Freedom of Expression and Data Protection under GDPR

Explore the delicate balance between freedom of expression and data protection under GDPR regulations, and discover practical approaches for businesses and individuals to navigate this complex intersection of fundamental rights.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the intricate relationship between freedom of expression and data protection within the European legal framework, particularly under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Both are recognized as fundamental human rights, yet their application often creates inherent tensions. The report highlights that neither right is absolute, and their legitimate limitations necessitate a continuous balancing act. Central to this reconciliation is GDPR Article 85, which mandates Member States to establish specific exemptions and derogations for processing personal data for journalistic, academic, artistic, and literary purposes.

The analysis delves into the foundational principles and scopes of both freedom of expression (under UDHR Article 19 and ECHR Article 10) and data protection (under GDPR Article 5 and its lawful bases). It examines how legitimate restrictions are applied, notably through the "triple test" of necessity and proportionality. Critical jurisprudential developments from the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) are explored, illustrating how courts navigate conflicts, particularly concerning the "right to be forgotten" versus journalistic archives and evolving liabilities for online content. The report also addresses the profound challenges of the digital age, including the significant influence of private actors on online expression, the complexities of content moderation, and the persistent need for greater regulatory harmonization across Member States. Ultimately, achieving a robust and democratic digital sphere requires ongoing vigilance, clear guidelines, and a commitment to upholding both these vital rights.

II. Introduction: The Dual Pillars of Fundamental Rights

Setting the Stage: The Importance of Both Rights

Freedom of expression stands as a cornerstone of open, democratic, and fair societies, empowering individuals to articulate their opinions, disseminate information, and advocate for accountability without fear of unlawful interference. This fundamental right is universally recognized, enshrined in Article 19 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and subsequently protected by a multitude of international and regional treaties. Its significance extends beyond mere speech, underpinning other essential human rights such as freedom of thought, conscience, religion, association, and peaceful assembly, allowing these rights to flourish within a vibrant public discourse.

In parallel, data protection, particularly as codified by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, serves as an equally fundamental right, designed to safeguard individuals' privacy and afford them control over their personal data. The GDPR’s core principles, meticulously outlined in Article 5, form the bedrock of this regulatory regime, dictating that all processing of personal data must be lawful, fair, and transparent. These principles are not merely guidelines but foundational tenets that directly and indirectly shape all other rules and obligations within the GDPR, making their observance the initial and crucial step for data controllers in fulfilling their legal duties.

The Inherent Tension and the Need for a Balanced Approach

The co-existence of freedom of expression and data protection, both recognized as fundamental human rights within the EU legal system, inevitably creates an inherent tension at their intersection. The exercise of one right can, at times, appear to impinge upon the other. For instance, the dissemination of information, a core aspect of freedom of expression, often involves the processing of personal data, which is subject to strict data protection rules.

It is crucial to acknowledge that neither freedom of expression nor data protection is an absolute right. Both are subject to legitimate limitations and carry inherent duties and responsibilities, particularly to respect the rights and freedoms of others. The challenge, therefore, lies not in choosing one over the other, but in meticulously finding a proportionate balance that allows both rights to be exercised effectively without unduly infringing upon the other. This complex task of reconciliation is explicitly mandated and addressed by GDPR Article 85, which serves as the primary legal mechanism for navigating this delicate balance.

III. Freedom of Expression: Principles, Scope, and Limitations

A. International and European Foundations

The right to freedom of expression is a universally recognized human right, broadly articulated in Article 19 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). This foundational principle has subsequently been reinforced and legally protected by numerous international and regional treaties. Within the European context, Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) provides robust protection, safeguarding an individual's right to hold opinions and express them freely without interference from public authorities. This encompasses the freedom to receive and impart information and ideas across borders, irrespective of the medium used. The scope of this right is expansive, covering diverse forms of expression, including public protests and demonstrations, published articles, books, leaflets, television and radio broadcasting, works of art, and increasingly, the internet and social media.

A significant aspect of Article 10 ECHR, as established in seminal cases such as Handyside v. United Kingdom, is that this right extends to ideas of all kinds, including those that may be deeply offensive, shocking, or disturbing. This broad interpretation underscores the importance of protecting challenging viewpoints in a democratic society, recognizing that a vibrant public discourse requires the free exchange of even unpopular or controversial ideas. While the principle of freedom of expression is universally acknowledged as a fundamental human right, its practical implementation and the precise boundaries of its limitations are not monolithic. Instead, they are highly contextual and subject to national interpretation within the broader international and regional legal frameworks. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) acknowledges this through the concept of the "margin of appreciation," which permits Member States a degree of flexibility in applying Article 10, recognizing varying historical, legal, political, and cultural differences across nations. This inherent flexibility, while allowing for cultural nuance and adaptation, simultaneously creates challenges for consistent application, particularly in cross-border digital environments.

B. Scope of Protection in the Digital Age

The advent of the digital era has profoundly expanded the avenues for exercising freedom of expression, with the internet and social media explicitly recognized as crucial spaces for communication and information exchange. Social media platforms, in particular, have transformed the landscape of political communication, enabling politicians to engage directly with the public and bypass traditional media gatekeepers. This direct interaction holds the potential to strengthen democratic values by fostering diverse voices and allowing for broader participation in public discourse.

However, this amplification of expression through digital channels is a dual-edged sword. The same platforms that facilitate democratic engagement also present significant challenges, including the proliferation of hate speech, the rapid dissemination of fake news, and the emergence of extremely polarized content. This necessitates a complex balancing act between upholding freedom of expression and preventing online and offline harms. The digital age has fundamentally expanded the reach and accessibility of freedom of expression, effectively democratizing information dissemination and public discourse. However, this amplification also exacerbates the challenges associated with content moderation, the rapid spread of harmful speech, and the increasing influence of private entities and state control over online spaces. This creates a complex and evolving battleground where the exercise of freedom of expression must constantly be balanced against the imperative to prevent harm and ensure responsible digital governance. The shift in power from traditional media gatekeepers to powerful online platforms introduces novel regulatory dilemmas.

