Privacy Policies and Transparency under GDPR

Discover how GDPR transformed privacy policies from legal jargon to transparent communication tools. Learn key transparency requirements, implementation best practices, and how to turn compliance into competitive advantage.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of data privacy, elevating transparency from a peripheral compliance item to a central, non-negotiable pillar of lawful data processing. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the principle of transparency as articulated within the GDPR, its practical application through privacy policies and notices, and the significant consequences of non-compliance. It is intended to serve as a definitive guide for Data Protection Officers, legal counsel, and compliance professionals navigating their obligations under this comprehensive legal framework.

The analysis begins by deconstructing the foundational principles of Article 5, which inextricably links transparency with the concepts of lawfulness and fairness. It demonstrates that transparent processing is not merely a disclosure requirement but the essential mechanism through which fairness is achieved and lawfulness is validated. The report then provides a granular exegesis of the key legal articles governing the provision of information—Article 12 (Modalities), Article 13 (Direct Data Collection), and Article 14 (Indirect Data Collection)—translating these legal requirements into a practical blueprint for drafting and implementing effective privacy notices.

Moving from theory to practice, this report outlines the anatomy of a GDPR-compliant privacy policy and explores modern, user-centric communication strategies such as layered notices and just-in-time alerts, which are endorsed by supervisory authorities. It repositions the privacy notice not as a legal liability to be minimized, but as a critical component of user experience and a tool for building consumer trust.

The tangible risks of failing to meet these obligations are examined through an analysis of the enforcement landscape. A review of landmark fines levied by supervisory authorities reveals a clear pattern: the most severe penalties are reserved for systemic transparency failures that obscure the legal basis for processing and undermine the data subject's ability to exercise control over their personal data.

Furthermore, the report confronts the emerging and complex challenges of applying traditional transparency principles to the opaque world of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and automated decision-making. It dissects the specific requirements of Article 22, the "black box" dilemma, and the evolving guidance from regulators, highlighting the inherent tension between the GDPR's principle of data minimization and the data-intensive nature of modern AI.

Finally, to provide a global context for compliance, the report offers a detailed comparative analysis between the GDPR's "opt-in" transparency framework and the "opt-out" model of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). This comparison illuminates the strategic considerations for organizations operating across multiple legal jurisdictions.

The overarching conclusion is that transparency under the GDPR is a dynamic, ongoing obligation. It demands a proactive, user-focused approach that is integrated into the design of systems and processes. For organizations, embracing this mandate of clarity is not only a matter of legal compliance but a strategic imperative for managing risk, fostering trust, and ensuring the sustainable and ethical use of personal data in the digital economy.

The Foundational Principles of Transparency

The GDPR's approach to transparency is not an isolated set of rules but a principle woven into the very fabric of the regulation. It serves as the bedrock upon which the entire structure of data subject rights is built. Understanding this foundational role is critical to appreciating the gravity of the obligations and the rationale behind the specific requirements detailed in subsequent articles. Transparency is the essential conduit through which organizations demonstrate lawfulness, achieve fairness, and empower individuals.

1.1 The Triad of Data Protection: Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency

The first and arguably most important principle of the GDPR, articulated in Article 5(1)(a), establishes a foundational triad for all data processing activities. It mandates that personal data shall be: "processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject". These three elements—lawfulness, fairness, and transparency—are not independent criteria to be checked off a list; they are deeply interconnected and mutually reinforcing components of a single, overarching principle.

Lawfulness requires that every processing activity must be grounded in one of the six legal bases enumerated in Article 6 (e.g., consent, contractual necessity, legitimate interests). Furthermore, the processing must not violate any other applicable laws, whether statutory or common law. Processing data without a valid lawful basis is a fundamental breach of this principle.

Fairness acts as a crucial ethical and practical check on lawfulness. Even if a lawful basis can be identified, the processing must still be fair. In general, fairness means that data should only be handled in ways that individuals would reasonably expect, and not used in ways that have unjustified adverse effects on them. It compels an organization to consider not just whether it

can process data, but whether it should. Deceiving individuals or misleading them about how their data will be used is inherently unfair.

Transparency is the element that operationalizes fairness and substantiates lawfulness. It is the principle of being clear, open, and honest with individuals from the outset about who you are, why you are processing their personal data, and how you will use it. Without transparency, an individual cannot form a reasonable expectation of how their data will be used, making a fair assessment of the processing impossible. If processing activities are hidden from the individual, the processing is fundamentally unfair, regardless of the identified lawful basis. This linkage is vital; transparency builds the trust and confidence necessary for individuals to engage with services and, crucially, to exercise their rights under the GDPR. This is especially important in situations where individuals have a choice about entering into a relationship with an organization, as transparency allows them to make an informed decision.

The UK's Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) describes this triad as the "cornerstone of data protection law," emphasizing that organizations must satisfy all three elements. It is not sufficient to demonstrate that processing is lawful if it is fundamentally unfair to or hidden from the individuals concerned. This integrated view reveals that a failure in transparency is not a mere administrative lapse but a failure that compromises the fairness and, by extension, the lawfulness of the entire processing operation.

1.2 Deconstructing the Transparency Mandate: Recital 58 and Article 12

While Article 5 establishes the "what" of transparency, Recital 58 and Article 12 of the GDPR provide the "how." They set the specific standards for communication and create a framework for making abstract principles tangible and enforceable.

Recital 58 lays out the guiding philosophy. It explicitly states that "the principle of transparency requires that any information addressed to the public or to the data subject be concise, easily accessible and easy to understand, and that clear and plain language and, additionally, where appropriate, visualisation be used". This recital is particularly relevant in the modern digital ecosystem, where the "proliferation of actors and the technological complexity of practice" make it difficult for individuals to understand who is collecting their data and for what purpose. The emphasis on clarity and accessibility signals a deliberate move away from the long, dense, and legalistic privacy policies of the past.

Article 12 translates the philosophy of Recital 58 into binding legal obligations for the data controller. Article 12(1) requires the controller to "take appropriate measures" to provide all required information in a form that is:

Concise: Information should be presented efficiently and succinctly to avoid information fatigue.

