity. It advocates for a continuous improvement model based on the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle, which involves a recurring process of risk assessment, supplier relationship management, vulnerability handling, and quality assurance. This cyclical approach aligns perfectly with the GDPR's requirement for ongoing monitoring and review of vendor relationships.

The clear convergence of data protection law with these established cybersecurity frameworks illustrates a critical point: modern vendor risk management is an integrated discipline. It requires a fusion of legal, compliance, and IT security expertise. A Data Protection Officer must understand the security controls within ISO 27001, and a Chief Information Security Officer must grasp the legal implications of a sub-processor clause in a DPA. The most mature and effective Third-Party Risk Management (TPRM) programs are those that break down these internal silos and use these frameworks as a common language to manage risk holistically.

8.2 Implementing a Tiered, Risk-Based Approach to Vendor Management

As detailed throughout this report, a proportionate, risk-based approach is the most effective and efficient way to manage a diverse vendor portfolio. The practical implementation of this strategy involves a continuous cycle:

Create and Maintain a Vendor Inventory: Establish a central, up-to-date inventory of all third-party vendors, noting the data they access and the services they provide.

Classify Vendors by Risk: Tier all vendors (e.g., High, Medium, Low) based on the volume and sensitivity of the data they process and their criticality to the business.

Apply Proportional Due Diligence: Conduct due diligence that is appropriate to the vendor's risk tier. High-risk vendors should undergo the most stringent assessments.

Enforce Contractual Controls: Ensure a compliant DPA is in place for all vendors processing personal data. For high-risk vendors, negotiate enhanced clauses on liability, audit rights, and breach notification timelines.

Conduct Continuous Monitoring: Implement an ongoing monitoring program with a frequency and intensity that matches the vendor's risk tier. Leverage automated tools for real-time risk intelligence where possible.

Regularly Review and Offboard: Periodically review the vendor relationship and risk assessment. When a contract terminates, ensure a secure and documented data deletion or return process is executed.

8.3 Fostering a Culture of Data Protection Across the Supply Chain

Ultimately, true data protection cannot be achieved through contracts and audits alone. The most resilient organisations foster strong, transparent partnerships with their key vendors, treating data protection as a shared responsibility. This involves clear and regular communication about expectations, performance, and emerging threats. By moving from a purely adversarial, compliance-checking relationship to a collaborative partnership, organisations can build a more secure and trustworthy supply chain, which in itself becomes a competitive advantage.

8.4 Preparing for Future Regulatory Developments

The data protection landscape is not static. New laws, technologies, and regulatory interpretations continuously emerge. For instance, the UK's Data (Use and Access) Act is expected to bring changes to the UK's data protection framework, which will likely result in updated guidance from the ICO. Organisations must remain agile and proactive, with processes in place to monitor these developments and update their vendor risk management programs accordingly. By building a program on the foundational principles of accountability, risk management, and continuous improvement, organisations can ensure they are well-prepared to navigate the evolving challenges of managing vendor and third-party risk under the UK GDPR.

Conclusion

Managing vendor and third-party risks under GDPR requires a systematic, risk-based approach that encompasses the entire vendor lifecycle. Organizations must establish robust procedures for vendor assessment, implement appropriate contractual safeguards, maintain comprehensive documentation, and conduct ongoing monitoring of vendor compliance. The interconnected nature of modern business operations means that data protection risks extend beyond organizational boundaries, requiring vigilant oversight of third parties who process personal data on your behalf. By implementing the strategies outlined in this article, organizations can significantly reduce the compliance risks associated with vendor relationships while fostering a culture of accountability throughout their supply chain. Remember that vendor risk management is not a one-time exercise but a continuous process that must evolve as regulatory requirements, business relationships, and processing activities change. Investment in effective vendor management processes not only supports GDPR compliance but also builds trust with customers, partners, and regulators by demonstrating a commitment to responsible data handling practices regardless of where processing occurs.

Additional Resources

EU GDPR: A Comprehensive Guide - An in-depth exploration of GDPR requirements and implementation strategies.

Challenges and Best Practices for Cross-Border Data Transfers in Chat Systems Under GDPR - Expert guidance on managing international data transfers.

Privacy by Design: A Guide to Implementation Under GDPR - Strategies for embedding data protection into vendor processes from the outset.

Mastering Compliance Assessment of Data Processing - Advanced techniques for evaluating vendor compliance with GDPR requirements.

GDPR Compliance Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide - Systematic approaches to assessing and documenting compliance across vendor relationships.