C. Legitimate Restrictions and the "Triple Test"

Despite its fundamental importance, freedom of expression is not an absolute right and may be legitimately restricted under certain circumstances. Such restrictions are permissible when the expression violates the rights of others, advocates hatred, or incites discrimination or violence. However, any restriction imposed on freedom of expression must adhere to stringent conditions, commonly referred to as the "triple test," to ensure proportionality and legitimacy:

Prescribed by Law: The restriction must be established by law, meaning the legal basis for the limitation must be accessible to the public and its effects foreseeable.

Pursue a Legitimate Aim: The restriction must serve a legitimate public interest. Commonly recognized legitimate aims include the protection of national security, territorial integrity, or public safety; the prevention of disorder or crime; the protection of health or morals; the protection of the rights and reputations of other people; the prevention of the disclosure of information received in confidence; and the maintenance of the authority and impartiality of judges.

Necessary in a Democratic Society: The restriction must be proportionate to the aim pursued and no more than necessary to address the issue concerned. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) rigorously scrutinizes the rationale behind such restrictions, emphasizing that they must be convincingly established. The principle of proportionality is not a static legal benchmark but rather a dynamic, context-dependent assessment tool. It compels authorities to provide robust justification for

why a restriction is necessary, how it is precisely tailored to achieve its legitimate aim, and whether less intrusive alternatives could achieve the same objective. This necessitates that the balance between freedom of expression and its limitations is continuously recalibrated based on evolving societal norms, technological advancements, and the specific facts of each case, making it a living, evolving legal standard rather than a fixed boundary. Consequently, this principle places a significant burden of proof on any authority seeking to impose restrictions.

While hate speech may fall under the broad umbrella of freedom of expression, it can be legitimately limited to prevent incitement to violence or discrimination. However, legislating against hate speech is particularly challenging due to its highly contextual and subjective nature regarding content and victim.

D. The Role of Public Interest and Media Freedom

Freedom of expression holds particular importance for journalists and media professionals, who play a vital role in a democratic society by criticizing governments and public institutions without fear of prosecution. This critical function necessitates that media organizations are able to process personal data when producing journalistic content, especially when there is a demonstrable public interest in doing so. Data protection law explicitly acknowledges this necessity by incorporating specific rules designed to balance the right to privacy with the right to freedom of expression in this context.

The media's mission extends to providing the public with access to historical information maintained in their archives, a duty affirmed by the ECtHR. This ensures that the public can research past events and that the media continues to contribute to public opinion formation. The concept of "public interest" serves as a powerful and indispensable justification for the exercise of freedom of expression, particularly for the media, enabling the processing of otherwise protected personal data and ensuring access to historical information. However, it is not an unfettered concept; its application is subject to rigorous balancing tests against other fundamental rights, such as privacy, and is invalidated by demonstrable inaccuracies or when its exercise directly contributes to harm, such as through hate speech or incitement. This duality makes "public interest" a complex, two-sided concept: a crucial enabler of free speech and a necessary boundary for its responsible exercise.

IV. Data Protection under the GDPR: Core Principles and Individual Rights

A. The Seven Principles of Data Protection (Article 5 GDPR)

Article 5 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) establishes a set of key principles that form the bedrock of the entire data protection regime. These principles are foundational, directly and indirectly influencing all other rules and obligations within the legislation. For data controllers, compliance with these fundamental principles is the essential first step in fulfilling their duties under the GDPR. The GDPR's principles are not merely a list of rules; they represent the core philosophy and operational framework of data protection. Their foundational nature means that any attempt to reconcile data protection with other fundamental rights, particularly freedom of expression, must either strictly adhere to these principles or provide explicit and legally sound justifications for derogation. This implies that even when specific obligations are relaxed, for example for journalistic purposes, the underlying spirit of these principles, such as fairness, security, and proportionality, often remains relevant, guiding how data processing should still be conducted responsibly and ethically. The very provision for derogation underscores their central and default application.

These principles include:

Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency: Any processing of personal data must be lawful, fair, and conducted transparently. Individuals must be clearly informed about the collection, use, and extent of processing of their personal data, using easily accessible and understandable language.

Purpose Limitation: Personal data should be collected only for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner incompatible with those initial purposes. However, further processing for archiving, scientific, historical research, or statistical purposes in the public interest is generally considered compatible.

Data Minimisation: The processing of personal data must be adequate, relevant, and strictly limited to what is necessary for the purposes for which it is processed. This implies that data should only be processed if the purpose could not reasonably be fulfilled by other means.

Accuracy: Data controllers must ensure that personal data is accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date. They must take every reasonable step to ensure that inaccurate data, considering the purposes for which it is processed, is erased or rectified without delay.

Storage Limitation: Personal data should only be kept in a form that permits identification of data subjects for as long as is necessary for the purposes for which it is processed. Controllers are required to establish time limits for erasure or periodic review to ensure data is not stored longer than necessary.

Integrity and Confidentiality: Personal data must be processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security and confidentiality. This includes protection against unauthorized or unlawful access, use, accidental loss, destruction, or damage, through the implementation of appropriate technical or organizational measures.

Accountability: The data controller bears the responsibility for, and must be able to demonstrate, compliance with all the aforementioned principles. This requires controllers to take responsibility for their processing activities and maintain appropriate records and measures to prove their compliance.

B. Lawful Bases for Processing Personal Data

The GDPR mandates that all processing of personal data must be grounded in a lawful basis to ensure its legitimacy. There are six distinct legal bases that organizations can rely upon for processing personal data :

Consent: This is a common basis, requiring individuals to provide clear, explicit, and freely given consent for their data to be processed. Data subjects retain the right to withdraw their consent at any time.