Transparent: The meaning should be clear and open, with no hidden or ambiguous processing activities.

Intelligible: The information must be understandable to the average member of the target audience.

Easily Accessible: The data subject should not have to search extensively for the information; it should be immediately apparent where to find it.

Furthermore, the communication must use "clear and plain language". This means the information should be concrete and definitive, avoiding abstract or ambivalent terms that leave room for interpretation. The purposes of processing and the legal basis, in particular, must be unambiguous.

Article 12 also specifies the modalities for providing this information. The default method is "in writing, or by other means, including, where appropriate, by electronic means". This explicitly sanctions the use of website privacy notices. Upon request, and provided the identity of the data subject is verified, the information may also be provided orally. To further aid comprehension, Article 12(7) introduces the possibility of using standardized, machine-readable icons to give a "meaningful overview of the intended processing". Reinforcing the principle of accessibility, Article 12(5) mandates that all information and communications provided under these articles must be free of charge.

The cumulative effect of these provisions is a paradigm shift in how organizations must communicate about privacy. The burden has moved decisively from the individual's responsibility to find and decipher complex legal text to the controller's obligation to actively ensure their communications are received and understood. A privacy notice that is technically complete but practically incomprehensible to its intended audience fails to meet the standard of Article 12. The focus is on the outcome—comprehension—not merely the output of a document. This shift is further evidenced by the fact that the GDPR's structure makes transparency a prerequisite for the exercise of all other data subject rights. Articles 13 and 14 explicitly require controllers to inform individuals of their rights to access, rectify, and erase their data, among others. If this initial information is not provided in a transparent and intelligible manner, the data subject remains unaware of their ability to exercise these subsequent rights. Therefore, a failure in transparency is a systemic failure that effectively neutralizes the entire suite of protections afforded to individuals, making it a far more severe breach than a simple procedural error.

1.3 Special Considerations: Children and Vulnerable Groups

The GDPR recognizes that certain groups require specific protection, and this is explicitly reflected in its transparency requirements. Both Recital 58 and Article 12 contain provisions that heighten the standard of clarity when data processing is addressed to a child. Recital 58 states, "Given that children merit specific protection, any information and communication, where processing is addressed to a child, should be in such a clear and plain language that the child can easily understand".

This is not a suggestion but a legal requirement. It means that a standard privacy notice written for an adult audience is presumptively non-compliant if the service is also directed at children. Controllers must actively consider the cognitive development and comprehension levels of their younger users and adapt their communications accordingly. This goes beyond simply avoiding complex legal terms; it may require entirely different modes of communication. For example, guidance from data protection authorities suggests that effective methods could include the use of comics, cartoons, pictograms, animations, or other visualizations that can convey complex information in an age-appropriate manner.

This requirement underscores the GDPR's focus on meaningful communication. The test is not whether the information is technically accurate, but whether a child can genuinely understand it. This places a significant design and implementation burden on organizations that process children's data, forcing them to move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to transparency and to develop targeted, effective communication strategies for their most vulnerable users.

The Right to be Informed: A Deep Dive into Articles 13 and 14

The "right to be informed" is the practical manifestation of the transparency principle. It is codified in Articles 13 and 14, which provide detailed, prescriptive lists of the information that data controllers must provide to individuals. These articles are the cornerstone of a compliant privacy notice. They are distinguished by the context of data collection: Article 13 applies when data is collected directly from the individual, while Article 14 applies when it is obtained from another source. Adherence to these articles is not optional; it is a fundamental obligation for any organization processing personal data.

2.1 Direct Data Collection (Article 13): When You Ask for the Data

Article 13 of the GDPR specifies the information that must be provided to a data subject "at the time when personal data are obtained". This means the information must be available at the point of collection, for example, alongside a web form, at the start of a phone call, or on the first page of a paper application. Providing this information proactively ensures that the individual can make an informed decision before sharing their data.

The required information under Article 13 includes :

Identity and Contact Details: The legal name and contact details of the data controller and, where applicable, the controller's representative.

Data Protection Officer (DPO) Contact Details: If a DPO has been appointed, their contact information must be provided.

Purposes and Legal Basis: A clear explanation of why the personal data is being processed (the purposes) and the specific lawful basis under Article 6 for each purpose (e.g., consent, contract, legitimate interests). If relying on legitimate interests, those interests must be specified.

Recipients: The recipients or categories of recipients of the personal data (e.g., payment processors, cloud hosting providers, marketing partners).

International Transfers: If the controller intends to transfer personal data to a third country (outside the EEA/UK) or an international organization, this must be stated. This includes mentioning the existence of an adequacy decision or, in its absence, referencing the appropriate safeguards (e.g., Standard Contractual Clauses) and explaining how the individual can obtain a copy.

Retention Period: The period for which the personal data will be stored, or if that is not possible, the criteria used to determine that period (e.g., "for the duration of the contract plus a period of six years for legal purposes").

Data Subject Rights: The existence of the individual's rights must be clearly communicated. This includes the right to request access, rectification, erasure, restriction of processing, data portability, and the right to object to processing.

Right to Withdraw Consent: Where processing is based on consent, the individual must be informed of their right to withdraw that consent at any time, without affecting the lawfulness of processing based on consent before its withdrawal.

Right to Lodge a Complaint: The right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority (such as the ICO in the UK) must be stated.

Statutory or Contractual Requirement: The individual must be told whether the provision of their data is a statutory or contractual requirement, or a requirement necessary to enter into a contract. This includes explaining whether they are obliged to provide the data and the possible consequences of failure to do so.

Automated Decision-Making: The existence of automated decision-making, including profiling, as defined in Article 22. This requires providing "meaningful information about the logic involved, as well as the significance and the envisaged consequences of such processing for the data subject."

This comprehensive list ensures that the individual has a complete picture of the data processing lifecycle before they commit their information.