Contractual Obligation: Processing personal data is justified if it is necessary for the performance of a contract with the data subject or to take steps at their request prior to entering into a contract.

Legal Obligation: This basis applies when processing personal data is a requirement to comply with a legal obligation imposed on the data controller by Union or Member State law.

Vital Interests: Processing personal data can be justified if it is necessary to protect the vital interests of the data subject or another natural person, particularly in life-threatening situations.

Public Task: This basis applies when processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the data controller.

Legitimate Interests: Processing personal data may be justified if it is necessary for the legitimate interests pursued by the data controller or a third party. However, this basis is qualified by a crucial caveat: these interests must not be overridden by the fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject, especially where the data subject is a child. While the "Legitimate Interests" basis offers considerable flexibility for data controllers, its application is inherently susceptible to legal challenge and conflict when it directly impinges upon other fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression or the right to privacy. It necessitates a careful, documented, and demonstrable balancing exercise, often making it a less straightforward and more scrutinized basis for processing compared to, for example, explicit consent or a clear legal obligation. Its broad nature means it can be a 'catch-all' but also the most vulnerable to being overridden by individual rights.

C. Data Subject Rights

The GDPR empowers individuals with several fundamental rights concerning their personal data, ensuring they have significant control over how their information is processed :

Right to be Informed: Individuals have the right to be informed about the collection and use of their personal data, including the purposes of processing, the legal basis, retention periods, and who the data will be shared with.

Right of Access: Every individual is entitled to obtain confirmation as to whether personal data concerning them is being processed, and, where that is the case, access to the personal data and certain information about its processing.

Right to Rectification: If personal information is inaccurate or incomplete, individuals have the right to request its correction or completion without undue delay.

Right to Erasure ("Right to be Forgotten"): This right allows individuals to request the deletion or removal of their personal data where there is no compelling reason for its continued processing, such as when the data is no longer necessary for the purposes for which it was collected.

Right to Restriction of Processing: Individuals have the right to request the restriction or suppression of their personal data in certain circumstances, meaning organizations can store the data but not use it.

Right to Data Portability: This right allows individuals to obtain and reuse their personal data for their own purposes across different services, enabling them to move, copy, or transfer personal data easily from one IT environment to another in a safe and secure way.

Right to Object: Individuals have the right to object to the processing of their personal data in certain circumstances, including processing for direct marketing purposes.

Rights in relation to Automated Processing: Individuals have the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning them or similarly significantly affects them, unless certain conditions are met.

Data controllers are generally required to respond to data subject requests within one month of receipt. This period can be extended by two further months for complex or numerous requests, provided the data subject is informed of the extension and the reasons for the delay within the initial one-month period. Importantly, organizations cannot charge a fee for handling these requests, unless they are manifestly unfounded or excessive.

The "right to be forgotten" stands out as the most direct and frequently contentious point of friction between data protection and freedom of expression. While intended to empower individuals by allowing them to control their digital footprint, its exercise often directly challenges the public's right to information and the media's essential role in maintaining historical archives. Case law from both the ECtHR and CJEU consistently demonstrates that this right is not absolute and is subject to a rigorous proportionality test that heavily weighs the public interest, especially when the information is accurate and pertains to public figures or matters of general societal interest. This ongoing tension creates a continuous legal and ethical dilemma for online platforms, search engines, and media organizations.

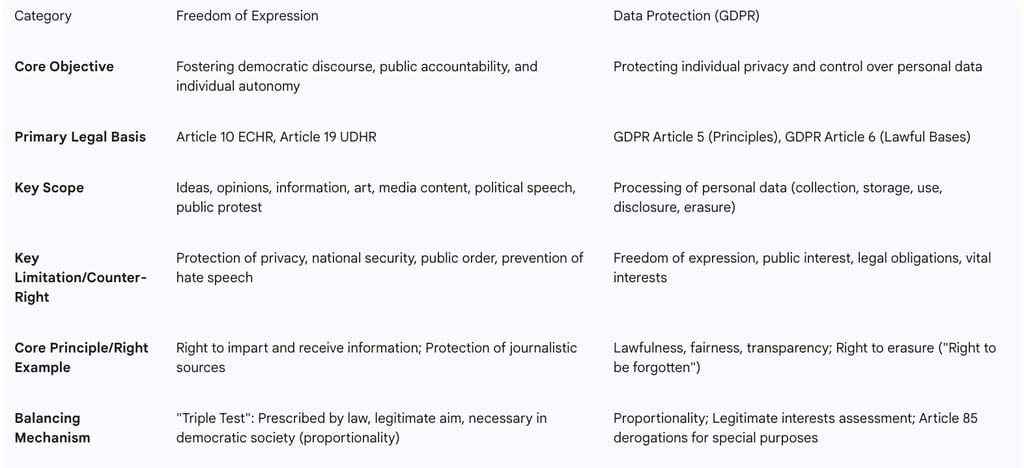

Table 1: Comparison of Freedom of Expression and Data Protection Principles

V. Reconciling Rights: GDPR Article 85 and the "Special Purposes" Exemption

A. Article 85 GDPR: The Mandate for Reconciliation

GDPR Article 85 serves as a pivotal provision, explicitly mandating that Member States shall, by law, reconcile the fundamental right to the protection of personal data with the equally fundamental right to freedom of expression and information. This reconciliation is specifically extended to include processing personal data for journalistic purposes, as well as for purposes of academic, artistic, or literary expression. Recital 153 further reinforces the importance of this delicate balance, acknowledging that such processing activities may necessitate specific rules to ensure that both fundamental rights are upheld. To fully account for the importance of freedom of expression in every democratic society, the notion of "journalism" within this context should be interpreted broadly, encompassing a wide range of activities that contribute to public discourse.

While Article 85 aims to establish a unified framework for balancing these fundamental rights across the EU, its delegation of specific implementation details to individual Member States inadvertently introduces a degree of fragmentation. Evidence indicates that Member States have adopted varying standards for journalistic exemptions, which are often inconsistent with broader EU law. This means that despite the overarching goal of harmonization, the practical application of these provisions can vary significantly across the Union, potentially undermining the GDPR's objective of legal certainty. This inconsistency complicates compliance for data controllers operating across multiple jurisdictions and can impede seamless cross-border data flows, highlighting a persistent tension between unified EU regulation and national legislative flexibility. Where such exemptions or derogations differ, the law of the Member State to which the controller is subject should apply.

B. Exemptions and Derogations for Journalistic, Academic, Artistic, and Literary Purposes

For processing activities carried out for these "special purposes"—journalistic, academic, artistic, or literary expression—Member States are obligated to provide exemptions or derogations from specific chapters of the GDPR. These exemptions are crucial to ensure that the rigorous requirements of data protection do not unduly hinder the exercise of freedom of expression in these vital fields. The chapters from which derogations can be made include:

Chapter II (Principles relating to processing of personal data)

Chapter III (Rights of the data subject)

Chapter IV (Controller and processor obligations)

Chapter V (Transfers of personal data to third countries or international organizations)

The UK's Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) guidance on the "Journalism, academia, art and literature" exemption provides practical insights into its application. This exemption can relieve organizations from obligations concerning most of the GDPR principles (with the notable exceptions of the security and accountability principles), lawful bases for processing, conditions for consent, children’s consent, conditions for processing special categories of personal data and criminal convictions, processing not requiring identification, the right to be informed, most individual rights (except those related to automated individual decision-making), notification of personal data breaches to individuals, consultation with the ICO for high-risk processing, international transfers of personal data, and cooperation and consistency between supervisory authorities.

However, this exemption is not a blanket immunity. It applies only to the extent that compliance with the GDPR provisions would be genuinely incompatible with the special purposes. This implies that mere inconvenience is insufficient; there must be a reasonable belief that adherence to the GDPR would prejudice or seriously impair the ability to carry out the special purpose. Furthermore, the processing must be carried out with a view to the publication of journalistic, academic, artistic, or literary material, and the controller must reasonably believe that the publication of this material would be in the public interest. This reveals that the "special purposes" exemption is a carefully calibrated mechanism designed to provide necessary operational flexibility for media and creative industries, rather than an unconditional shield. It is always contingent on a demonstrable public interest and a careful weighing of potential harm to individuals. Consequently, organizations cannot merely assert their activities as "journalistic" to bypass GDPR; they must genuinely serve a public interest, which implies an ongoing responsibility and potential for scrutiny by supervisory authorities. The "incompatibility" clause further suggests that the exemption is granted out of practical necessity, not mere convenience.

C. The Public Interest Test in Practice

When assessing whether publication falls within the public interest, data controllers, particularly media organizations, are expected to consider relevant industry guidelines and codes of practice. In the UK, this includes having regard to the BBC Editorial Guidelines, the Ofcom Broadcasting Code, and the Editors’ Code of Practice. These established codes provide sector-specific interpretations and best practices for balancing freedom of expression with data protection.

The ICO expects organizations to be able to explain and document their reasons for relying on the special purposes exemption in each specific case, demonstrating how and by whom the public interest assessment was conducted at the time. While the ICO does not necessarily have to agree with the organization's view, it must be satisfied that the organization held a reasonable belief that the publication was in the public interest. This highlights a significant reliance on established industry self-regulation and ethical guidelines as a practical benchmark for determining "public interest" and ensuring responsible conduct within the media sector. While GDPR provides the overarching legal framework, these professional codes offer sector-specific interpretations and best practices for balancing freedom of expression with data protection. This suggests a hybrid regulatory model where legal mandates are supplemented and informed by professional standards, influencing how the exemptions are applied and justified in real-world scenarios.

VI. Case Law and Jurisprudential Developments: Balancing Act in Practice

The complex interplay between freedom of expression and data protection has been a recurring theme in the jurisprudence of both the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). These courts have played a crucial role in interpreting and applying these fundamental rights in various real-world scenarios, establishing precedents that guide their reconciliation.

A. The Right to be Forgotten vs. Freedom of Information

The "right to be forgotten," or the right to erasure, frequently clashes with the public's right to access information, particularly concerning journalistic archives.

The ECtHR addressed this conflict in ML and WW v. Germany (2018). This case involved two individuals convicted of murder who sought the erasure of their names from old online news articles following their release from prison. The Court ruled that the public's legitimate right of access to electronic press archives, protected by freedom of expression and information, could indeed trump the right to request the erasure of personal data on prior convictions. The ECtHR emphasized the media's vital role in shaping public opinion, which includes the duty to provide access to historical information maintained in their archives. While acknowledging that anonymization might be a less intrusive measure, the Court deemed that providing names and individualizing information was crucial for journalistic credibility. The decision considered factors such as the objective and factual nature of the news articles, the applicants' prior engagement with the media, the high-profile nature of the murder, and the limited dissemination of the articles (requiring active searching). This judgment largely affirmed the prevalence of freedom of expression for accurate journalistic archives, even over a significant passage of time, noting that anonymization compromises journalistic credibility.