2.2 Indirect Data Collection (Article 14): When You Get Data From Elsewhere

Article 14 addresses the critical scenario of "invisible processing," where an organization obtains personal data about an individual from a source other than the individual themselves. This could involve acquiring marketing lists, using data brokers, collecting data from public sources like social media or government registries, or receiving data from a business partner. In these situations, the transparency obligation is arguably even more important, as the individual may have no idea that their data is being processed at all.

Article 14 requires the provision of most of the same information as Article 13, but with two key additions and one omission :

Addition 1: Categories of Personal Data: The controller must inform the individual of the categories of personal data concerned (e.g., "contact details, professional information, and publicly stated interests").

Addition 2: Source of the Data: The controller must specify the source from which the personal data originate and, if applicable, whether it came from publicly accessible sources.

Omission: The requirement to state whether providing the data is a statutory or contractual requirement is omitted, as this is not relevant when the data was not collected from the individual.

The timing for providing this notice is also different. The information must be provided :

Within a reasonable period after obtaining the data, and at the latest within one month.

If the data is to be used for communication with the data subject, at the latest at the time of the first communication.

If a disclosure to another recipient is envisaged, at the latest when the data is first disclosed.

Article 14(5) provides for limited exceptions to this notification requirement, such as if the data subject already has the information, if providing it proves impossible or would involve a "disproportionate effort," or where obtaining or disclosing the data is laid down by law. However, the "disproportionate effort" exemption is interpreted very narrowly by regulators. It is not a loophole to be used for convenience or to avoid cost. A controller claiming this exemption must balance the effort required against the impact on the individual's rights. Given the importance of notifying individuals about invisible processing, the bar for this exemption is extremely high. It is typically reserved for situations like processing for archival or research purposes involving vast historical datasets where contact details are unavailable, and even then, the controller must take alternative measures, such as making the information publicly available. In most commercial data-sharing scenarios, the exemption will not apply.

2.3 Comparative Information Requirements (Articles 13 & 14)

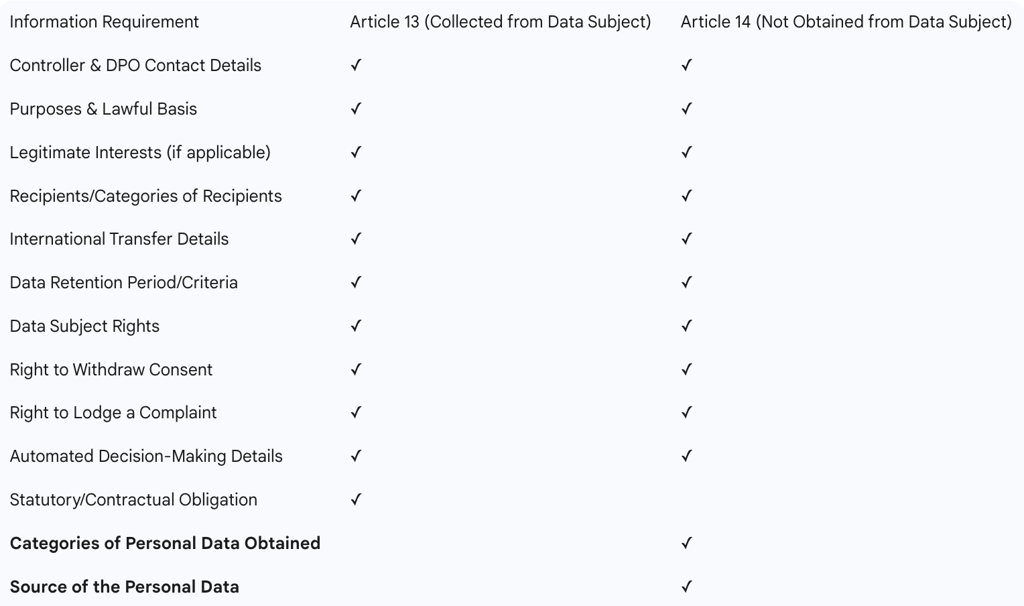

For compliance professionals managing diverse data intake channels, understanding the precise differences between Article 13 and Article 14 disclosures is a critical operational task. An organization may collect data directly via a website sign-up form (triggering Article 13) while simultaneously acquiring a prospect list from a third-party data provider (triggering Article 14). Deploying the correct privacy information in each context is essential to avoid compliance gaps. The following table serves as a quick-reference tool to highlight these key distinctions.

This side-by-side comparison makes the operational requirements clear. For indirectly collected data, the focus shifts to informing the individual about what kind of data has been obtained about them and from where, while the question of their obligation to provide it becomes irrelevant.

From Law to Document: Crafting the GDPR-Compliant Privacy Policy

Translating the dense legal requirements of the GDPR into a clear, compliant, and user-friendly document is a critical task for any data controller. This document, most accurately termed a "Privacy Notice" in the context of external communication, is the primary vehicle for fulfilling the transparency obligations of Articles 12, 13, and 14. Its creation is not merely a legal drafting exercise but a multidisciplinary effort that involves legal, communications, and user experience considerations.

While the terms "Privacy Policy" and "Privacy Notice" are often used interchangeably, a useful distinction exists. A "Privacy Notice" is the external-facing statement provided to data subjects to fulfill the information requirements of Articles 13 and 14. A "Data Protection Policy," by contrast, is typically an internal document that sets out an organization's rules and procedures for its staff on how to handle personal data. Using the precise terminology of "Privacy Notice" for external documents can signal a more mature and granular understanding of the GDPR framework.

3.1 Anatomy of a Privacy Policy

A robust, GDPR-compliant privacy notice must be structured to include all the legally mandated elements in a logical and accessible manner. Each section should map directly back to the requirements of Articles 13 and 14, providing a comprehensive picture of the organization's data processing activities. The essential clauses include:

Who We Are / Controller Information: This section must clearly identify the data controller by its legal name and provide comprehensive contact details, such as a physical address, email, and phone number. If applicable, the contact details for the EU/UK representative and the Data Protection Officer (DPO) must also be included.

The Personal Data We Collect: This clause should detail the specific categories of personal data the organization processes. Examples include contact information, payment details, usage data, location information, cookies, and IP addresses. The level of detail should be sufficient for the individual to understand what information is held about them.

How We Use Your Personal Data (Purposes and Lawful Basis): This is one of the most critical sections. For each distinct processing purpose (e.g., fulfilling an order, sending marketing emails, personalizing website content), the notice must clearly state the purpose and the specific lawful basis relied upon for that purpose (e.g., performance of a contract, consent, legitimate interests). If legitimate interests are used, those interests must be explained.

Who We Share Your Data With: The notice must identify the recipients or categories of recipients with whom personal data is shared. This includes third-party service providers (processors) like cloud storage services, payment gateways, and analytics platforms, as well as any other third-party controllers.

International Data Transfers: If personal data is transferred outside the European Economic Area (EEA) or the UK, this section must explain this fact. It must also describe the legal safeguards in place to protect the data, such as an adequacy decision or the use of Standard Contractual Clauses, and inform individuals how they can access a copy of these safeguards.

How Long We Keep Your Data (Data Retention): The notice must state the specific period for which data will be stored. If a precise period is not possible, it must outline the criteria used to determine the retention period (e.g., "data will be retained for the duration of the client relationship plus any period required by tax law").

Your Data Protection Rights: This section must clearly enumerate the eight rights afforded to data subjects under the GDPR: the right to be informed, the right of access, the right to rectification, the right to erasure, the right to restrict processing, the right to data portability, the right to object, and rights in relation to automated decision making and profiling. Crucially, it must also provide clear instructions on how individuals can exercise these rights.

Cookies and Other Tracking Technologies: The notice should disclose the use of cookies and similar technologies, explaining their purpose (e.g., for functionality, analytics, advertising) and linking to a more detailed cookie policy or consent management tool.

Changes to This Privacy Notice: It is best practice to include a clause explaining how the organization will inform users of any material changes to its privacy practices.

3.2 Drafting for Clarity: Best Practices and Modern Approaches

Merely including the required clauses is insufficient; the presentation of the information is equally critical for compliance with Article 12. The GDPR mandates a move away from dense, impenetrable legal text towards clear, user-centric communication.

The Plain Language Imperative: To be "intelligible" and use "clear and plain language," a privacy notice should adhere to simple drafting principles. This includes using the active voice ("We use your data to...") instead of the passive voice ("Your data is used to..."), employing short sentences and paragraphs, and using bullet points to break up long lists. Vague and conditional language, such as "we may," "might," "often," or "some," should be avoided in favor of concrete and definitive statements. Legal and technical jargon should be eliminated or, if unavoidable, clearly explained.

Beyond the Wall of Text: Modern Delivery Techniques: Recognizing the challenge of conveying extensive information without causing "information fatigue" , supervisory authorities like the ICO actively endorse modern, dynamic methods for delivering privacy information. These techniques treat the privacy notice as a communication challenge to be solved with good design, not just a legal document to be published.

Layered Notices: This is perhaps the most widely recommended approach. It involves presenting a short, high-level summary of the key privacy information (e.g., in a pop-up or a dedicated "highlights" section) with clearly signposted links to a more detailed, comprehensive notice. This allows users to get the essential information quickly while providing an easy path to a deeper dive if they choose, resolving the tension between completeness and comprehension.

Just-in-Time Notices: Instead of presenting all information at once, this technique provides specific, context-relevant information at the point of data collection. For example, a small pop-up next to a field asking for a phone number could explain, "We need this to send you delivery updates by SMS". This enhances transparency at the most relevant moment.

Dashboards and Preference Centers: These are interactive tools that go beyond passive information delivery. A privacy dashboard can show an individual exactly what data is held about them, how it is being used, and provide them with granular controls to manage their preferences or withdraw consent. This approach directly empowers users, turning the notice into an active control panel.

Validating Effectiveness: Transparency is not a one-time task. Organizations must regularly review their privacy notices to ensure they remain accurate and reflect current processing activities. Furthermore, to truly meet the "easy to understand" standard, it is best practice to conduct user testing. This involves getting feedback from members of the target audience on the clarity and accessibility of the privacy information, allowing the organization to refine its approach based on real-world comprehension rather than assumptions.

By adopting these practices, organizations can transform their privacy notice from a perceived legal burden into a valuable asset for user experience (UX) and customer experience (CX). The principles of good privacy communication—clarity, accessibility, and user control—are fundamentally principles of good design. An organization that invests in the UX of its privacy communications is not only more likely to achieve compliance but is also demonstrating respect for its users, which builds the trust that is essential for long-term customer relationships. This reframes the compliance budget for privacy as a strategic investment in CX and brand reputation.

The Cost of Obscurity: Enforcement and Sanctions

The GDPR's transparency requirements are not merely advisory; they are backed by a robust enforcement regime with the power to impose significant financial penalties. Supervisory authorities across Europe are tasked with upholding these obligations, and a review of their enforcement actions reveals that failures in transparency are a primary trigger for investigation and sanctions. Understanding this enforcement landscape is crucial for organizations to accurately assess the risks associated with non-compliance and to prioritize their compliance efforts accordingly.

4.1 The Role of the Supervisory Authority

Each EU member state has an independent public authority, known as a Supervisory Authority (SA), responsible for monitoring and enforcing the application of the GDPR. In the UK, this role is filled by the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO). These authorities have a broad mandate that includes providing guidance to organizations, promoting good practice, investigating complaints from the public, and taking corrective action when breaches of the law are identified.

Their enforcement powers are extensive and include :

Warnings and Reprimands: For less severe infringements, an SA can issue an official warning or reprimand.

Corrective Orders: SAs can order a controller or processor to bring their processing operations into compliance, for example, by ordering them to provide the required information to data subjects or to erase data unlawfully processed.

Limitations or Bans on Processing: In serious cases, an SA can impose a temporary or permanent ban on specific processing activities.