In contrast, the CJEU in C-460/20 provided a critical nuance to this balance, particularly concerning inaccurate information. The Court reiterated that the right to protection of personal data is not absolute and must be balanced against other fundamental rights, including freedom of information, based on the principle of proportionality. The GDPR explicitly states that the right to erasure is excluded if processing is necessary for exercising the right of information. However, the CJEU crucially determined that the right to freedom of expression and information cannot be taken into account where even a part of the information found in the referenced content is proven to be manifestly inaccurate. This creates a clear and significant legal distinction: while accurate historical journalistic content generally enjoys robust protection under freedom of expression, demonstrably false or misleading information loses this protection entirely, tipping the balance decisively towards the data subject's right to erasure. The burden falls on the person requesting removal to establish this manifest inaccuracy with relevant and sufficient evidence. Once such evidence is provided, the search engine operator is obligated to comply with the removal request. The Court also applied this balancing act to the display of thumbnail photos, requiring an assessment of their informational value against the individual's right to privacy. This ruling establishes a high, but clear, threshold for individuals to challenge online information, underscoring the paramount importance of factual accuracy in public discourse and implicitly placing a de facto responsibility on search engines to assess credible evidence of inaccuracy.

B. Protection of Journalistic Sources and Media Injunctions

The protection of journalistic sources is a cornerstone of press freedom, recognized as essential for the media's ability to inform the public and hold power accountable.

In Nagla v. Latvia (2013), the ECtHR found a violation of Article 10 when police searched a broadcast journalist's home and seized her data storage devices after she aired information leaked from a state database. The Court emphasized that the right of journalists not to disclose their sources is an intrinsic part of the right to information and cannot be considered a mere privilege dependent on the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the sources themselves. The ECtHR places an exceptionally high and fundamental value on the protection of journalistic sources, recognizing it as absolutely essential for the media's ability to effectively inform the public, investigate matters of public interest, and hold powerful entities accountable. This robust stance implies that state interference, even under the guise of legitimate investigations, is severely limited when it risks compromising confidential sources, thereby reinforcing the media's critical watchdog role as an indispensable pillar of a democratic society.

The landmark case of Sunday Times v. UK (no. 1) (1979), which was the first ECtHR judgment concerning freedom of expression via the press, also resulted in a finding of an Article 10 violation. This case concerned an injunction served on the Sunday Times that restrained the publication of news about pending civil proceedings related to thalidomide deformities. The Court found that while the initial injunction might have been justifiable, its continuation after the information was no longer confidential infringed on the newspaper's right to freedom of expression.

C. Online Content Liability and Social Media

The rise of online platforms and social media has introduced complex questions regarding liability for user-generated content and the extent of content moderation obligations.

In Delfi AS v. Estonia, the ECtHR found a large online news portal liable for defamatory comments posted by anonymous users on its platform. The Court held that the company's automatic filtering and notice-and-take-down system were insufficient given its commercial interest and its ability to foresee defamatory comments. States, the Court noted, could impose liability on online news portals to remove clearly unlawful comments without delay. However, this active monitoring obligation was specifically limited to large, professionally managed online news portals and did not extend to discussion forums, social media platforms, or personal blogs where users freely disseminate ideas without provider influence or significant financial motivation.

The Sanchez v. France case further complicated the landscape, with the ECtHR establishing an active monitoring obligation for an elected official who failed to remove unlawful comments under his public Facebook posts during an election campaign. The Court cited the special duties and responsibilities of elected officials, blurring the lines of liability for public figures on social media.

The principle was reiterated in Zöchling v. Austria, where the ECtHR confirmed that even smaller online news portals with commercial interests have a responsibility to monitor and promptly remove clearly unlawful content, even without prior notification from victims. This suggests a minimum degree of subsequent moderation or automatic filtering is expected.

European jurisprudence is demonstrating a clear trend towards a more nuanced, and in many instances, stricter, liability regime for online content. The traditional "publisher vs. platform" distinction is becoming increasingly complex, with a discernible shift towards imposing greater responsibility on entities (including individuals in public roles) who derive commercial benefit from or exert significant influence over public discourse online. This evolving legal landscape creates a challenging environment for platforms and individuals, pushing them towards more proactive content moderation. However, it also raises significant concerns about potential chilling effects on legitimate freedom of expression and the practical feasibility of universal content monitoring, especially given the stark divergence in regulatory philosophies between the EU and the US. The US framework, notably Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA), largely protects online platforms from liability for user-generated content, while the EU's Digital Services Act (DSA) imposes more severe, proactive obligations on very large online platforms (VLOPs), mandating transparency in content moderation, risk assessments, and user redress mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Jurisprudential Developments: Balancing FoE and Data Protection

VII. Practical Challenges and Future Outlook in the Digital Age

The digital age, while expanding the reach of expression, has introduced profound challenges to the delicate balance between freedom of expression and data protection. These challenges stem from a complex interplay of technological advancements, the increasing influence of private actors, and the evolving regulatory landscape.

A. Impact of Private Actors and Technology

The pervasive nature of technology means that a broad array of private actors, beyond just the large transnational companies like search engines and social media platforms, significantly impact freedom of expression in the digital age. Less scrutinized entities also play crucial roles. For instance, Internet Exchange Points (IXPs), which are physical infrastructures where Internet Service Providers (ISPs) exchange traffic, can become centralized targets for internet censorship and surveillance. This can occur through the installation of filtering hardware or by injecting bad DNS responses, redirecting users away from censored content. Similarly, Domain Registries and Registrars, responsible for managing and selling domain names, are vulnerable to threats from law enforcement, often leading to the removal or unavailability of domains. This frequently happens under the guise of intellectual property rights, security, or terrorism concerns, but can also restrict permissible speech such as political commentary or parody. Even Standard Setting Bodies like the IETF, ITU, and W3C, which develop voluntary standards and protocols for the internet, can inadvertently influence online freedom of expression through their technical decisions. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a multi-stakeholder body managing internet domain names and addresses, also directly impacts human rights, including freedom of expression and privacy, with concerns raised about public access to personal information in the WHOIS database potentially chilling expression for sensitive registrations.