Administrative Fines: The most well-known power is the ability to levy substantial administrative fines.

The ICO's strategic plan, known as ICO25, explicitly identifies promoting "openness, transparency and accountability" as a key objective. This signals that transparency is a high priority for regulatory scrutiny. While the ICO often states a preference for working with organizations to achieve compliance through guidance and improvement plans , it has demonstrated a willingness to use its full range of powers when necessary. A recent strategic shift involves the ICO publishing all reprimands it issues, not just those accompanied by fines. This move is intended to increase the transparency of the enforcement process itself, providing lessons for other organizations and holding non-compliant entities publicly accountable. However, this approach has also drawn criticism, with some arguing that a focus on advice over enforcement orders can lead to a perception of the ICO as a "regulator in name only," allowing non-compliance to persist.

4.2 Analysis of Landmark Fines for Transparency Failures

The GDPR establishes two tiers of administrative fines. Less severe violations can result in fines of up to €10 million or 2% of the company's total global annual turnover, whichever is higher. More severe violations, including breaches of the core principles in Article 5 (such as transparency), can lead to fines of up to €20 million or 4% of global turnover. The use of global turnover means that for large multinational corporations, the potential penalties are immense.

An analysis of the most significant fines issued under the GDPR reveals a clear and consistent pattern: regulators are not primarily penalizing organizations for minor, clerical errors in their privacy notices. Instead, the largest fines target fundamental, business-model-level failures in transparency. These are cases where a lack of clarity is strategically employed to obscure the true purpose and legal basis of data processing, particularly in the context of behavioral advertising and large-scale data monetization.

Google (€50 million, CNIL, 2019): France's supervisory authority fined Google for a "lack of transparency, inadequate information and lack of valid consent regarding the ads personalisation". The CNIL found that essential information, such as the purposes of processing and data retention periods, was spread across multiple documents, requiring users to take several steps to access it. This violated the principles of accessibility and clarity. Crucially, the lack of transparency meant that the consent obtained from users was not sufficiently informed and therefore invalid.

Meta (Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp) (Multiple Fines, DPC): The Irish Data Protection Commission has issued several large fines against Meta's various platforms. A €405 million fine against Instagram related to the processing of children's data, where children's accounts were made public by default and business accounts for children publicly displayed their contact information—a clear failure of transparency and fairness. A €390 million fine concerned the legal basis for advertising on Facebook and Instagram. Meta had claimed that processing user data for personalized ads was necessary for the "performance of a contract," a legal basis that does not allow users to object. Regulators found this to be a non-transparent attempt to bypass the need for consent, forcing users to accept advertising as a condition of using the service.

Amazon (€746 million, CNPD, 2021): Luxembourg's authority issued this record-breaking fine because Amazon's advertising targeting system processed personal data without valid, "freely given" consent. The underlying issue was a failure to transparently provide users with a clear choice regarding the use of advertising cookies.

La Liga (€250,000, AEPD, 2019): Spain's football league was fined for a feature in its mobile app that used the device's microphone to listen for broadcasts of matches, in order to identify bars that were showing games illegally. This purpose was not clearly and adequately explained to users, representing a form of unexpected and non-transparent processing.

These cases demonstrate that the highest regulatory risk lies where transparency failures are systemic and directly enable legally questionable data processing at scale. While all the information requirements of Articles 13 and 14 are legally binding, enforcement actions suggest that supervisory authorities place the greatest emphasis on transparency regarding three core areas: (1) the lawful basis for processing, (2) the purposes of processing, and (3) the rights of the data subject. Failures in these areas are most likely to be perceived as fundamentally undermining an individual's control over their personal data, and thus, are most likely to attract the most severe sanctions.

The Algorithmic Challenge: Transparency in an Age of AI

The principles of transparency, designed for a world of structured databases and clear processing flows, face unprecedented challenges when applied to the complex, dynamic, and often opaque systems of Artificial Intelligence (AI). As organizations increasingly deploy AI for everything from product recommendations to critical decisions in hiring, credit, and healthcare, ensuring compliance with the GDPR's transparency mandate has become a leading-edge legal and technical problem. The regulation contains specific provisions for automated decision-making, but their application to modern machine learning models presents significant hurdles.

5.1 Automated Decision-Making Under Article 22

The GDPR directly anticipates the risks of automated systems in Article 22, which establishes a conditional prohibition on certain types of AI-driven decisions. Article 22(1) grants the data subject the right "not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her".

Key elements of this provision are:

"Solely automated": The decision must be made without any meaningful human involvement. If a human reviews the output of an algorithm and has the authority and competence to change the decision, it may not be considered "solely" automated.

"Legal or similarly significant effects": A legal effect could be the denial of a social benefit or the cancellation of a contract. A "similarly significant" effect is less defined but would include outcomes like the automatic refusal of an online credit application or rejection in an automated e-recruiting process.

This prohibition is not absolute. Such processing is permitted under three conditions :

It is necessary for entering into or performing a contract between the individual and the controller.

It is authorized by Union or Member State law.

It is based on the individual's explicit consent.

Even when permitted, the controller must implement crucial safeguards to protect the individual. These include, at a minimum, the right for the individual to obtain human intervention, to express their point of view, and to contest the decision.

5.2 The "Black Box" Dilemma and the Right to Explanation

The greatest challenge to AI transparency is the "black box" problem. Many advanced AI models, particularly those based on deep learning and neural networks, operate in ways that are inscrutable even to their creators. The complex interplay of millions of parameters makes it practically impossible to trace a specific output back to a clear, human-understandable chain of logic. This inherent opacity is in direct conflict with the GDPR's transparency requirements.

Under Articles 13, 14, and 15, when automated decision-making is used, controllers must provide individuals with "meaningful information about the logic involved, as well as the significance and the envisaged consequences of such processing". This has led to extensive debate about a so-called "right to explanation" under the GDPR.

While the text does not grant an absolute right to a complete technical explanation of an algorithm's inner workings, it does establish a right to understand the rationale behind a specific decision that affects the individual. This is where the practical interpretation of "meaningful information" becomes critical. Given the technical impossibility of explaining the precise weighting within a neural network, the regulatory expectation is evolving. "Meaningful information" is increasingly understood to mean providing clarity on the more practical elements of the decision-making process. This includes being transparent about:

The data used to train the model and the key data points used as inputs for a specific decision.

The main factors or criteria that the model is designed to assess.

The overall purpose and intended logic of the system.

The potential significance and consequences for the individual.

The mechanisms available to challenge the outcome and secure a human review.

This pragmatic approach shifts the focus from explaining the complex how of the algorithm's internal state to the more actionable what (what data is used) and why (what factors are considered), which empowers the individual to effectively contest a decision. This is where the field of Explainable AI (XAI) becomes a vital compliance tool, providing techniques to generate simplified, user-friendly explanations for model outputs, such as, "Your loan application was denied due to a high debt-to-income ratio and a low credit score".

5.3 Evolving Regulatory Stance: ICO and EDPB Guidance

Supervisory authorities are actively working to provide guidance on this complex issue. The ICO has adopted a risk-based approach, emphasizing that organizations must conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) for high-risk AI processing. The ICO's guidance stresses the importance of fairness, accountability, and mitigating bias throughout the entire AI lifecycle, from data collection for training to model deployment. The ICO provides resources like the "AI and Data Protection Risk Toolkit" to help organizations assess and manage these risks.

Recent consultations by the ICO on generative AI have highlighted the significant challenges posed by web scraping for training data. The ICO's preliminary view is that "legitimate interests" is likely the only viable lawful basis for such large-scale data collection, but meeting the three-part test (purpose, necessity, and balancing) is a high hurdle. Crucially, the ICO has stated that robust transparency is essential to pass the balancing test, as individuals cannot exercise their rights if they are unaware that their data is being processed. A lack of transparency in this area is a significant compliance risk and a likely target for future enforcement.

This entire domain is complicated by a fundamental conflict of principles within the GDPR itself. The principle of data minimization (Article 5(1)(c))—requiring that data be adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary—is often at odds with the operational reality of AI, which frequently relies on data maximization for effective training. This tension forces organizations into a difficult position, requiring them either to limit the efficacy of their models, invest heavily in privacy-preserving techniques like anonymization or synthetic data, or construct an exceptionally robust legitimate interests assessment to justify the large-scale processing. In all cases, transparency becomes the critical tool for explaining and defending these choices to both individuals and regulators.

Finally, the forthcoming EU AI Act will work in tandem with the GDPR. It introduces its own risk-based framework with specific and stringent transparency obligations for systems deemed "high-risk," such as providing users with clear instructions for use and ensuring human oversight capabilities. This dual regulatory landscape will require organizations to navigate an even more complex set of transparency requirements in the near future.

A Global Perspective: Comparing GDPR and CCPA/CPRA Transparency

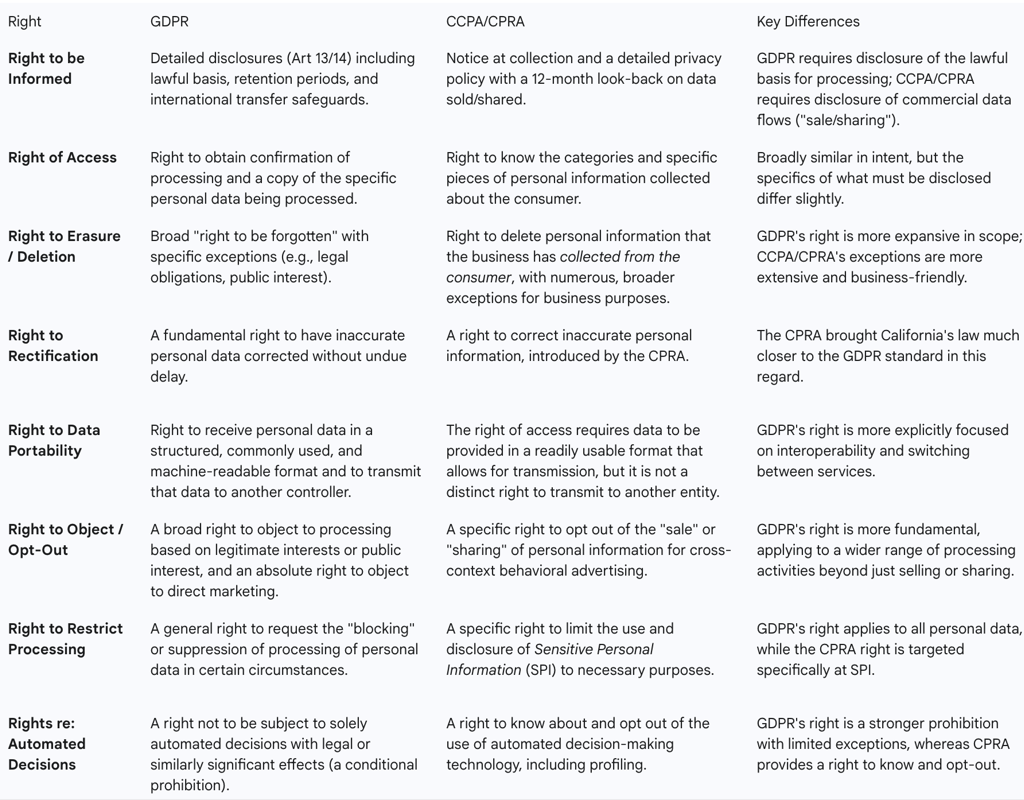

For organizations operating on a global scale, compliance cannot be viewed through the lens of a single regulation. It requires a nuanced understanding of the world's major privacy laws and the development of a flexible framework that can accommodate their differences. The most significant point of comparison for the GDPR is the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), as amended and expanded by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). While both frameworks aim to enhance individual privacy, their foundational philosophies, scope, and specific transparency requirements diverge in critical ways.