States often contribute to the problem by imposing legal and regulatory frameworks that are incompatible with international freedom of expression laws, thereby hindering companies from respecting human rights online. Examples include compelling companies to hand over personal data without due process, requiring "kill switches" to shut down internet services, or mandating identity verification systems that negatively impact the privacy and expression of whistleblowers and dissidents. Furthermore, ill-designed laws can be abused by private actors themselves to force intermediaries to violate freedom of expression. For instance, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in the US is frequently used to request the removal of content that would otherwise be permissible under international human rights norms, under the guise of protecting intellectual property rights.

Beyond legal obligations, the private sector often takes voluntary actions through their terms of service and community guidelines that negatively impact online freedom of expression. These actions can stem from pressure to remove content or close accounts, or from business models that inadvertently threaten human rights, such as zero-rated practices. Examples include Facebook's content flagging policies, nudity guidelines, or real-name policies, which have been criticized for silencing unpopular views, violating cultural expression, or infringing on the rights of those relying on anonymity. Online harassment, hate speech, and stalking also contribute to a chilling effect, leading individuals, particularly women, to self-censor or withdraw from online spaces. The digital age has fundamentally shifted the locus of control over freedom of expression, moving beyond traditional state-centric censorship to a complex, multi-stakeholder ecosystem where private entities exert immense, often unscrutinized, power. This "privatization of censorship" occurs through technical infrastructure, content moderation policies, and business models, frequently without the robust due process, transparency, or accountability safeguards typically associated with state actions. This dynamic creates a de facto regulatory vacuum or a fragmented patchwork of inconsistent rules, making it increasingly challenging to hold these powerful private actors accountable and effectively protect individual rights. The absence of globally harmonized standards exacerbates this problem, leading to inconsistent application of freedom of expression principles worldwide.

B. Political Communication and Social Media

Social media has profoundly transformed political communication, enabling politicians to engage directly with the public and bypass traditional media gatekeepers. While this expansion can strengthen democratic values by allowing diverse voices to contribute to public discourse, it simultaneously presents significant challenges, including the proliferation of hate speech, fake news, and extremely polarized content. Balancing freedom of expression with the prevention of online and offline harms necessitates careful regulatory approaches.

The speech of public officials is subject to higher scrutiny due to their influence and responsibilities, carrying an elevated duty not to share inflammatory or misleading content. However, imposing excessive restrictions on their speech could paradoxically undermine democratic processes. The governance of online political communication presents a profound democratic dilemma. While platforms have democratized public discourse, their immense power over content moderation, often influenced by commercial interests or national pressures, can inadvertently lead to censorship or the unchecked amplification of harmful narratives.

The differing regulatory philosophies between the US and the EU highlight this challenge. In the US, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA) largely protects online platforms from liability for user-generated content, allowing them broad discretion in content moderation. In contrast, the EU's Digital Services Act (DSA) imposes more severe and proactive obligations on very large online platforms (VLOPs), mandating transparency in content moderation, requiring risk assessments and mitigation, and providing users with mechanisms to challenge content removal decisions. This divergence creates an environment where platforms operate under conflicting legal regimes, leading to inconsistent application of freedom of expression principles and a potential chilling effect on legitimate speech, particularly for public figures whose online presence is crucial for democratic engagement. This necessitates an urgent global dialogue on developing transparent, accountable, and rights-respecting governance models for digital platforms.

C. Regulatory Landscape and Harmonisation

Despite the GDPR's explicit objective to ensure consistent application across the European Union, particularly through the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) , Member States continue to exhibit varying standards for journalistic exemptions under Article 85, which are often inconsistent with broader EU law. This disharmonization undermines the promised legal certainty of the GDPR, complicating compliance for data controllers operating across multiple jurisdictions and impeding seamless cross-border data flows within the EU. The EDPB attempts to mitigate these inconsistencies by issuing general guidance, guidelines, and recommendations to clarify the law and promote a common understanding of EU data protection laws.

Despite the GDPR's ambitious goal of creating a harmonized data protection landscape across the European Union, the reconciliation of freedom of expression and data protection remains a patchwork, largely due to diverse interpretations of Article 85 by Member States. This internal fragmentation creates legal uncertainty and operational challenges within the EU. However, this internal struggle contrasts with the EU's external influence, where its assertive regulatory stance, often referred to as the "Brussels Effect," is shaping global norms and practices. This suggests that while the EU can effectively project its standards internationally, achieving full internal consistency on this complex intersection of fundamental rights remains an ongoing and significant challenge.

D. Media Concentration and its Implications for Freedom of Expression

Beyond legal frameworks and platform-specific policies, the underlying economic structure of the media landscape itself poses a significant, often overlooked, threat to freedom of expression. There is an increasing global trend of media industry consolidation and cross-ownership between electronic media production companies, broadband infrastructure, and telecommunication operators. These trends blur traditional industry boundaries as mobile and fixed network operators merge, satellite and cable TV broadcasters combine and become internet access providers, and traditional voice operators provide broadcast TV and radio over broadband.

These developments raise several concerns for freedom of expression. Firstly, they can lead to a diminished role for public service broadcasting in the new electronic media environment, making it harder for public service information to reach wider audiences, particularly "cord cutters". Secondly, increasing stratification and inequality in service provision can emerge, leading to isolation and making it difficult to reach all segments of the public uniformly. Lastly, there is a notable lack of national net neutrality policy frameworks that adequately cover cross-ownership and intricate business relationships between infrastructure providers and content producers. This economic concentration can subtly, yet powerfully, shape public discourse and limit the effective exercise of freedom of expression, even in the absence of overt censorship, by controlling access to information and platforms, thereby undermining the democratic ideal of a marketplace of ideas.

VIII. Conclusion and Recommendations

Summarizing the Delicate Balance Required

The analysis underscores that both freedom of expression and data protection are indispensable fundamental rights within the European legal order, neither of which is absolute. Their inherent tension necessitates a continuous and nuanced process of reconciliation. GDPR Article 85 stands as the primary legal mechanism designed to facilitate this balance, particularly by providing specific exemptions and derogations for processing personal data for journalistic, academic, artistic, and literary purposes.