6.1 Divergent Philosophies: "Opt-In" vs. "Opt-Out"

The most fundamental difference between the GDPR and the CCPA/CPRA lies in their approach to permission for data processing. This philosophical divergence shapes nearly every aspect of their respective transparency obligations.

GDPR's "Opt-In" Framework: The GDPR operates on a principle of "privacy by default". Before an organization can lawfully process personal data, it must proactively establish a valid legal basis from the six options listed in Article 6. When that basis is consent, it must be a "freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous" affirmative action—an opt-in. This means processing is prohibited by default and only becomes permissible once a legal justification is established. Transparency, in this context, is about informing the individual of this legal basis

before processing begins.

CCPA/CPRA's "Opt-Out" Framework: In contrast, the CCPA/CPRA is primarily an "opt-out" regime. It generally permits businesses to collect and process personal information by default. The law then grants consumers specific rights to control that data, most notably the right to opt out of the "sale" or "sharing" of their personal information. The transparency obligation here is focused on making consumers aware of this right to opt out and providing them with clear and accessible mechanisms to exercise it.

This core difference has profound practical implications. Under GDPR, the privacy notice must explain the justification for processing. Under CCPA/CPRA, the notice must explain how to stop certain types of processing.

6.2 Notice and Disclosure Requirements

These differing philosophies translate into distinct requirements for what must be included in a privacy notice.

GDPR Requirements: As detailed in Part II, a GDPR notice must be comprehensive, covering the entire data lifecycle. Key disclosures that are unique to or more stringent under GDPR include:

Lawful Basis: The specific legal basis must be declared for each and every processing purpose. This has no direct equivalent in the CCPA/CPRA.

Data Retention: The notice must state either a specific retention period or the criteria used to determine it.

International Transfers: Detailed information about transfers outside the EEA/UK and the safeguards in place is mandatory.

Data Subject Rights: The notice must list all eight data subject rights under the GDPR.

CCPA/CPRA Requirements: The CCPA/CPRA mandates a "notice at collection" and a more detailed privacy policy. Its unique disclosure requirements are more focused on commercial data flows:

12-Month Look-Back: The privacy policy must be updated at least annually and disclose the categories of personal information the business has collected, sold, and shared over the preceding 12 months.

Specific Opt-Out Links: Businesses must provide conspicuous links on their homepage, such as "Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information" and "Limit the Use of My Sensitive Personal Information". These are prescriptive requirements with no GDPR parallel.

Categories of Information: The notice must list the categories of personal information and sensitive personal information it collects and the purposes for their use.

"Household" Data: A unique feature of the CCPA/CPRA is that its definition of personal information can extend to data that identifies a "household". This creates a transparency obligation not present in the GDPR, which focuses exclusively on the "natural person." A privacy notice for California must therefore consider how to explain the collection of data linked to a shared device or network and how rights might be exercised on behalf of a household.

6.3 Comparative Data Subject/Consumer Rights

A core component of transparency is informing individuals of their rights. While many of the rights under GDPR and CCPA/CPRA appear similar in name, their scope and application differ significantly. A global organization must build a rights-response workflow that can accommodate these nuances.

For global organizations, the generally stricter and more comprehensive nature of the GDPR often leads to it becoming the de facto baseline for their global privacy program. It is frequently more efficient to design a core transparency framework that meets the high standards of the GDPR (e.g., identifying a lawful basis for all processing, providing detailed retention information) and then add the specific, prescriptive elements required by other jurisdictions like California (e.g., the "Do Not Sell or Share" link and the 12-month look-back). In this way, the GDPR's robust transparency mandate sets a high-water mark that shapes global compliance practices.

Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

The General Data Protection Regulation has firmly established transparency as a foundational principle of modern data protection law. It is not a passive, check-the-box exercise in legal drafting but a dynamic, ongoing obligation that demands clarity, accessibility, and honesty in all communications with individuals about their personal data. This report has demonstrated that transparency is the essential mechanism through which the principles of lawfulness and fairness are realized, and it is the gateway that empowers individuals to exercise their full suite of data subject rights.

The analysis of the legal framework, from the core principles of Article 5 to the specific disclosure mandates of Articles 13 and 14, reveals a clear legislative intent: to shift the burden of comprehension from the individual to the data controller. The endorsement of user-centric communication techniques—such as plain language, layered notices, and interactive dashboards—by supervisory authorities underscores that compliance is measured by the effectiveness of the communication, not merely its existence.

The significant financial penalties levied for transparency failures send an unequivocal message. Regulators are targeting systemic and strategic obfuscation, particularly where a lack of clarity is used to obscure the legal basis for processing personal data for commercial gain. This elevates the privacy notice from a simple legal document to a high-stakes declaration of an organization's data practices and a key area of regulatory risk.

Emerging technologies, especially Artificial Intelligence, present the most profound challenge to this mandate of clarity. The "black box" nature of complex algorithms and the data-intensive requirements of machine learning create a direct tension with core GDPR principles like transparency and data minimization. Navigating this landscape requires a sophisticated, risk-based approach, a commitment to developing explainable systems, and a pragmatic focus on providing meaningful information about the inputs, core logic, and outcomes of automated decisions.

For organizations operating globally, the GDPR often serves as the de facto standard for transparency, with the more prescriptive but philosophically different requirements of frameworks like the CCPA/CPRA layered on top. This necessitates a flexible yet robust global compliance program that can accommodate jurisdictional nuances while adhering to a high baseline of data protection.

Ultimately, embracing the GDPR's mandate of clarity is more than a legal necessity; it is a strategic imperative. Organizations that successfully integrate transparency into their culture and operations will not only mitigate significant legal and financial risks but will also build the user trust that is the essential currency of the modern digital economy.

Strategic Recommendations for Compliance Professionals

Conduct Regular Transparency Audits: Treat the privacy notice and all related communications as living documents. Schedule, at a minimum, an annual review to ensure all disclosures are accurate, complete, and reflect current data processing activities, including new third-party vendors, purposes, or data types.

Integrate Transparency into the Design Lifecycle (Privacy by Design): Embed privacy notice considerations into the product and service development process. When a new feature is designed that collects personal data, the "just-in-time" notice and updates to the main privacy notice should be part of the project plan, not an afterthought.

Adopt a User-Centric (UX) Approach to Communication: Move beyond a single, static "wall of text." Implement a layered notice strategy as the default. Collaborate with UX/UI design and communications teams to test the clarity and accessibility of privacy information with real users.

Prioritize Clarity on the "Big Three": While all disclosure requirements are important, focus the most intense scrutiny on ensuring absolute clarity and accuracy regarding the lawful basis for processing, the purposes of processing, and the clear enumeration of data subject rights and how to exercise them. These are the areas of highest regulatory risk.

Develop a Governance Framework for AI Transparency: For any system that uses AI or automated decision-making, create a specific governance protocol. This should include conducting a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA), documenting the logic and key factors of the model, and establishing a clear process for human intervention and for responding to challenges from individuals, as required by Article 22.

Establish a Unified Global Rights Response Mechanism: For multinational organizations, create a centralized workflow for handling data subject and consumer rights requests. This system should be sophisticated enough to apply the correct legal standard (GDPR, CCPA/CPRA, etc.) based on the individual's residency, ensuring that response timelines, scope, and exceptions are handled correctly for each jurisdiction.

Maintain Historical Records: Keep a version-controlled log of all past privacy notices and the dates they were active. This is a critical component of the accountability principle, enabling the organization to demonstrate what information was provided to an individual at a specific point in time.

The intersection of privacy policies and transparency under GDPR represents more than a regulatory compliance exercise—it marks a fundamental shift in how organizations communicate with individuals about data practices. As we've explored throughout this article, GDPR has transformed privacy policies from obscure legal disclaimers into essential tools for meaningful transparency and trust-building. This evolution reflects broader changes in societal expectations about data privacy and the growing recognition that effective transparency serves both ethical and business imperatives.

The journey toward truly transparent privacy communication continues to evolve. Organizations face ongoing challenges in balancing comprehensive disclosure with accessible communication, adapting to diverse user needs across channels, and keeping pace with regulatory interpretations and enforcement priorities. However, those that embrace these challenges as opportunities for innovation often discover that transparency can become a powerful differentiator and competitive advantage in increasingly privacy-conscious markets.

As navigating GDPR compliance in the AI era becomes increasingly complex, transparency will remain an essential bridge between technical compliance and meaningful user empowerment. Organizations that approach transparency not as a regulatory burden but as an opportunity to demonstrate values, build trust, and engage users will be best positioned to thrive in this evolving landscape.

The most successful organizations recognize that true transparency goes beyond careful wording in a privacy policy—it reflects a genuine commitment to respecting individual privacy and communicating honestly about data practices. By embracing this broader understanding of transparency, companies can not only meet their GDPR obligations but contribute to a digital ecosystem where privacy is protected, trust is preserved, and innovation flourishes on a foundation of genuine informed choice.

FAQ Section

What are the key components of a GDPR-compliant privacy policy?

A GDPR-compliant privacy policy must include the identity and contact details of the data controller, purposes and legal bases for processing, data retention periods, categories of personal data collected, recipients of the data, information about data subject rights, details on international transfers, and the right to lodge complaints with supervisory authorities.

How often should privacy policies be updated under GDPR?

Privacy policies should be reviewed and updated whenever there are significant changes to data processing activities, at least annually as part of regular compliance reviews, and in response to new regulatory guidance or relevant court decisions.

What reading level should a GDPR-compliant privacy policy target?

GDPR requires privacy policies to use clear and plain language that is understandable by the average person. Aim for a high school reading level (Flesch Reading Ease score of 60-70) to ensure accessibility while conveying necessary information.

How can businesses measure the effectiveness of their privacy policies?

Businesses can measure privacy policy effectiveness through readability scores, user comprehension testing, bounce rates on privacy pages, completion rates for consent flows, and tracking the volume of privacy-related inquiries and complaints.

Can a privacy policy be too transparent under GDPR?

While GDPR encourages comprehensive transparency, overwhelming users with excessive information can reduce comprehension and effectiveness. Use layered notices that provide essential information upfront with more details available for those who want it.

What are the consequences of having an inadequate privacy policy under GDPR?

Consequences include regulatory fines up to €20 million or 4% of global annual turnover, enforcement actions requiring policy changes, reputation damage, loss of customer trust, and potential civil litigation from affected individuals.

How should privacy policies address automated decision-making and profiling?

Privacy policies must disclose when automated decision-making or profiling occurs, explain the logic involved in simple terms, outline the significance and potential consequences for individuals, and inform users of their right to object to such processing.

Are cookie banners required as part of GDPR transparency requirements?

While not explicitly required by GDPR, cookie banners have become a common method for obtaining consent for non-essential cookies, which is required under both GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive when using cookies for tracking or marketing purposes.

How can small businesses implement GDPR-compliant privacy policies without extensive resources?

Small businesses can focus on simplicity and clarity, use available templates from supervisory authorities as starting points, leverage privacy policy generators with customization options, and conduct a focused data inventory to ensure all processing activities are accurately reflected.

What role do Data Protection Impact Assessments play in privacy policy development?

Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) help identify risks in data processing activities, providing valuable input for privacy policies by ensuring all high-risk processing is transparently disclosed and appropriate safeguards are communicated to data subjects.

Additional Resources

EU GDPR: A Comprehensive Guide - An in-depth exploration of GDPR principles, requirements, and implementation strategies.

Privacy by Design: A Guide to Implementation Under GDPR - Practical approaches to embedding privacy considerations throughout the development lifecycle.

Balancing Data Protection and Innovation Under GDPR - Strategies for maintaining compliance while enabling data-driven business innovation.

The Accountability Principle in GDPR: Enhancing Data Protection and Business Practices - Understanding how transparency connects to broader accountability obligations.

GDPR Enforcement Trends and Notable Cases - Analysis of regulatory enforcement priorities and significant transparency-related cases.