Jurisprudence from the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Union has been instrumental in interpreting and applying these rights in complex, real-world scenarios. This is particularly evident in cases concerning the "right to be forgotten" versus journalistic archives, where the accuracy of information proves paramount, and in the evolving liabilities for online content, which increasingly place responsibility on platforms and public figures. The digital age introduces profound challenges, as the influence of private actors on online expression, the complexities of content moderation, and the persistent need for greater regulatory harmonization across Member States continue to shape this dynamic landscape.

Recommendations

To foster a robust and rights-respecting digital environment, the following recommendations are put forth:

For Policymakers and Legislators:

Harmonize Article 85 Implementation: Greater harmonization in the implementation of GDPR Article 85 across Member States is crucial to ensure legal certainty and consistency. This could be achieved through more detailed guidelines from the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) or through further EU-level directives that provide clearer boundaries for national derogations.

Refine "Public Interest" Criteria: Develop clear, consistent, and transparent criteria for assessing "public interest" in the digital context. These criteria should meticulously balance the public's right to information with individual data protection rights, while also preventing the misuse of public interest claims to justify unwarranted data processing or infringements on privacy.

Strengthen Oversight of Private Actors: Establish robust oversight mechanisms for powerful private actors, including social media platforms, internet service providers, and foundational infrastructure providers. These mechanisms should ensure that their policies and practices, particularly concerning content moderation, align with human rights standards, offering due process, transparency, and effective redress mechanisms for individuals.

Address Media Concentration: Implement policies and regulatory frameworks that address concerns related to media concentration and cross-ownership. This is vital to safeguard media pluralism, ensure a diversity of voices, and guarantee equitable access to information for all segments of the public, thereby preventing economic power from unduly limiting freedom of expression.

For Data Controllers (especially media organizations and those involved in "special purposes" processing):

Proactive Data Protection: Proactively implement data protection by design and by default in all processing activities, even when exemptions under Article 85 apply. This ensures that security and accountability principles are upheld, fostering trust and minimizing risks.

Enhanced Transparency: Maintain full transparency with data subjects regarding data processing activities, even if certain information rights are derogated from under specific exemptions. Clear privacy notices and accessible information about data handling practices remain essential.

Rigorous Legitimate Interest Assessments: Conduct thorough and well-documented legitimate interest assessments when relying on this lawful basis. This requires carefully balancing organizational interests with data subjects' fundamental rights and freedoms, demonstrating proportionality and necessity.

Streamlined Data Subject Rights Processes: Establish clear, accessible, and timely processes for handling data subject rights requests, particularly the "right to be forgotten." This includes robust procedures for verifying and addressing claims of manifest inaccuracy in published information, ensuring prompt rectification or erasure where warranted.

Adherence to Ethical Standards: Adhere to high journalistic, academic, artistic, and ethical standards in all processing activities. This includes justifying the public interest in all content that involves personal data, demonstrating a commitment to responsible information dissemination.

For Individuals:

Empowerment through Awareness: Be aware of their data protection rights under the GDPR and understand how to effectively exercise them. This knowledge is crucial for asserting control over their personal information in the digital sphere.

Responsible Expression: Understand the legitimate limitations on freedom of expression and the responsibilities that accompany it, particularly regarding hate speech, incitement to violence, and the rights and reputations of others.

Critical Digital Literacy: Cultivate critical digital literacy skills to discern accurate information from misinformation and disinformation. This empowers individuals to engage responsibly in online discourse and make informed decisions about the content they consume and share.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are freedom of expression and data protection, and why are they considered fundamental rights in the EU?

Freedom of expression, enshrined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), is a cornerstone of democratic societies. It empowers individuals to articulate opinions, disseminate information, and hold authorities accountable without unlawful interference. It underpins other vital human rights, fostering a vibrant public discourse.

Data protection, particularly as codified by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, is an equally fundamental right. Its core purpose, outlined in GDPR Article 5, is to safeguard individual privacy and provide control over personal data. This includes ensuring data processing is lawful, fair, and transparent, with individuals informed about how their data is collected and used. Both rights are recognised as fundamental human rights within the EU legal system because they are considered essential for individual autonomy, democratic participation, and the functioning of a fair society.

2. What is the inherent tension between freedom of expression and data protection, and how does GDPR Article 85 aim to reconcile it?

The co-existence of freedom of expression and data protection, both fundamental rights, creates an inherent tension because the exercise of one can impinge upon the other. For instance, disseminating information (freedom of expression) often involves processing personal data, which is subject to strict data protection rules. Neither right is absolute; both are subject to legitimate limitations and responsibilities.

GDPR Article 85 serves as the primary legal mechanism to reconcile this delicate balance. It explicitly mandates Member States to establish specific exemptions and derogations for processing personal data for journalistic, academic, artistic, and literary purposes. This aims to prevent data protection rules from unduly hindering the exercise of freedom of expression in these vital fields, acknowledging their importance to a democratic society.

3. What are the key principles of data protection under GDPR Article 5?

GDPR Article 5 establishes seven foundational principles that underpin the entire data protection regime:

Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency: Personal data processing must be legal, fair, and transparent, with individuals clearly informed about data collection and use.

Purpose Limitation: Data should be collected only for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner incompatible with those initial purposes (though archiving, scientific, historical research, or statistical purposes in the public interest are generally compatible).

Data Minimisation: Processing must be adequate, relevant, and strictly limited to what is necessary for the stated purposes.

Accuracy: Data controllers must ensure personal data is accurate, kept up to date, and promptly rectified or erased if inaccurate.

Storage Limitation: Data should only be kept in a form that permits identification of data subjects for as long as necessary for the purposes for which it is processed.

Integrity and Confidentiality: Data must be processed securely, protected against unauthorised access, loss, destruction, or damage, through appropriate technical and organisational measures.

Accountability: The data controller is responsible for and must be able to demonstrate compliance with all the aforementioned principles.

4. What is the "triple test" for legitimately restricting freedom of expression?

Despite its fundamental importance, freedom of expression is not absolute and can be legitimately restricted under certain circumstances, for example, when it violates the rights of others or incites hatred. Any such restriction must adhere to the "triple test" to ensure proportionality and legitimacy:

Prescribed by Law: The restriction must have a clear legal basis, accessible to the public and its effects foreseeable.

Pursue a Legitimate Aim: The restriction must serve a legitimate public interest, such as protecting national security, public safety, health, morals, or the rights and reputations of others.

Necessary in a Democratic Society: The restriction must be proportionate to the aim pursued and no more than necessary to address the issue. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) rigorously scrutinises this, requiring robust justification for why a restriction is essential and whether less intrusive alternatives exist. This means the balance is continuously recalibrated based on evolving societal norms and specific case facts.

5. How does the "right to be forgotten" conflict with freedom of expression, and how have courts balanced these rights?

The "right to be forgotten" (right to erasure), which allows individuals to request the deletion of their personal data, frequently clashes with the public's right to access information, particularly concerning journalistic archives.

The ECtHR, in cases like ML and WW v. Germany (2018), has largely affirmed that freedom of expression can trump the right to erasure for accurate journalistic content in the public interest, even for old archives. The Court emphasised the media's vital role in providing access to historical information.

However, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in C-460/20 (2020) introduced a crucial nuance: if any part of the information found in the referenced content is proven to be manifestly inaccurate, then freedom of expression cannot justify its processing, and de-referencing (removal from search results) is required. This places the burden on the individual requesting removal to prove inaccuracy, but if proven, the balance tips decisively towards the data subject's right to erasure.

6. What is the significance of protecting journalistic sources, and what have court rulings indicated about this?

The protection of journalistic sources is a cornerstone of press freedom and is considered absolutely essential for the media's ability to inform the public and hold power accountable.

In Nagla v. Latvia (2013), the ECtHR found a violation of Article 10 when police searched a journalist's home after she aired leaked information. The Court emphasised that the right of journalists not to disclose their sources is an intrinsic part of the right to information and cannot be considered a mere privilege. This robust stance by the ECtHR highlights the exceptionally high value placed on source protection, reinforcing the media's critical watchdog role as an indispensable pillar of a democratic society. It implies that state interference is severely limited when it risks compromising confidential sources.

7. What challenges does the digital age pose to freedom of expression and data protection, particularly regarding private actors and content moderation?

The digital age profoundly expands avenues for expression but introduces significant challenges. The locus of control over freedom of expression has shifted, with private actors like social media platforms, search engines, and even internet infrastructure providers (e.g., IXPs, Domain Registries) exerting immense, often unscrutinised, power. This "privatisation of censorship" occurs through technical infrastructure, content moderation policies, and business models, often without the robust due process or transparency associated with state actions.

Cases like Delfi AS v. Estonia and Zöchling v. Austria show a trend towards increasing liability for commercial online news portals for user-generated defamatory content, requiring them to implement sufficient moderation. Sanchez v. France further blurred lines by imposing an "active monitoring obligation" on elected officials for comments on their public social media pages. This evolving legal landscape creates a challenging environment for platforms and individuals, pushing towards more proactive content moderation, but also raising concerns about chilling effects on legitimate speech and the practical feasibility of universal monitoring, especially given the divergence in regulatory philosophies between the EU (e.g., DSA) and the US (e.g., Section 230 CDA).

8. What are the recommendations for policymakers and data controllers to better balance these rights in the digital age?

To foster a robust and rights-respecting digital environment, the following recommendations are crucial:

For Policymakers and Legislators:

Harmonise Article 85 Implementation: Provide clearer guidelines or EU-level directives to ensure consistent application of GDPR Article 85 journalistic exemptions across Member States, reducing fragmentation and legal uncertainty.

Refine "Public Interest" Criteria: Develop clear, consistent, and transparent criteria for assessing "public interest" in the digital context, meticulously balancing public information rights with individual data protection.

Strengthen Oversight of Private Actors: Establish robust oversight mechanisms for powerful private actors (platforms, ISPs) to ensure their content moderation policies align with human rights standards, offering due process and redress.

Address Media Concentration: Implement policies to safeguard media pluralism and diversity of voices, preventing economic concentration from unduly limiting freedom of expression.

For Data Controllers (especially media organisations):

Proactive Data Protection: Implement data protection by design and by default, even when Article 85 exemptions apply, upholding security and accountability principles.

Enhanced Transparency: Maintain full transparency with data subjects regarding processing activities, providing clear privacy notices.

Rigorous Legitimate Interest Assessments: Conduct thorough and documented assessments when relying on legitimate interests, carefully balancing organisational interests with data subjects' rights.

Streamlined Data Subject Rights Processes: Establish clear, accessible, and timely processes for handling data subject requests, particularly the "right to be forgotten," including robust procedures for verifying and addressing claims of manifest inaccuracy.

Adherence to Ethical Standards: Adhere to high journalistic, academic, artistic, and ethical standards, justifying the public interest in all content involving personal data.

Additional Resources

EU GDPR: A Comprehensive Guide - A detailed overview of GDPR principles and requirements

Balancing Data Protection and Innovation Under GDPR - Further exploration of balancing competing interests within GDPR

The Right to Digital Privacy: Ensuring Data Protection in the Digital Age - In-depth analysis of privacy rights in online contexts

GDPR Enforcement Trends and Notable Cases - Analysis of how regulators are addressing complex balancing questions in practice

Addressing Ethical Considerations in AI Deployment Under GDPR - Exploring the ethical dimensions of expression, data protection, and technology